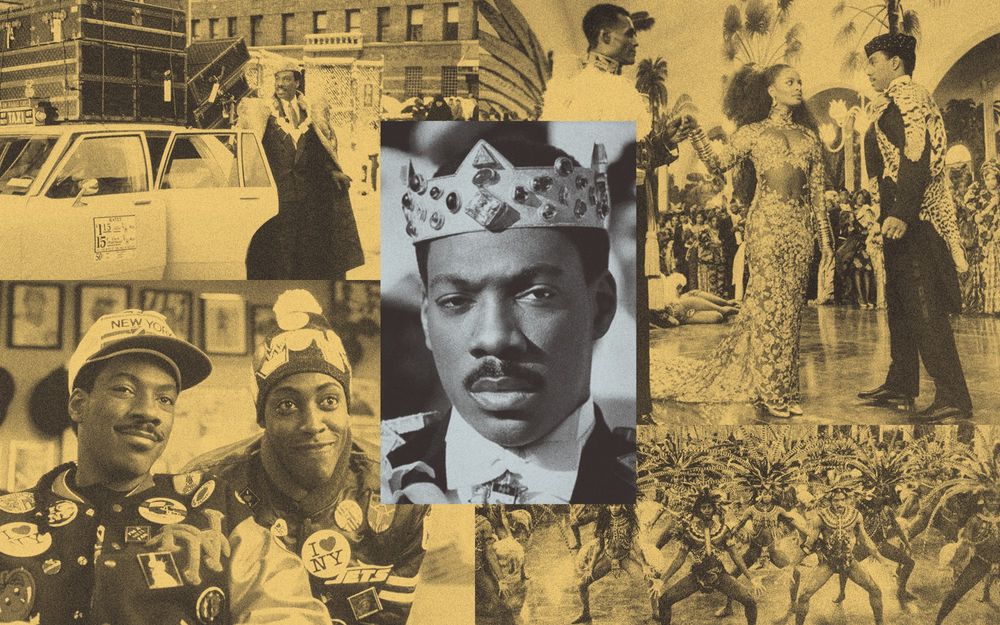

In 1987, Eddie Murphy was Hollywood’s Golden Child. He possessed a Midas touch that could pull a hundred Ms out of the box office with “a piece of shit.” (The cinematic turd Eddie referred to in a 1989 Rolling Stone interview was, in fact, The Golden Child.) He was on such a hot streak that Paramount Studios obliged his every request and whim. When the Saturday Night Live GOAT wanted his own film production company, he got it; when he requested a TV production company, he got that, too.

Eddie Murphy Television’s first project was the HBO collaboration the Uptown Comedy Express. The hour of sketch and stand-up comedy starred Marsha Warfield, Robert Townsend, a prime-approaching Arsenio Hall, and sizzling new comedian Chris Rock. But while the audience featured a constellation of ebony celebrity — from Jasmine Guy to Earvin “Magic” Johnson to Sammy Davis Jr. — the production was more Negro league than MLB. So when Murphy’s greatest cinematic triumph Coming to America became Paramount’s biggest hit of 1988, Eddie Murphy Television pitched the grand idea of bringing the Prince of Zamunda’s little brother to weekly television.

Green light.

The plot: Akeem, now the king, sends his unruly little brother Tariq to New York City to attend Queens College. Tariq was played by an uber-talented new firecracker on the L.A. stand-up scene named Tommy Davidson. Paul Bates reprised his movie character Oha (“she’s a queeeeen to beee”), now Tariq’s personal aide; John Hancock also appears (as their landlord and eventual boss), as did a pre-House Party A.J. Johnson. It was Davidson, though, who seemed destined for 1990s superstardom.

