In March, when Dr. Kameno Bell saw a patient come out of an ambulance and into his emergency room, he did a double take because the man looked so much like him. Black man, same build, about the same age as Dr. Bell — and all he could manage to say was that he couldn’t breathe. An emergency room doctor solves mysteries every single shift, so Bell looked the man over, noted no immediate signs of injury, and got ready to figure it out.

Before he could wash his hands, the man was dead.

“Listen,” Bell says now. “I work in an emergency room, we see death. I know how to manage it. But this man? I was looking at myself. And I couldn’t believe how fast it happened. That could have been me.”

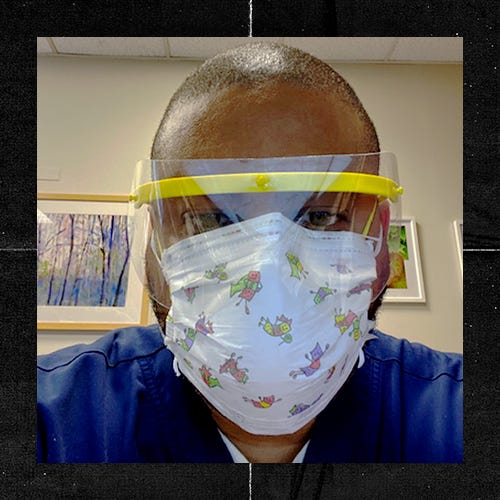

That was the moment Bell started searching for PPE and suiting up properly. Nine months later, like so many other Black doctors and nurses on the frontlines, he’s still grabbing his PPE — and he’s prepared to see this pandemic through.

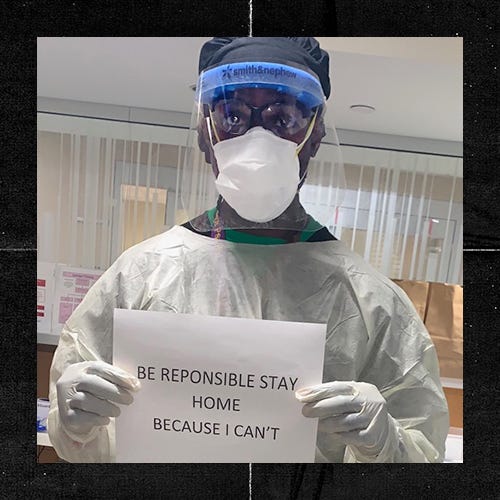

2020 will go down in history in a million different ways. Our health care system was stretched to the breaking point. Racial disparities in healthcare at large hurtled out of the shadows and into view. Health care workers nationwide had to learn about Covid-19, protect themselves and their families, and save lives — an inexorably mounting number of lives — every day.

In March, there just wasn’t enough information about how Covid-19 spread, how it affected people, or how to treat it. Dr. Patrik Charles, an ER doctor in Northern New Jersey, realized early on that the doctors in his hospital were going to have to figure out what to do, the best way they could — and a lot of that ended up becoming just how to provide end of life care with dignity.

Pre-Covid, Charles normally spent a shift sitting bedside with patients, teaching medical residents how to use ultrasound equipment to detect abnormalities. When Covid struck hard and medical school was halted, his day began to look markedly different.

“Every day I’m seeing elderly patients who are alone because their family can’t come in,” he remembers. “They have tears behind their breathing apparatus. All I could do was make sure they were not alone, hold their hands, and be there for them as they passed.”

“When I’ve lost patients, I take pride in making the end of their life dignified. It’s very important to me. But at its height, I just didn’t have that luxury and it bothered me.”

When asked how things changed as the virus spread and doctors knew more about what to do, Charles speaks quietly: “It didn’t change. Not for some time.”

While the news media was beginning to tell us about standing six feet apart, social distancing, and hand-washing, Charles didn’t have patients who could receive those messages. “My patients were intubated,” he says. “They were not talking. I was calling their children and asking how they wanted to handle the end of their parents’ lives.”

While managing these extreme work pressures, Black doctors also had to have an eye on patients in communities of colors who were not getting proper treatment. “I don’t want to say my White doctor co-workers are racist or don’t want the best for all patients,” says one doctor, who LEVEL agreed not to name because he spoke without approval from his hospital. “But I did notice things sometimes, and would have to gently remind a doctor about a Black patient [left] in the hallway for far too long. Or a patient asking for pain meds and not being heard. Any Black patient in my ER becomes my patient, even if they are not assigned to me. That’s stressful as well.”

Sylvester Foote, a registered nurse and nurse manager, still winces when he thinks back to the early days of Covid. In the beginning, the virus was thought solely to be respiratory. If patients came in with other symptoms, like headache and diarrhea, Covid-19 didn’t occur to them — and neither did taking precautions. “That was an eye-opener,” Foote says. “We were all going to have to be extra vigilant no matter what.”

