Max is ready.

Thirty seconds after the text appears on my phone, Max B is on the line. His voice still has the nasally, gruff charisma you can hear on songs like “Never Wanna Go Back” and “Why You Do That.” Remember, this is a man who’s rapped he could find Osama Bin Laden in a New York City corner store, a man who compared his dick to a “Chevy with a V-10 engine sitting on 20-inch Pirellis.”

But while the voice of the East Jersey State Prison inmate on the line is unmistakably Max B, it doesn’t sound like Max B. His tone is measured, his delivery less menacing. Max B is on the phone, but Charly Wingate, a 42-year-old Black man, who has spent the last quarter of his life in prison, is speaking. And he’s ready to come home.

Over the last decade, his following has grown from a cult to a culture. During his 15-year career, the months in which people Googled his name most all happened while he was incarcerated. Max knows he’s loved, but he doesn’t feel it.

When that is exactly is unclear; last year he told the world that a 75-year prison sentence from his involvement in a deadly 2009 robbery had been reduced to 12 years, which would peg his release sometime in 2021. ”I will be leaving earlier than my original date that’s on paper, but I’m taking it one day at a time,” Max says.

Wingate went into prison a man but will reenter the world as a myth. Over the last decade, his following has grown from a cult to a culture. His name has been invoked to contextualize slang and title other rappers’ songs. During his 15-year career, the months in which people Googled his name most all happened while he was incarcerated. Max knows he’s loved, but he doesn’t feel it. “I can’t really see it from inside here,” he says. “You never really feel what’s going on until you’re out there in the flesh. It’s difficult to see the impact my music has outside.”

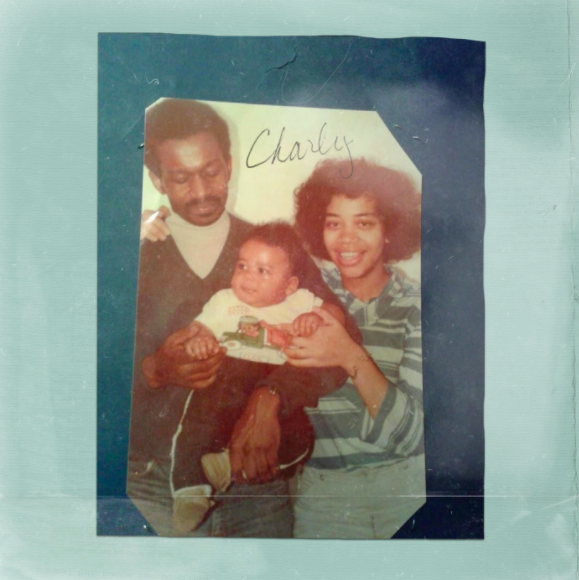

He plans to release a new EP, Charly, featuring what the usually brash MC describes as the most mature music of his career. On the Dame Grease-produced first single “Goodman,” which dropped in late May, Max proclaims he’s leaving the streets alone and his soul is saved. “These Devils are White as cotton,” he argues, “Jesus is Black as fuck.” The artwork for the single is a picture of baby Max being held by his parents.

Prison leaves inmates alone with their thoughts, but incarceration’s crushing psychological effects inhibit creative output. Meek Mill didn’t write a single song during his last prison stint because of depression and stress. 2Pac, a man who recorded 13 tracks in his first four days out of prison in 1996, only wrote one song in prison — and wrote about his battle with depression while incarcerated. Rap personas are products of the imagination, and the depressive influences of prison are enough to put the persona in a coma.

Luckily for Max B loyalists, Wingate was able to keep Max alive. The wavy wizard claims he has countless verses written in prison. But, he says, he only got to that point after finding a slice of normalcy for himself — and letting his mind transcend confinement.

“I have a regimen now,” he explains. “I wake up in the morning and do all types of other stuff: Go work out, eat. I spend a few hours writing these days. I have to use imagination now, but it wasn’t that hard to find inspiration.”

Unfortunately for him and millions of other prisoners across the United States, they can be the victims of freedom without also being recipients. Wingate has spent the last three or so years at the East Jersey State Prison in New Jersey, a state that at the end of May had as many prisoner Covid-19 casualties (43) as New York, Illinois, and Louisiana combined. He saw the humans behind those numbers a few months ago when “everybody was kinda sick” in his prison, including Wingate himself.

“I had a few symptoms a few months ago, but I’m good now,” he says. “The facility tested everybody and is separating everybody now. We’re staying low and staying clean. We’re wiping everything down. Even though we’re so close to each other, we’re still practicing social distancing. We try to make it work.” There’s no anxiety or exasperation in his voice; he speaks like a man prepared to deal with anything because he was born not expecting to go through anything less.

When he’s released in 2021, the 42-year-old rapper will have spent close to half of his life without freedom: eight years in prison for robbery (1997–2005), and more than a decade for the 2006 hotel robbery that led to him being behind bars since 2009. “I ain’t scared of the world,” he says. “The world needs to be scared of me.”

There’s little reason not to believe him. The last time he returned from jail in July 2007, he gave hip-hop one of the most prolific runs in recent memory. In two years of being a free man, Max B released more than 10 mixtapes and recorded a wave of verses. His etched his persona in people’s minds: dark shades, a wide smile, a laugh that grated the ears into submission. “I was excited,” he says of that fertile period. “I [served my full prison sentence], so I didn’t really have any parole. I was able to move around to do what I needed to do. I was in a happy place when I was recording.”

Yet, the world has changed in fundamental ways since he went inside. Music streaming services have replaced album sales, turning touring and appearances into lifeblood for many artists. More songs break big on TikTok than radio. And with Covid-19 upending everything from travel to recreational spending, the state of the world itself is in question. That’s a lot to navigate for any artist, let alone one who’s been out of the public eye.

Yet, what’s got him excited to come home isn’t being able to binge a Netflix show—it’s the prospect of being able to record the way he used to. “I miss the actual studio,” he says. “I could lay everything down and get up out of there. There’s a lot of new stuff out there, a lot of new setups.”

While no details on the terms of Max’s upcoming release have been made publicly available, he more than likely will be on parole — requiring him to check-in with a parole officer who has to approve his travel and deem if he should remain free. Max will be free when he’s released, but the Max B of old may not return to the public when Charly Wingate does.

For him, that’s the whole point. “Now, they get a chance to see the new me and the new quality,” he says. “It’s a beautiful thing, what we doing here. It’s unprecedented. It’s uncanny. It’s never been done.” After he’s released, he says, the music he’s been writing will be too.

There will still be signs of vintage Max when Wingate returns; the linguistic mastery that a generation of rappers have co-opted and followed over the last decade didn’t dull in prison. “I got ‘Don Snow’ concepts I’m coming up with,” he says. “King of the North. It’s that new stiley.” This last part, pronounced “still-lay,” is his newest coinage. “That’s my shit,” he says. “Tell everybody to not steal my shit.”

As the call winds down and Max’s return plans become clearer, Charly Wingate has one final message to give to the outside world: “I love y’all,” he says. “Stay safe. I appreciate y’all for supporting my music. A lot of pieces have to go into play for this thing to work, so keep that in mind. I’m working hard, and I’m coming out there to be the best man I can be for y’all.”

Max is ready.