I was nervous about watching Bamboozled in 2020.

Spike Lee’s 15th film, originally released in 2000, is a satire about the entertainment industry, race, and America’s love affair with minstrelsy and blackface. At the time, it was an obvious and necessary reaction to shows like The Secret Diary of Desmond Pfeiffer, the embarrassingly stereotypical (and thankfully short-lived) UPN sitcom about a slave and his owners.

I saw Bamboozled when I was 16. At the time, the problem wasn’t just Desmond Pfeiffer; shows like Homeboys in Outer Space prompted Lee to say that he’d rather watch Amos ’n’ Andy than anything on UPN or WB. Like many Black kids my age, I knew that the versions of Blackness that studios and networks were putting into the world weren’t right but in ways I didn’t quite understand or have language for. Bamboozled gave me that language and earned my loyalty in return; I spent most of my adult life calling the movie my favorite of all time. So when the news came that Bamboozled would be entering the Criterion Collection, a library of lovingly restored movies revered by film nerds, I knew I wanted to write about it. However, writing about it would mean that I’d have to revisit a movie I’d championed but hadn’t seen in years. Let’s just say it: I was worried that the movie would age like a racist White lady.

After all, Lee in the post-Bamboozled years has been at his worst when he’s using movies as a soapbox: think 2012’s Red Hook Summer and especially 2015’s farcical Chi-Raq. I was afraid that Bamboozled — which at the time also received polarized reactions from critics — would feel didactic and convoluted today, especially to a now-33-year-old me who better grasps the concepts the movie covered. I was afraid that the movie would play into the respectability politics that defined the late ’90s, when gangster rap was seen as the bane of Black existence and Bill Cosby was telling us to pull our pants up.

“Spike is at his best when he is either talking about a life he knows intimately or a topic he holds dear. Bamboozled represents both of those worlds: the pitfalls of being a Black entertainer in a White machine, and a meticulously researched history of minstrelsy.”

I shouldn’t have worried: Twenty years later, Bamboozled stands as one of Spike Lee’s most brilliant, gripping productions and one of the most prescient works of cinema we may ever see. It’s a classic full stop — though not as infallible a film as I once thought it was.

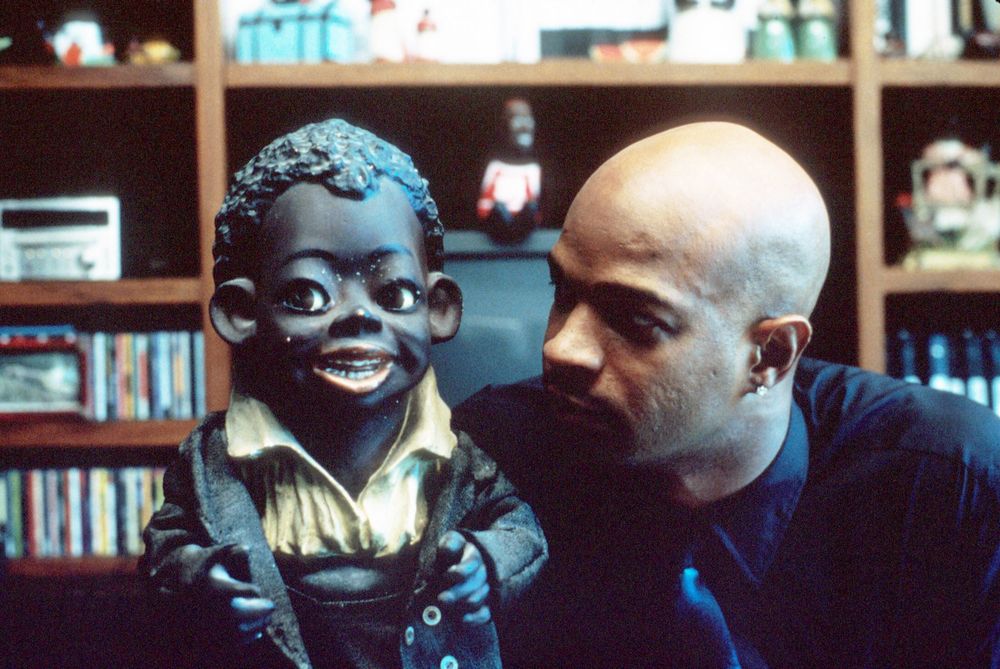

Bamboozled focuses on Peerless Dotham (expertly played by Damon Wayans, faux-European accent in tow), a TV writer frustrated with his job at a cable network. Devising a scheme to get fired, he pitches the most racist series imaginable: The New Millennium Minstrel Show. It’s full of Black actors in blackface and set in an Alabama watermelon patch — and to Dotham’s chagrin, it becomes a massive hit, turning blackface into America’s favorite new trend.

