From its opening moments, watching Crash is like reading your first Tumblr think piece. “It’s the sense of touch,” says Detective Graham Waters (Don Cheadle). “Any real city, you walk, you’re bumped, brush past people. In L.A., no one touches you. We’re always behind metal glass. Think we miss that touch so much, we crash into each other just to feel something.” It’s like a rapper saying “get it?” after a middling punchline, a flailing swing at cleverness that should have told us everything we needed to know about what was about to unfold.

Sure, densely populated cities like Los Angeles break along racial and cultural lines; that part of Detective Waters fake-deep take on “touch” is true. But director Paul Haggis’ meditation on race and bigotry, which hit U.S. theaters 15 years ago this week, seems to mistake contact for intimacy.

If anything, Crash is too touchy — so heavy-handed that, over the course of its near two-hour run, the story it attempts to tell hardly even matters. The ease with which Haggis stereotypes and demeans his characters speaks to Americans’ most paranoid sensibilities. Its diverse cast and glossy ambition to tell multiple interlocking stories about race relations and volatile cultural misunderstandings helped the film feel like a progressive dream for some, and an assuager of White guilt for others.

In 2005, there were many reasons to be excited about Crash. Cheadle is just one part of a remarkably talented cast including Thandie Newton, Ludacris, Matt Dillon, Terrence Howard, Sandra Bullock, and Brendan Fraser. Haggis had just come off the award juggernaut that was Million Dollar Baby. And with Americans still lingering in some semblance of post-9/11 national solidarity, it seemed like we might actually be ready to have a serious conversation about cultural harmony.

The grace Haggis bestows White people who have otherwise shown zero potential for growth isn’t just troubling, it’s… well, it’s almost as if this film is a wee bit racist.

Many major film critics took the bait: Roger Ebert named Crash the best film of the year, calling it a film “about progress” and suggesting that it might make viewers more sympathetic people. Publications like the Los Angeles Times and Rolling Stone included it in their year-end top 10 lists. But it wasn’t all love for the slow-motion collision. Cultural critic Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose profile was still rising, called it the worst movie of the entire decade. And by the time it won three Oscars, a growing chorus had realized that its best picture win was an embarrassment.

Crash resonated with the White film intelligentsia for the same reasons that Green Book and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri did: It’s utterly basic. Haggis’ characters are walking embodiments of his worst ideas about marginalized groups — it seems, for some reason, that he hates them. Every character is assembled so familiarly, yet haphazardly, that it feels like a teenager’s sociology project on the Rodney King riots.

Take, for just one example, Ludacris’ carjacking ideologue Anthony, a bizarre blend of Uncle Ruckus and Stephen A. Smith. Anthony’s shtick — performed in tandem with his literal partner in crime, Peter (Larenz Tate) — is the angry Negro who hates stereotypes but just can’t help but fall into them. We meet them leaving a restaurant where, according to Anthony, they were treated unfairly: an hour-plus wait for food, no coffee offered.

“You don’t drink coffee and I didn’t want any,” Peter reasons. “Did you happen to notice our waitress was Black?”

“And Black women don’t think in stereotypes?” Anthony counters. “When’s the last time you met one who didn’t think she knew everything about your lazy ass before you even opened your mouth?” The substandard service, he says, was because she believes Black people don’t tip well.

How much did he leave, Peter wonders with a smirk. Anthony’s indignant response? “You expect me to pay for that kinda service?”

This racial call-and-response minigame carries through many of their interactions onscreen, with Anthony groaning about the plight of the Black man while doing everything to ensure he’s the paragon of said plight. Crash plays it for jokes, but despite a racially diverse cast, the butt of those jokes is almost always those with the least power.

To pull off a movie like this, you need more than Black faces; you need to convey what happens behind those faces. You need Black cognition, Black wit, the Black experience — and Haggis just didn’t have the range. What he did have was ambition and an understanding of L.A.’s hyperspecific cultural enclaves. What he created with that was a White redemption story written on the backs of Black people, one that received an outpouring of critical celebration for one character in particular.

Matt Dillon’s Officer Ryan was a white knight’s dream, a hurricane of racism and sexual abuse.

Viewers first meet him in the midst of a phone call in which he tells an essential worker, straight up, “I know a dozen White men who could do your job.” His toxic rampage continues as he pulls over Black couple Cameron (Terrence Howard) and Christine (Thandie Newton) for no reason other than getting a little freaky in the front seat — and then molests Christine right in front of Cameron and his own partner. It’s an infuriating scene clearly intended for shock value, but you could imagine Haggis imploring you to look a little deeper: At his core, Officer Ryan is just a man who feels powerless due to a health care system that’s failing his sick father. He’s so traumatized by his dad’s urinary tract infection, you see, that he has no choice but to be an absolute prick to every Black woman he encounters.