“I was the singular most sought-after Black comedian in Hollywood. I established myself as a deadpan, can’t-nobody-touch stand-up. Nobody. Jim Carrey, Eddie Murphy, Pryor. Nobody.” — Tommy Davidson

He’d have to wait a few years, though. While the script flossed some bright spots (in one scene, Tariq tells his landlord/new boss: “I can be a Beverly Hills cop. You can be a Beverly Hills cop, too! In 48 hours, we can be trading places!”) and went heavy on the hip-hop and pop-culture references (Run-DMC, Mike Tyson, Donald Trump), it didn’t take advantage of Davidson’s gifts. Most of that stems from the would-be sitcom’s showrunner, now-deceased TV writer Ken Hecht. A White man who had made a name penning Black sitcoms like Diff’rent Strokes and Webster, Hecht reportedly took a rigid, I-know-best approach to comedy. But what had worked on those family shows did not rule in 1989 — and a suspect fascination with Africans eating insects didn’t help. CBS declined to pick it up as a series.

The episode did end up airing — on CBS Summer Playhouse, an anthology series dedicated to testing the network’s pilots — but it remains a frustrating what-coulda-been for its cast and crew. We spoke to some of the folks closest to the production in an attempt to unearth what happened, what went wrong, and how Black culture missed out on Eddie Murphy Television pioneering something that In Living Color, The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, and Martin would provide just a couple of years later.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mark Corry (Vice President of Eddie Murphy Television): This was a symbiotic relationship between Eddie Murphy Television, Paramount, and CBS. We had a first-look deal with CBS. CBS came to us and said, “We’ll give you 13 episodes; just make sure you talk to us before you go anywhere else.”

Shelly Clark-White (Dialogue Coach; Executive Assistant to the President of Eddie Murphy Television): Since it was Eddie’s idea, Paramount said, “Okay, we’ll let you have the TV company, and you can have your boys, but we need someone in the industry who is able to actually make a deal.” In other words, we need somebody White over there if you’re serious. So they gave him Mark McClafferty.

Mark McClafferty (President of Eddie Murphy Television): I joined Eddie’s company in 1987. Paramount wanted to invest a lot of money into Eddie’s company and I guess they wanted someone who knew their way around the network studios. I met Eddie on the road performing. I flew out to Detroit to see if he wanted to work with me. We kind of hit it off right away. I didn’t sleep for three days. It was constant — him performing, us partying, hanging on the bus. I was like, “I’ve got to get back to work, Eddie.”

Clark-White: I knew that Tommy Davidson was a real talent. I had gone to see him live and loved his show. I was playing him up a lot. I had been actively trying to get Eddie Murphy to go see Tommy at the comedy clubs, but at first he was kind of resistant.

Corry: We had to see Tommy at a club, either The Comedy Store or The Improv. We had deals where whenever we wanted to showcase someone, we would just pick up the phone. Just like we did for Bernie Mac when Bernie was breaking into the business, coming out of Chicago.

McClafferty: I was familiar with Tommy, but I believe I saw him for the first time in person at the Hollywood Palladium, across the street from Capitol Records. He was just terrific.

Tommy Davidson: It was the hottest time in my career. I was the singular most sought-after Black comedian in Hollywood. I established myself as a deadpan, can’t-nobody-touch stand-up. Nobody. Jim Carrey, Eddie Murphy, Pryor. Nobody.

Clark-White: I thought to myself, “Oh boy, Eddie may be threatened by this kid. He’s not going to want to see him.” Eddie and Tommy both do impersonations; they both do Stevie Wonder and Bill Cosby. Tommy was breathing down Eddie’s neck. So I started telling other people that Tommy was great. Then they started putting pressure on Eddie to go see him. Eventually Eddie broke down and said, “Wow this kid’s pretty funny.”

Corry: Eddie’s the type of guy who when he’s looking at talent, he keeps his cards close to the vest. He didn’t say he didn’t like Tommy. He said, “Let’s see what he can do on his feet.” Of course, when he finally did see Tommy he was like, “Oh, that’s my man.”

McClafferty: From what I remember, everyone was on board right away. They were impressed with his talent, and Tommy had a bit of a name at the time so it was a good person.

