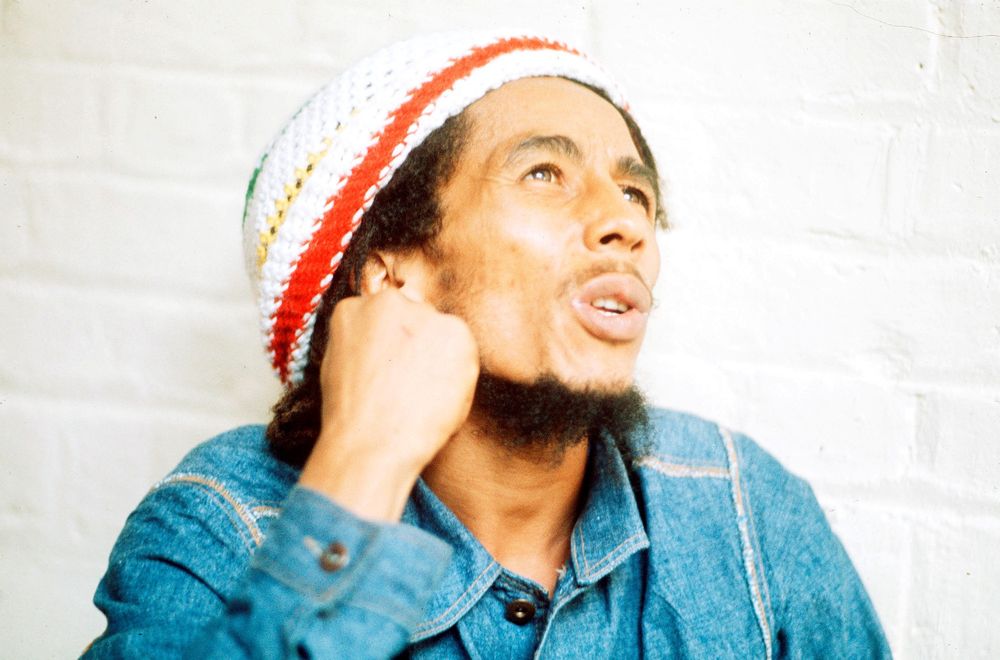

On May 31, shortly after the explosive beginnings of global unrest following the police murder of George Floyd, 24-year-old Zuri Marley uploaded a video to Instagram. In the clip, her grandfather, Bob Marley, is 28 years old. His iconic dreadlocks are only down to his shoulders as he sings the first lines of a song from the 1973 album Burnin’: “This morning I woke up in a curfew/O God, I was a prisoner, too — yeah!/Could not recognize the faces standing over me/They were all dressed in uniforms of brutality.”

As a 25-year-old, queer Jamaican American navigating my feelings about my own city facing curfew in reaction to the protests, the clip and the timeliness of the lyrics struck me. It took me back to driving home with my mother in Cleveland, Ohio, when I was 12 years old. A trembling black woman approached my mother’s car, begging for a ride to get away from her abusive partner. I turned to my mother, expecting that she would help, but instead she pulled away without a glance in the woman’s direction. My heart dropped.

“I trust her and we get robbed? It happened in Jamaica and happens here,” she muttered.

I viewed the trembling woman as a Black boy wanting to support a Black woman in America; my mother, born and raised in Jamaica, reacted with caution steeped in negrophobia. I thought of my family’s jokes about the “nigglet kids” in our neighborhood; their general admonishing of the Black Americans’ laziness: the advice they directed at me, “Don’t act like those White kids out there. Or like those hoodlums.”

In newly liberated Jamaica, it was poverty that could get you killed; in America, it is your Blackness that can get you killed. This is why the American dream for immigrants can come at the cost of understanding Black America. Our proximity to Blackness becomes our proximity to death.

