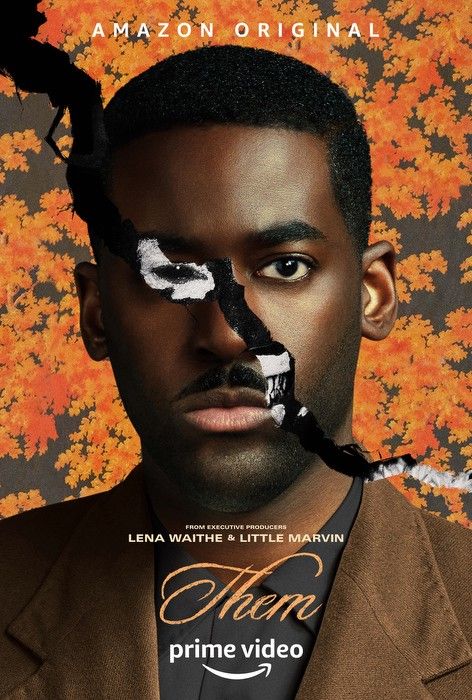

Along the course of writing this essay on Amazon’s new series Them: Covenant — in which I intended to recount my deep history with horror films and how Jaws ruined me for life — Duante Wright was killed by police in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. Shortly thereafter, body cam footage from the March 29 shooting of 13-year-old Adam Toledo in Chicago hit the internet.

As I write this, Black America is reeling, the bodies of our people shoved through a systemic machine that churns out stacks of Black victims. We hadn’t even gotten to the hashtag part of one killing before we are faced with the gruesome visage of a dying child, shot while surrendering. And it is in the midst of this collective grief and anger that I can think of no better example of why no one should engage with Them.

The horror drama series was a suspicious prospect from the start: The story of an already traumatized Black family moving into a White enclave, beset upon by every corner of society and the very ground their home rests on. It’s a rollercoaster ride of grief and gut punches with no reprieve, each episode compounding the violence of racism in escalating beats to a frustrating and exhausting anti-climax that surely would’ve ended in even more horror if allowed to run a minute more.

The racialized violence of Them is like watching the opening-bid stage of a Spades game. One player asks, “How many books you got? Because I got redlining, rape, and PTSD right here,” only to have their partner double down. “Well, I can stack that PTSD with government experimentation, then some infanticide, minstrelsy, and body horror,” they say. And then they proceed to run a Boston.

Creator/writer Little Marvin is on record suggesting all of this trauma is a win for the culture, that all of the Black people I never got to see in horror films are compensated for in Them by stress-testing a Black nuclear family into physical and psychic annihilation. As a lifelong fan of horror, I have to ask: How many Black people were actually asking to be murdered in horror films, exactly? When Jordan Peele made a similar comment during the marketing for Get Out, he made it clear that while he wondered where all the Black people in horror films were, he wasn’t suggesting he wished we’d die more, and his body of work to date reflects that. His Black characters are tragic figures, but they ascend. They behave like real people, and because they’re Black, they use all of the advice we’ve shouted at movie screens for generations and survive.

I need everyone behind the curtain of Them to understand that if I wanted to be traumatized for 10 hours, I already have America to watch.

Marvin doesn’t bother striving for such lofty goals. He’s seemingly interested only in Black representation in horror, regardless of the effect or outcome. There is no sense — common or otherwise — in the actions of the protagonists. The family moves into the last neighborhood they should, engages neighbors in ways that would’ve gotten them killed in real life, and even terrorizes one another as the formula requires. In the end, the Black characters behave like White people do in horror films, making Them the Justice Clarence Thomas of horror films.

As I scroll my media feeds right now, I am inundated by actual stories of racialized terror, and last week maddeningly so. And when I consider how so many of these stories come to me days or weeks after the killing moment, I’m reminded that some version of this is happening somewhere every day in America: Some Black family is still being run out of their home. Some Black person is driven to despair every day by the unbridled racism in their workplace. Some Black child is being purposefully undereducated by a teacher who sees and seals their fate as a foregone conclusion. Because of this reality, Them feels like the fictionalized sections of a documentary on racism. Here is how bad things used to be, the shows suggest. But who didn’t know that? And why bother making it a period piece in light of the way things are?

The effort it takes to get a Black film, television series, or book into the zeitgeist is nearly insurmountable. Because of this, there’s a contingent of Black people who believe that when you have a problem with Black art that makes it through the machine, you should keep any negative criticism to yourself. Kenya Barris confronted this belief head-on in an episode of #blackAF, this idea that to criticize such work makes it harder for all Black art to get out the starting gate, let alone succeed. These admonishments frequently come from people who already work in such industries and who want audiences to know that it’s sometimes a miracle that Black work of any kind gets through. I need people like that to understand that I understand but disagree on the cost–benefit analysis. I want our work to stand up against the best work there is because Black artists create at that level all the time but receive little of the benefit or glory. Frankly, most of what we’re competing against started with us. But I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I’d rather we spent more time considering what we’re willing to do to make it. I’d rather we consider what aspects of our existence are worth excavating for the purpose of entertainment, Black or otherwise. (I assure you that on a platform as large as Amazon, Black people are not the primary audience consideration.)

There’s a reason why the criticism about trauma in Black art keeps coming up: Because it’s real. Representation is a case you can only make for so long before we need to consider the effects of that representation. Black art does not exist in a vacuum. If representation is truly a worthy goal, I should be able to speak on the nature of the representation, as I am its subject. And I need everyone behind the curtain of Them to understand that if I wanted to be traumatized for 10 hours, I already have America to watch.

Let me be clear: I don’t want to tell artists what to create. As an artist, I can tell you that the last thing I’d want is someone telling me what to do — it’d almost assuredly have the opposite effect. But we have to be able to talk about when Black art isn’t doing what its creators believe it’s doing, or when the goal isn’t reading the room and may, in fact, be having a deleterious effect. Them is not worth the trauma it causes, and it is not worthy of the pain it mines.