Clint Smith (Vice President of Eddie Murphy Television): Tommy Davidson was pretty good, but we wanted Marlon Wayans. Marlon did a really great audition. He was a kid, but he killed it. He was a natural. But he already had commitments.

“I thought he was an asshole. His script was horrible. We were like, ‘That shit ain’t funny!’” — Clint Smith

Corry: Marlon was good. He did a great job. But if you put him and Tommy side by side… at that time, Marlon hadn’t done a lot of things. He was raw. This is before In Living Color.

McClafferty: When I was working with Eddie I was getting a call almost daily from a young rapper — Will Smith was like, “Please, Mark, get me in; I want to meet Eddie.” So I kept trying to convince Eddie. Eddie would say, “But he’s a rapper.”

Corry: The two actors that stood out to me were Marlon Wayans and Wesley Snipes. Wesley came in to read dressed in the full kente cloth with the hat, accent and all. He went full out to get the role. This was before Nino Brown, so Wesley was hustling. But Tommy Davidson nailed it for us. Paramount loved him as well as CBS.

Clark-White: Over time, Mark McClafferty asked, “Would you like to work on the pilot?” Production told him they needed a dialogue coach to feed lines to the actors on set. Tommy and the heavyset kid Paul Bates would come over my house every evening and we would order pizza and go over lines.

Davidson: I had choices. I had a pilot offer from CBS for Murphy Brown. I was supposed to be cast as the top guy with Candice Bergman. I also had a three-year holding deal with Disney to do anything I wanted. They were gonna pay me X amount of dollars to take me off the market to develop TV and movies for me.

Clark-White: Tommy was great but he was just starting out. So he needed a lot. I kind of graduated into becoming his personal assistant. Whatever he needed on set — whether to grab him something or be a spokesperson.

Davidson: So I picked the Eddie pilot. I’m working with Eddie Murphy. I’m gonna be collaborating with him and making this thing funny. How can I lose? You know it’s gonna be the bomb.

McClafferty: We got Ken Hecht to write the script. Paramount suggested him. We initially wanted Barry Blaustein and David Sheffield, the guys who wrote the Coming to America movie, but they weren’t available. I don’t think their agents wanted them to do it. They would’ve been the best choice.

Davidson: The executive producer, Ken Hecht, had carte blanche. The material was wack. I had a great cast, but it was more of a dictatorship style of TV : “Just do what I say.”

McClafferty: Ken’s a White guy who’s been around shows like Diff’rent Strokes, but it’s different when you’re working with children as opposed to a comic who knows how to deliver. I don’t remember Tommy being tremendously upset, but I know there was some discussion whether Ken was the right person for the job.

Davidson: I was getting resistance from day one in rehearsal.

Smith: Oh, me and Ken bumped heads all the fucking time. I thought he was an asshole. His script was horrible. We were like, “That shit ain’t funny!” But he had some credits. The studio wanted him and me and my partner were rookies. Tommy almost saved it.

Davidson: The funny stuff, I wrote.

Corry: Ninety percent of what was written was written by Ken, and I don’t remember the last time he was a Black man. There were times when it was like fingernails on a chalkboard; lines were groan-worthy. Using “eating bugs” as an example. It’s like, really? Come on, man. If that material came out now, folks would’ve been marching and protesting in the streets.

Clark-White: I remember Tommy going head to head with the writers. Tommy would question some of the lines and change them slightly like, “I would say them this way.” But of course they didn’t want to be questioned.

“Eddie wouldn’t even return my calls. His office was a 10-minute walk from the stage and he never came by.” — Tommy Davidson

Davidson: I’m improving all over the place. Killing it. Ken kept saying, “Nah nah nah, that’ll never work.” But the interesting thing was, society was changing. The perception of Blacks was not the same as the television perception of White writers that wrote Black shows. We didn’t have a whole lot of Black writers then. So I’m left with the old regime style of doing things, which is, “Shut up, Black person. I’m writing this.”

