When I was young, I was a big fan of the original Killer Instinct games.

My favorite character was Glacius, a powerful being made of ice. You could turn his hands into weapons or melt down to a puddle, reemerging with an uppercut to opponents. Other characters in the game were the sword-wielding warrior monk Jago; Sabrewulf and Riptor, a werewolf and fighting raptor; Spinal, a skeletal soldier; and a brutal cybernetic soldier named Fulgore.

There was also TJ Combo. Though this boxing champion has one of the illest Ultra combos in fighting game history, he seemed a bit mundane compared to the other characters.

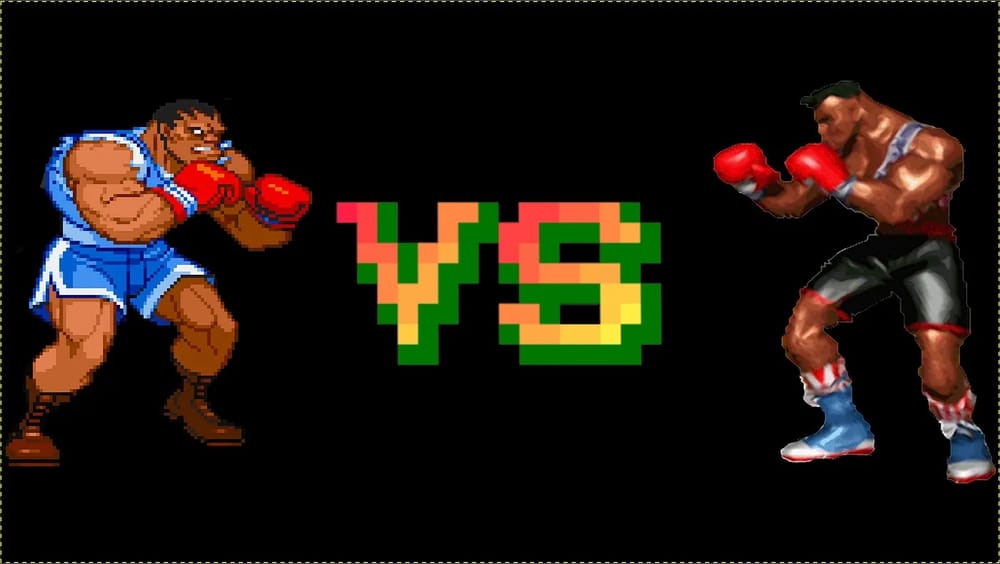

From Balrog in Street Fighter to Jax in Mortal Kombat, Black characters in the most popular fighting games are often boxers, or at least, their primary form of combat is punching. They also tend to be weaponless fighters battling against other characters who range from super-beasts to energy-wielders to deadly weaponry experts.

The Black boxer trope carries subtle conceptions about Black men as paradoxically both superhuman and inhuman. How else can Black men defeat fantastic foes — deities, demons, mythical beasts, martial arts experts, wizards, cyborgs, people who can shoot balls of fire or lightning from their palms — with nothing but ‘these hands?’

The Black boxer trope’s origin is most likely not nefarious, rooted instead in the ’80s when the popularity of boxing and video games converged. World heavyweight champion Mike Tyson was the primary inspiration for Balrog. (Though unconfirmed by Capcom, the character’s name was initially M. Bison.) Many of the first games to feature Black characters were sports games — Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!! and Frank Bruno’s Boxing were both released in the late ’80s. Over time, Black characters have become much more commonplace in today’s video games.

Game developers often created character archetypes through stereotypes, especially in fighting games. They used stereotypes to connect to players’ heuristic understanding of racial groups. For example, the average American gamer may not be abreast of much Japanese culture or history, but “ninja” or “samurai” is likely a part of their pop cultural imagination. Capcom framed Street Fighter II as a world tournament, so they used archetypes and stereotypes from different parts of the globe.

Virtually no large national or ethnic group is immune from this treatment — tomahawk-carrying Native fighters, Irish boxers, Japanese sumo wrestlers, Indian gurus, Amazonian women warriors, English knights, kung fu masters. It’s just as salient in other forms of pop culture, like professional wrestling (which offers probably the most unfiltered racial theater and stereotypical depictions outside of pornography).