And, like most, Foote found himself mourning patients more often than sending them home — and doing so under circumstances that were less than ideal. “When I’ve lost patients, I take pride in making the end of their life dignified,” he says. “It’s very important to me. But at its height, I just didn’t have that luxury and it bothered me.”

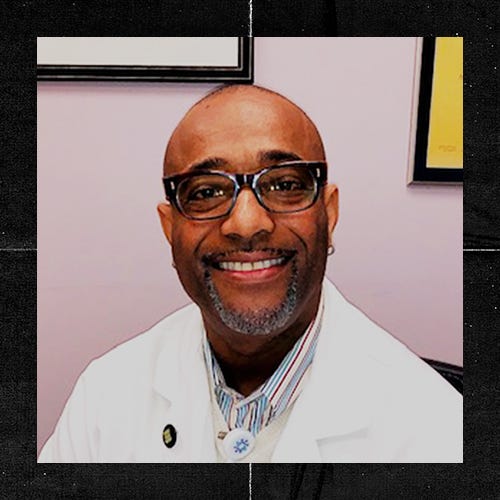

Dr. Antonio Thomas, an emergency pediatrician who also has a private practice, co-signs the common knowledge that children have been generally spared from Covid. And transmission rates even in schools have been lower than what we thought they would be. Some young children who are asymptomatic have Covid and recover with no issue, though some have inflammatory disorders later.

“The real risk with children is that they can pass it on,” says Thomas. “And in Black and Brown communities it’s more common. We are more likely to be essential workers, we are more likely to live in multigenerational households. This is something doctors need to know and think of when seeing patients. And there’s a mistrust that keeps some from the doctor overall.”

All the doctors we spoke with mentioned a single dark part of our history’s past that remains in their minds as doctors of color: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a 40-year study that shattered the first rule of medicine. Do no harm. For many years, before and since, Black folks have been leery of the medical profession.

That’s not helped by current demographics. According to most recent stats, only 2.9% of all physicians are Black men — a lower proportion than in 1978. That number means that most Black men going for medical care are not seeing a doctor that looks like them. It means they’re likely going to experience institutional bias in a doctor’s office or emergency room, even with doctors who think they’re not biased. We joke about using “tussin” for everything from skinned knees to pneumonia. If we can find a way around going to a doctor, we often do. Which is one factor in how so many of Dr. Charle’s patients came to the hospital just in time to be intubated and sent to the ICU.

And of all those patients that were intubated and sent to the ICU, how many did Dr. Charles later discharge and send home? “One,” he says. “Maybe two.”

What of the future? How do we move on through more spikes and a vaccine and more adjustments?

“Covid is here, period,” says Dr. Thomas. “Let’s get informed and continue to fight it. Our children have questions? Answer them. As a pediatrician, it’s the best thing I can do. Kids who don’t have sports and social lives will be affected by this. We’re seeing depression and other issues with teens especially. They’re not getting Covid as much — but they’re still suffering.”

As we enter the next phase of our fight against Covid-19 — one in which a vaccine reduces its incidence, but it remains a periodic concern like the flu or common cold — Dr. Bell wants to see Black men get their primary care physicians on the line and take care of those wellness exams, particularly prostate exams and colonoscopies.

“It is not comfortable,” says Dr. Bell. But if you get a clean bill of health, you’re good for five years. And if you don’t get a clean bill of health, you’ll be glad you got diagnosed!”

Bell says that he belongs to two groups of Black men who historically don’t take their health care seriously: retired athletes and physicians. After his professional football career was cut short from an injury, he went from pre-season and postseason physicals to not checking in at all.

“After Covid, I got serious,” says Bell. “When things opened back, I got all my checkups. I have to tell Black men in particular: Get to the doctor. Even as a doctor myself, I know it’s hard to do. Do it anyway.”

Dr. Charles, who calls himself a health junkie, has always kept up with his screenings. But Covid sent him to a different health professional — a therapist. “I am a God-fearing, church-going person,” he says. “I always have been. But Covid has shown me that I can also be vulnerable, not stoic and leaving the pain at work. I can talk it out with a professional. It’s been freeing.”

When it comes to the biggest change these men will take into 2021, the answers varied: going to therapy, taking time off when possible, checking in with family.

Dr. Bell had a simple answer. “I’m wearing a mask.”

“Not just outside,” he continues. “In the ER. For years, I would walk in and see a coughing, sneezing patient and I would think: My immune system can handle it. I’ve had every cold, flu, virus. I’ve done pediatric ER work. I’m fine. No more. If I walk into any ER to see any patient, I’ll have on a mask.”