In White America’s eyes, of course, distinctions like those my mother made mean little. A 2019 New York Civil Liberties Union report on stop-and-frisk encounters from 2014 to 2017 showed that the five neighborhoods where residents were most prone to experience excessive force included large African, African American, and Caribbean populations. But just because police murders of Caribbean immigrants like Amadou Diallo and Patrick Dorismond can be folded into the national dialogue around police brutality today does not mean diasporic solidarity has been achieved. Our reality together must include visions of communal survival and understanding to do so. To understand why our reality does not, we must look backwards.

Three years after Jamaica achieved independence from Great Britain, the United States passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This act allowed for more immigrants of color to flock to the United States and enabled chain migration. At the time, Bob Marley was 20 years old. His childhood in the Trenchtown ghettos had been marked by “rudeboys” establishing gangs that would later become aligned with the island’s two main political parties, the Jamaica Labour Party and the People’s National Party. In 1963, Bob Marley had become a part of ska group the Wailers, and in the coming years, he would become a devout follower of Rastafarianism, a religion with political ideas inspired by Jamaican-born political thinker, Marcus Garvey. By 1966, Jamaica descended into political tribalism between the Jamaica Labour Party and the People’s National Party, which worsened as both parties used local gangs of rudeboys for political intimidation, leading to numerous shootings, bombings, and the 1966 declaration of a state of emergency.

At the time, Bob Marley was 21 years old, newly married, living with his mother in Delaware, and likely watching news of the violence ripping through his island from afar. Nascent Rastafarianism and the newfound media-enabled proximity to Black America enabled Jamaicans to engage with Black ideology in new ways. Bob Marley returned to Jamaica from the United States to reportedly avoid the draft for the Vietnam War.

As Jamaica’s most successful musical artist, Bob Marley may have been the first Jamaican to confront W.E.B DuBois’ concept of double consciousness — the experience of seeing yourself through the eyes of the racist structure you live. He worked to articulate that through songs like “Buffalo Soldier,” a proud declaration of Jamaica’s connection to Africa. Marley’s battle with double consciousness takes on a new meaning when we consider that as one of Jamaica’s first global icons, he played in many countries where concertgoers reacted to reggae’s vibe rather than its political, liberatory lyrics. A 1981 Rolling Stone article revealed that many Black Americans thought of Marley’s music as “slave music” or “jungle music.” Marley was fed up with White critics’ and Black DJs’ prejudice toward his music, culture, and style; despite his money and acclaim, he could not fully overcome a music industry that worked to dilute the authenticity of Caribbean artists to make them more palatable to White audiences. That same year, Marley died at the age of 36. Forging deeper connections between Caribbeans and Black Americans would take much more time than he had.

But decades later, his granddaughter would pick up the mantle. Born and raised in Kingston, Zuri Marley moved to New York City in 2013 to study music at New York University. While working with producer Dev Hynes, she began to question her own sexuality — a broadening of perspective that soon spilled over into all parts of her life. “Even the way I see Jamaica and the Caribbean is completely different,” she says. “I can see it through a queer lens. I can see it and make it into my own thing and talk about it in my own way because I understand what it’s like to move through the world as a Black woman, a pansexual.”

Once in the United States, she watched films like Rent, Paris Is Burning, and Tongues Untied, which expanded her understanding of Black American culture. “When I watch Paris Is Burning, I see dancehall sessions,” she says. “I see the same movement. I see the same struggle just in different ways.” That sense of similarity was new; popular films had skewed her impression of Black Americans with stereotypical depictions of poor gangsters. “Until you see what is going on in America firsthand or experience it firsthand, you don’t really understand,” she says. “There are so many stories that aren’t heard. Having African American friends changed my perspective and helped me understand.”

In 2014, she joined in protests following the verdict against the police officer that killed Eric Garner and narrowly escaped being arrested with her friends. “It definitely changed me,” she says of her shift towards double consciousness. “No matter who you are, you’re Black. No matter where you come from, who you come from, if you’re famous or not famous, nothing matters when you are in front of a racist police officer or when you’re at the front lines.”