McClafferty: With movies, your director is your king on set. With TV, the producer is the king — and in particular, the writer-producer of his own show. I don’t remember any animosity, but I do remember thinking I don’t know if I’d work with Ken again.

Davidson: I didn’t get any help at all. Eddie wouldn’t even return my calls. His office was a 10-minute walk from the stage and he never came by.

Smith: Eddie never came to set unless he was working.

Clark-White: I don’t remember Eddie going over to the sound stage a lot. Maybe once or twice but he came in covert, just stayed in the back, and left.

Smith: I really didn’t want Ed hanging around because he’s my best friend. He threw us in the water and said, “Swim.”

Corry: Once Eddie charged Clint, McClafferty, and myself to do the project, he’s not going to be hands-on. One, that would be a distraction to the set. He’s got other things to concentrate on, from tours to movies. He was not there hovering. He’s like, “Just call me when dinner is ready. Don’t call me to watch water boil.”

Davidson: Had he come down there and said, “This is my show and this is my star and this is what I want him doing,” it could’ve been a situation like Roseanne or Seinfeld. Roseanne represented the poor White people in America. The comedy was coming out of her stand-up. Seinfeld was a hip Jew with his friends. The urban framework of Coming to America was based on what existed at the time. The potential of that collaboration never got fulfilled.

Clark-White: I thought the people who were in charge didn’t make it clear enough that the lead would be Tommy Davidson. Networks were thinking it was going to be an Eddie Murphy television show and they were disappointed when they found out it was not Eddie Murphy. I believe they asked Eddie to be a guest and he declined.

McClafferty: This is no disrespect to Tommy or anybody, but Eddie was the biggest movie star to come along in years. How do you watch someone play the same role and match up?

Clark-White: Looking back, Paramount probably saw the television company as a joke. They looked at it mostly as an appeasement for Eddie. They just wanted movies. Don’t forget it’s a Black man trying to be a TV producer. So they sabotaged it and put it on a day when no one was watching.

Davidson: They aired it just to air it at 8 p.m. on the Fourth of July. I was so excited about it, but nobody watched it, and that shit hurt. I’m in the house at a barbecue watching my own TV show while everyone else is outside. On top of that, CBS told us they weren’t going to pick up the show.

Corry: You would think they would maximize their dollars by putting this on when more eyeballs are on it. There are no pilots — not even mid-season replacements — that are put on in the summer. If you’re putting something on in the summer, you’re basically just trying to burn the show by fulfilling your obligation.

McClafferty: I don’t remember getting a lot of criticism from anybody on the show. I just remember it wasn’t the same as when you looked at Eddie playing the part in the movie. As brilliant as Tommy Davidson was, he was clearly in a tough position.

Smith: I didn’t totally hate it. Tommy killed it. If we had a good time slot and the studio gave us a chance, that show would’ve been a hit.

Davidson: With the loss of Coming to America was the loss of everything else. I couldn’t go back to Murphy Brown — it was already a hit show. I couldn’t go back to Disney — I already turned them down. I was at ground zero. It was so deflating that when Keenen Ivory Wayans offered me an audition for In Living Color a year later, I turned it down. I was like, “I’m not going through that again.”

Clark-White: There were always a million projects, but the closest Eddie Murphy Television came to doing something great was with Tommy.

Davidson: It was one of those things that could’ve changed my whole career. It’s a TV pilot. You go into TV for five years and then into syndication, you’re now Will Smith. I have a chance to do a major Paramount television show with Eddie Murphy producing it. That’s supposed to go into syndication for the rest of my life.

McClafferty: As much as people might have thought it was a slam dunk, you’re taking one of the most successful movies ever and trying to translate it as a television show. It’s not an easy thing to do.

Davidson: You got to be able to take some defeats and still have faith. Eddie Murphy and Keenen ain’t gonna tell you a fucking thing, ’cause they don’t give a fuck about you. I had to learn that and take that like a man and not be like them.