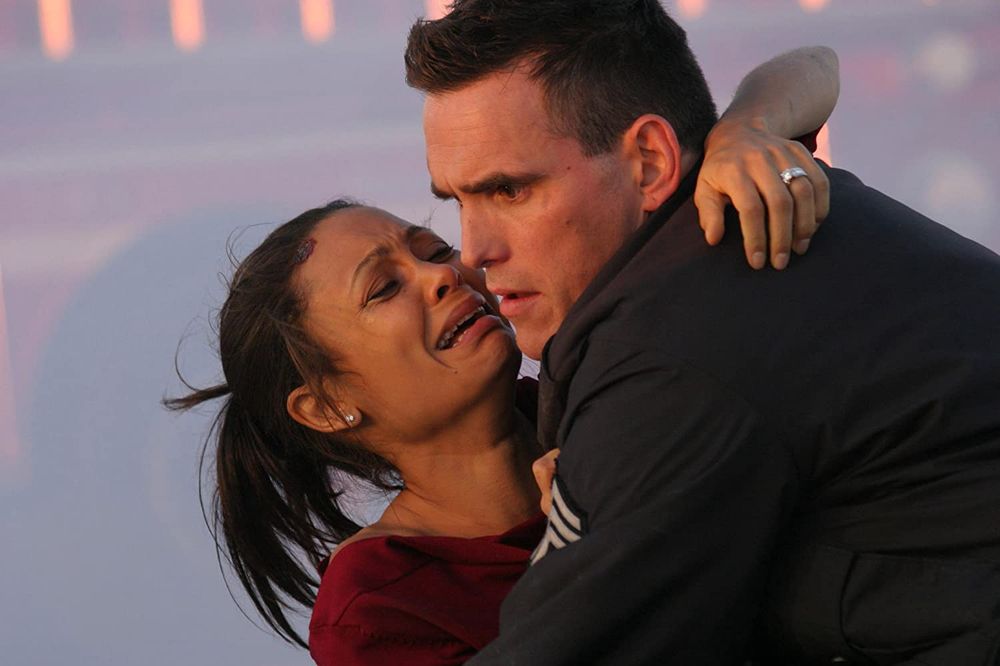

Shortly after that deeply moving scene, with no sign of actual growth in sight, Officer Ryan encounters Christine once again; this time, she’s trapped in an upturned car that’s on the verge of exploding. (It’s only one of an exhausting complement of car accidents in the film — because, you know, crash.) His very presence presents her with a choice: perish in the wreckage, or escape by embracing the man who abused her only days earlier.

Haggis’ slow-motion extension draws out the carnage: of Ryan jumping into the car and saving her; Ryan looking shocked that he could actually care for a Negro; Christine wailing dramatically. The visual of the unlikely pair — forced together once more by fate — would make Loving v. Virginia Twitter jump for joy. I’ve seen TikTok videos with more subtlety.

There seemed to be a real catharsis in this moment for Officer Ryan’s real-life counterparts: all those would-be White saviors held back only by their own disenchantment. Critics and award committees adored Dillon’s performance. No knock on the man’s acting — he plays the asshole role well — but I can’t help but think that for a drawn out, overdramatized depiction of a problematic pig, what actually got him the plaudits was the idea of a cop just doing his job for once.

Crash leaves so much room for White people to feel safe in their ain’t-shitness, it should be watched as a comedy. It projects post-9/11 fears and paranoia back upon Brown folks. It displays Black people as smart enough to notice our stereotypes but crass enough to luxuriate within them. But for some reason it only takes Sandra Bullock’s character a sprained ankle to realize that she’s an angry-ass racist White woman and begin to change her ways? The grace Haggis bestows White people who have otherwise shown zero potential for growth isn’t just troubling, it’s… well, it’s almost as if this film is a wee bit racist.

In the Folks Should Know Better Era —anything after Birth of a Damn Nation — the key diagnostic in such evaluations is to peep how Black women are portrayed and treated. And it’s here that Haggis’ disdain is laid bare. Granted, given the sexual assault allegations he faced in recent years, it might come as little surprise that Haggis has a problem with women. But the full depth of it can be found right here in Crash.

Given the hunger we felt for onscreen representation in 2005, it was (and is) easy to get distracted by all the colorful faces, but Crash manages to be one of those movies where literally every character is trash but only White characters evolve. And the truth is, that’s instructive. I remember studying the hell outta this film as a teenager largely because of its simplicity, and how easy and comfortable it made cultural harmony seem. Crash places the burden of such harmony on non-White people, and — more violently — on Black women. That may reflect life in the most brutal ways, but against the starkness of its White-redemption backdrop, it exposes itself as the exact opposite of the progressive “kumbauya” it was intended to be.

I came into this rewatch with a simple question: Is Crash a racist film? Now, I can answer it unequivocally.

You bet your Black ass it is.