In her own family today, Zuri sees the cultural struggle between Jamaica and America. She explains that some of her cousins born in the U.S to Jamaican parents “speak patois, even though they were not born in Jamaica.” Conversely, she notes that Jamaican American family members who have been born and raised in the U.S. have known circumstances — like living in underserved communities — that are more associated with the Black American experience.

My own family immigrated to the United States in the late 1970s. My grandmother worked as a cleaner at a country club; when asked what she remembered of the Black Power era, she simply said, “I didn’t have time to look up from my work.” In the 1980s, during the crack epidemic, a number of men in my family went to prison for drug dealing and were deported. The 1992 Rodney King riots prompted my mother to express opinions like, “Why Black people always gotta tear up their own neighborhoods?”

In newly liberated Jamaica, it was poverty that could get you killed; in America, it is your Blackness that can get you killed. This is why the American dream for immigrants can come at the cost of understanding Black America. Our proximity to Blackness becomes our proximity to death.

When Michael Brown was murdered and I marched to the Ferguson Police Department during Ferguson October, I realized that my Blackness — which was both related to, and distinct from, my family’s Jamaican roots — deserved to be honored. My relationship to my Blackness would always be different than how my mother’s generation related to theirs. My queerness complicated my relationship to Jamaica and Black America, but gave me a deeper perspective on both.

I grew dreadlocks, which made my mother worry about my job prospects; when I started to read Joshua Bloom’s Black Against Empire, a history and analysis of the Black Panthers, she jokingly called me “Father Africa.” My political reading and organizing work brought me to this year: living in Columbus, Ohio, dodging tear gas canisters in the Short North during protests, racing home to beat curfew, reminiscing on “Burnin’ and Lootin’,” and wondering where we go from here.

Today’s political unrest only proves further that Black Americans and Caribbeans are still grasping for ways to reach each other culturally and politically. The 1960s and 1970s catapulted many Caribbean artists to the global spotlight in a way that suggested cultural exchange but didn’t often deliver it; the crack epidemic and war on drugs in the 1980s and 1990s enhanced the potential for newly freed Jamaica to fully understand White supremacy’s assault on Black America. Younger generations of Jamaicans and Jamaican Americans, like Zuri Marley and me, understand that Caribbean American Black solidarity has not fully materialized yet. All the while, we are finding new languages and ways to relate to Caribbean and Black realities.

Bob Marley may never have achieved the success that he wanted in Black American communities during his lifetime, but from 1978 to 1980, he reached another kind of dream as a Pan-Africanist by visiting Kenya, Ethiopia, Gabon, and Zimbabwe for the first time. His 1979 song “Zimbabwe” became an anthem for Zimbabwean freedom fighters; in fact, ecstatic at the opportunity, Marley funded the equipment and travel for his band to play at Zimbabwe’s Independence Day celebration. During the concert, freedom fighters rushed through barricades outside the venue, and crowds were teargassed. One by one, members of the band left the stage coughing, their faces burning, leaving only Marley standing alone on the stage, seemingly in a musical trance. “Now I know who the true revolutionaries are,” he told them when they returned.

In Bob Marley’s words, we get a sense of what Caribbean, Black American, and African solidarity can look like: a being willing to die with your people, no matter what the situation. To others, like my generation of Caribbeans, Caribbean Americans, and Black Americans that live at the intersections of so many identities and experiences, solidarity and cross-cultural understanding must go beyond surviving and dying together. It must enable us to be more to each other than what the White gaze reduces us to. True solidarity requires that we recognize all collective visions of liberation, including those of Caribbean and Black LGBTQIA+ people and critiques of how capitalism binds the Afro-diaspora.

When all the illusions are broken and solidarity is achieved, a new and better world becomes possible. “Money can’t buy life” were the last words Bob Marley spoke to his son Ziggy, Zuri’s father. In other words, Babylon can’t save you — so we have to find a way to save ourselves.