Savion Glover and Tommy Davidson play Manray and Womack, homeless entertainers who are plucked off of the streets to star in the show under the names Mantan (a reference to Mantan Moreland) and Sleep ’n’ Eat. Jada Pinkett plays Wayans’ assistant and the voice of reason as things careen off the deep end. And Michael Rapaport plays a racist TV exec who thinks he’s too in tune with Black culture to be racist; in other words, Michael Rapaport plays Michael Rapaport’s tweets. All of them turn in peak career performances — especially Davidson, who shows emotional range and otherworldly charisma, and Pinkett, who was the absolute heart and soul of the film.

Spike is at his best when he is either talking about a life he knows intimately, i.e. growing up in New York (Crooklyn, Do The Right Thing, or even his HBCU experience for School Daze), or a topic he holds dear (Malcolm X and documentaries like When The Levees Broke). Bamboozled represents both of those worlds: the pitfalls of being a Black entertainer in a White machine and a meticulously researched history of minstrelsy. That’s why the execution, like an early discussion about why shows portraying Black characters in a positive light don’t get greenlit, is so precise.

It’s astonishing and alarming how well Bamboozled anticipated 2020. Twenty years ago, the idea of a blackface resurgence felt dystopian; today, “blackfishing” and the Kardashians’ history of plastic surgery, fake tans, and hair crimes proves that while the shoe polish might be gone, White people will always flock to the Blackness of their own imaginations. As Paul Mooney’s Junebug says in one scene: “Everyone wanna be Black, but nobody wanna be Black.”

But it was a moment 20 minutes or so into the film that made me sit back with my mouth agape. Rapaport’s executive character is listening to Peerless’ pitch for the new show and wants to see Manray tap dance for a sample of what to expect. The exec clears his desk; Manray gets on the table and starts tap dancing for him. The scene is demoralizing and a perfectly (for Spike) unsubtle way of showing how Black people are asked to perform for White men in power. While Pinkett mutters her disapproval under her breath, Rapaport has his hands in the air as if he’s getting a lap dance. It’s an inflection point in the movie — but watching it today, it hit me like a boot to the chest. I’ve seen this before.

In 2014, unsigned rap phenomenon Bobby Shmurda performed for Epic records. In front of — and on top of — a table. In a room full of White executives. He danced. He rapped about guns and murder. And he got a record deal. A few months later, he was arrested and is still serving time in jail for conspiracy and weapons charges. Those White execs have moved on with their lives; Shmurda can’t. You can’t watch that Shmurda video and see anything but Manray tap dancing on the table. It’s just one of the ways that Bamboozled was soothsaying in ways I’m not even sure Spike knew would be possible.

Bamboozled also tapped into the future world of social media and the evolution of crash TV and how that affects Black people who are subjected to it, especially when it’s the Black body that we see in pain on our screens. The climax of the movie showed a world in which executions are played out over what was then still just the “world wide web,” traumatizing viewers. A few years later, we saw the ways that video footage of police brutality against Black folks affected the collective Black psyche. The movie even nails the self-destructive futility of the misguided hotep cults — like the Mau Maus, who only harm Black people in a convoluted quest for a twisted vision of revolution.

But maybe most importantly, Bamboozled features a trait rarely seen in Spike Lee movies: nuance. If there’s one criticism of Spike, it’s his penchant for hitting us over the head with his point. Traces of that persist — the movie opens with a Webster’s definition of “satire” like it’s a ninth-grade essay — but the movie’s argument about modern-day minstrelsy is layered and resists giving a clear answer.

Lee is careful not to condemn Black comedians like Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence, whose Nutty Professor II: The Klumps and Big Mama’s House had achieved massive success, and massive criticism, the year before. Even castmembers Wayans and Davidson had been criticized for “coonery” for their work on ’90s sketch show In Living Color, but their inclusion in the movie signals a pushback to that notion. Lee leaves the true definition of modern-day cooning up for audience interpretation, and we’re left to ponder if the bigger “coon” is the people who don the blackface or the writer who sells out his own behind the scenes.

To further complicate the debate, Lee makes the blackface scenes legitimately hilarious. It’s a brilliant move; we judge the minstrel show’s studio audience in the movie for laughing — then question why we’re laughing as well, all while being reminded that the Black men and women who engaged in minstrelsy were all profoundly talented in their own rights. It’s one of the most ingenious tricks Spike has ever played.

The movie isn’t perfect: It undercuts its own foray into addressing sexism, but short-changing Pinkett’s character and her masterful turn as the movie’s conscience. (A Black woman repeating “you should have listened to me, you never listen” is also one hell of a prescient refrain). But the payoff, in the end, is the documentary-style montage of early 20th century clips of blackface and minstrel shows that were so emotionally draining that I couldn’t even bring myself to watch it until the next day, once I’d mentally prepared myself.

Bamboozled isn’t perfect the way I once thought. But it still represents Spike at his most focused, most critical, and most incisive about the American culture-industrial complex — and the oppression and racism embedded within it. And while we didn’t know it then, it was both a reflection and a warning, crying for the past and raging against a future that was racing toward us all.