Stereotyping is also quicker; it allows game devs to move into the technical side of development without needing to do a ton of research to craft characters’ backstories. Though problematic, stereotypes are also seen as efficient, as they allow players to fill in the gaps of a character’s backstory. If a character is a ninja, you bring preconceived ideas of their training and skills.

While the player’s enjoyment of a game is partly based on the suspension of disbelief, it also comes from realistic elements like a character’s fighting techniques or the game’s world-building. Though fictional worlds are not real in the material sense, they still have to be believable.

It’s interesting to consider how these characters fit within the world of their games and how race makes characters legible to players. We shouldn’t dismiss more banal reasons like lack of research or more problematic ones like reliance on stereotypes. Still, I wonder how much of the Black boxer trope reveals our cultural imagination about Black masculinity (since most mainstream fighting game characters, and almost all Black fighting characters, are male).

Many of the other playable characters in fighting games have powers or use powerful weapons. The only weapons Black boxers have are their fists. The trope carries subtle conceptions about Black men as paradoxically both superhuman and inhuman. How else can Black men defeat fantastic foes — deities, demons, mythical beasts, martial arts experts, wizards, cyborgs, people who can shoot balls of fire or lightning from their palms — with nothing but “these hands?” Mastery of complex fighting skills, ancient weapons, or magical powers is unnecessary when you already have a big Black guy’s brute strength. Who needs a weapon when you are a weapon?

When Black fighters do get external weapons, they tend to be enhancements, like the metal arms of Jax or Doomfist in the multiplayer first-person shooter game Overwatch. It may be aesthetically cool, but it also reaffirms the idea of Black brutes’ inherent strength and decreased susceptibility to pain. Studies show that people see Black men as larger and more threatening than similarly sized White men. With these characters, the assumption is that to defeat fighters with supernatural abilities, Black men just need to enhance their “natural” abilities.

But even stripping these characters of race, as an average player, who am I more likely to pick as a young gamer: a boxer, or someone who can shoot fireballs from their hands? A mean jabber, or a magical sword wielder? Not only is the Black boxer trope problematic in its racial implications, but it is also often the least appealing character backstory or attribute in popular fighting games.

I don’t contend that the creators of these games are intentionally evoking anti-Blackness, but at least incidentally, the Black boxer trope conforms to specific historical ideas about Black men that are often basely assumed and go unexamined. The “Black brute” stereotype traces back to slavery. It was then augmented during Reconstruction when white Americans justified segregation and anti-Black violence like lynching through the specter of miscegenation and the myth that newly freed Black men would rape white women (Ida B. Wells, one of the first black investigative journalists in US history, did foundational work uncovering this). I would argue that the Black boxer trope is a shadow cast by the Black brute stereotype.

The ease that comes with tropes and stereotypes also carries downsides. But game-makers can avoid these problematic tropes by putting in the same level of research in crafting their Black characters’ backstories as they do other characters. A great example here would be Eddy Gordo from the Tekken series.

First arriving in Tekken 3 — considered one the greatest fighting games of all time — Eddy Gordo is a Brazilian capoeira fighter who enters the King of Iron Fist Tournament to avenge his father. Capoeira is a martial arts form created by African slaves in Brazil (though scholars trace its earlier roots in Angola). They blended fighting techniques with acrobatic dance to teach each other how to defend themselves without the White slavers knowing what they were up to; at first glance, it would look like the slaves were merely dancing. Making Eddy a capoeira master was a great way to avoid stereotypes and showcase a richer character backstory.

We should also consider how gamers worldwide became prone to and maybe even interested in practicing martial art from the African diaspora after playing the game. It would be great to see future fighting games make Black characters a female practitioner of tae kwon do, a Senegalese wrestler, or even in the realm of boxing, a dambe boxer from Nigeria. However, Black characters don’t need to always be tied to cultural references. We can create Black fighters who are scientists who attack with potions and machines, girls who fight with telekinetic powers, or men with swords made of ice.

Examining the Black boxer trope in fighting games is not meant to suggest that all Black characters in fighting games are boxers. That is certainly not true, even for the games mentioned in this article. However, understandings of racial groups are forged mainly through representation. It is not everything, but it would be untrue to suggest that it doesn’t have an impact. Identifying and dissecting historical tropes can give us a more critical view of how representation in the media we love can reflect ideas about race in real life.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Joshua Adams' work on Medium.