Back in 1998, André 3000 put his own spin on that old adage about judging a book by its cover. “Is every nigga with dreads for the cause?” he mused rhetorically on the title track of OutKast’s third album, Aquemini. “Is every nigga with golds for the fall?” The point was clear: Seeing ain’t always believing, especially for his materialistic and conscious rap peers. And more than two decades later, the answers to his questions feel clearer than ever.

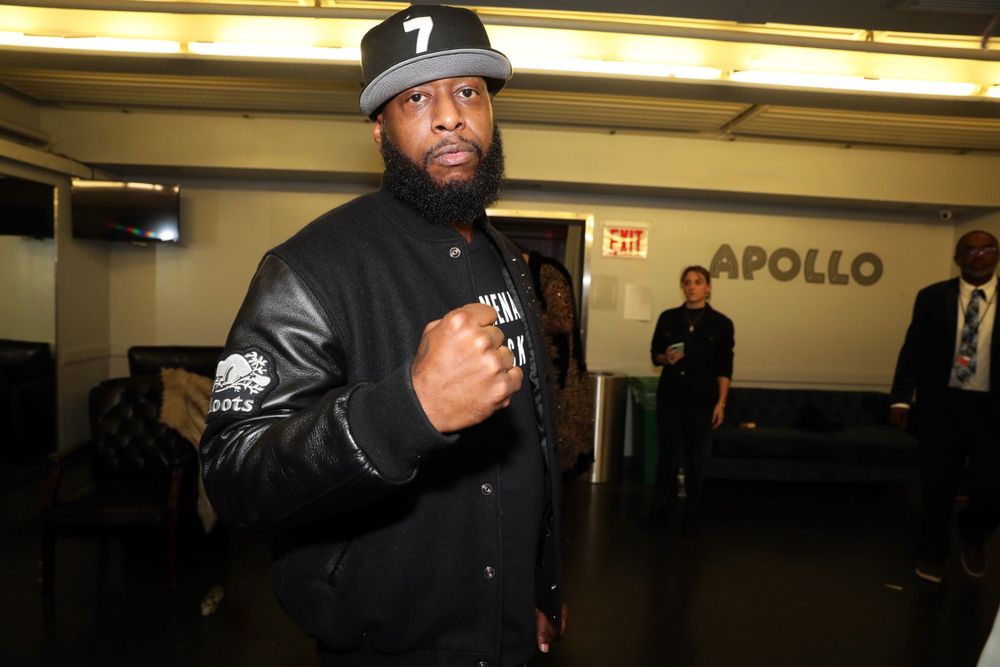

Earlier this month, in the wake of the death of The Roots’ Malik B., singer Jaguar Wright hopped on Instagram to reminisce. And with that trip down memory lane, she made some alarming allegations against artists many considered to be righteous. Among the charges, she accused Common of sexually assaulting her, Talib Kweli of hiding in a green room and watching while women changed clothes, and The Roots — with whom she worked early in her career — of fostering an environment that was generally unsafe for women. Of course fans were shocked by the as-yet-unproven claims, due to the pedestal on which these conscious acts have long been perched. Yet Wright’s assertions, which were only the latest in a recent string of incidents highlighting the abuse of Black women within hip-hop culture, underscore an important point: Never assume any individual is more virtuous than the next based solely on their art or their aesthetic.

It may feel natural to assign a degree of merit and respectability to artists who create music meant to uplift. But even among the most principled MCs, there can be a dissonance between music and reality. Before Common became an actor, author, or ambassador, he was recalling his relationship with hip-hop (as personified by a woman) on record. First there was 1994’s “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” where he lamented its commercialization; five years later, on The Roots’ “Act Too (The Love of My Life),” he ultimately accepted the culture’s expansion into something over which he couldn’t be possessive. However, Common himself will admit that he was substantially less enlightened in his younger days, before he became the de facto positive hip-hop figure. “It was ‘bros before hoes’ — stuff you’re repeating from your homies when you’re not really thinking for yourself yet,” he told The Guardian in 2019 of his mindset around the time of his 1992 debut album, Can I Borrow a Dollar?

We’re too willing to convince ourselves, and others, of what someone isn’t capable of doing. They’re “good guys.” They’re our friends. They’re our favorite rappers. And we’re complicit in our defense, our incredulousness, and our silence.

Although Common matured in many areas through the years, he didn’t stop saying the other f-word until 2007. “I was only using the word because it was part of a culture that I grew up in,” he told radio host Clay Cane in 2019, explaining his prior use of the homophobic slur. “I didn’t even think about what the word meant and how it was affecting other people.” Homophobia had been so deeply embedded in society that even after refining his perspective, Common compartmentalized his own evolution.

Being viewed as a progressive figure doesn’t mean your words or actions can’t harm someone more marginalized. On Black Star’s “Brown Skin Lady” in 1998, Talib Kweli and Mos Def declared their love and appreciation for Black and Brown women; 22 years later, though, Kweli did exactly the opposite by using his Twitter account to relentlessly harass Maya Moody — a Black woman with less power than him by way of gender and status — amidst a discussion about colorism in hip-hop. He was permanently suspended from Twitter for what the social media platform describes as repeated violations of its rules and policies. Make no mistake: this weeks-long online attack may not have been physical, but it was an act of violence.

Likewise, just because you’re not known for explicitly misogynistic lyrics doesn’t mean you lack the capacity for misogyny, or that you can’t be held accountable for it. J. Cole, one of contemporary hip-hop’s most popular everymen, learned this after releasing “Snow On Tha Bluff” in June. The song — which was released against the backdrop of global demonstrations protesting the police killings of more Black men and women, as well as the murder of Black trans women — condescends to an anonymous woman criticizing celebrities who don’t use their social capital to improve society. “Lowkey, I be thinkin’ she talkin’ ‘bout me,” he admitted. Following the song’s release (and subsequent blowback), J. Cole indirectly confirmed that “Snow On Tha Bluff” was about Noname.

Men can’t praise women for being the leaders they don’t feel qualified to be, then patronize them over their tone. Men can’t ask women to guide them in ways that still allow them to feel superior. While Cole’s actions aren’t as egregious as Kweli’s online behavior or the alleged actions of those who prompted Wright’s accusations, they’re a prime example of good-guy misogyny — a uniquely dangerous phenomenon that’s so pervasive that it’s rarely addressed (and often unnoticed). It thrives on misogyny’s firm entrenchment in a society that conditions everyone to internalize it. That’s why people can look at J. Cole, who was raised by his mother, letting single mothers live in his childhood home free of rent, and think it means he’s incapable of misogyny.

One of the main reasons misogyny is so prevalent, in both hip-hop and society, is because men enable it. Counteracting it requires a level of self-interrogation many of us fail to perform. It demands that we examine some of the people closest to us, and some who we admire, under a microscope. And it demands that we observe the person in the mirror, because we’ve likely condoned it at some point. Maybe you didn’t check a friend who crossed a line. Maybe you were condescending to a woman who said something you didn’t want to hear. Maybe you tacitly forgave someone who did something unforgivable. We’re too willing to convince ourselves, and others, of what someone isn’t capable of doing. They’re “good guys.” They’re our friends. They’re our favorite rappers. And we’re complicit in our defense, our incredulousness, and our silence. Calling this out isn’t cavalier or revelatory, because it’s nothing women aren’t saying — and haven’t been saying for years.

Perhaps much of the righteousness we confer on certain artists is just self-righteousness. Perhaps it’s time we accept that no man has earned the benefit of the doubt when it comes to the mistreatment of women. And perhaps it’s time we, as men, finally start listening to women when they explain this.