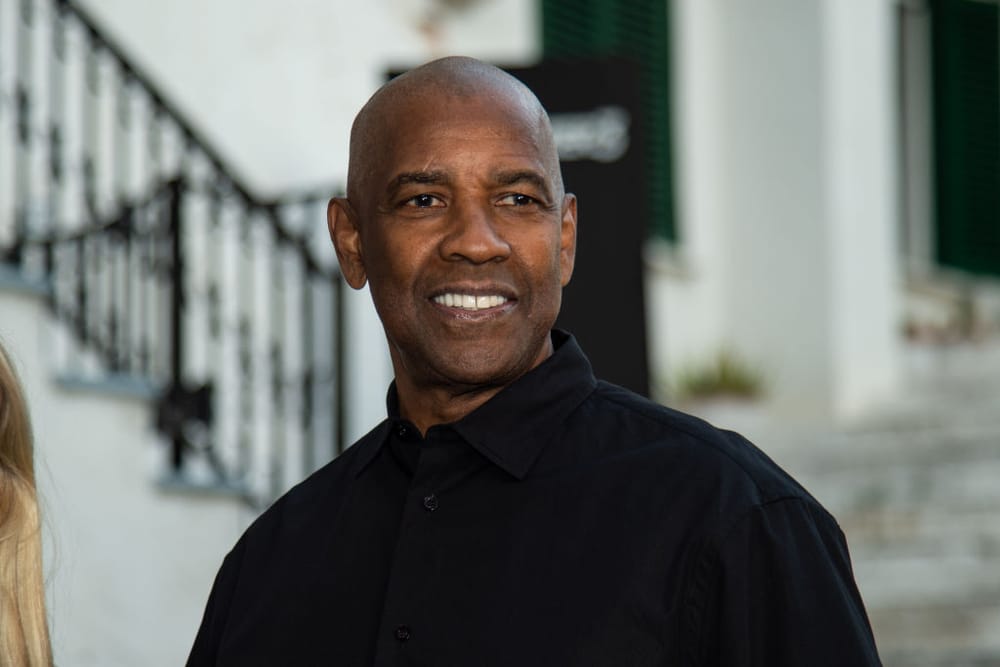

Is Denzel Washington the best actor who has appeared in the largest number of bad movies? Bad, of course, doesn’t mean unwatchable. Denzel doesn't do, junk cinema. But bad isn’t good, and as someone who has bought a ticket to every one of his movies for decades, I’ve always found it difficult to reconcile my affection for the man with my disinterest in the movies that maintain his stardom.

I’m not talking about Malcolm X (1992), Spike Lee’s masterful biopic that should have won him the Best Actor Oscar, nor am I talking about the occasional prestigious awards bait he attaches himself to, like Fences (2016) or The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021). These movies, despite critical praise, never made much of a splash at the box office anyway.

No, I’m talking about the other, dirtier Denzel movies. The ones that people actually show up for on opening weekend. The ones in which he is often carrying a gun, or a badge, or sometimes both. The ones rooted in disreputable genres, like the revenge thriller. The ones we’ve all seen numerous times while scrolling through cable on a lazy Tuesday, and although we know that we should spend our evening more productively, perhaps with TCM, we can’t help but keep the channel on TNT and watch Denzel…in anything. We promise our partners just one scene, but before we know it, we’ve gone and finished the whole damn movie, commercials included, just to witness Denzel do what he does best, and what no one else in Hollywood can match.

And man, that thing he does! Denzel takes mediocre movies and makes them matter just by being in them, which is the true definition of a star. Predictable and preposterous, the movies Denzel regularly headlines are the definition of disposable trash. In the 21st century alone, he has given us garbage hits like John Q (2002), Man on Fire (2004), Deja Vu (2006), The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009), The Book of Eli (2010) Safe House (2012), Two Guns (2013), The Magnificent Seven (2016), The Little Things (2021), and his only franchise, The Equalizer (2014), The Equalizer 2 (2018), and The Equalizer 3 (2013), each installment sillier than the last. And if you think Denzel’s output from the 1990s only consists of classic Spike joints, you aren’t remembering Virtuosity (1995), Courage Under Fire (1996), Fallen (1998), and The Bone Collector (1999), mid-budget genre flicks he made after Malcolm X, all of them synonymous with schlock.

Now, some of these titles are less mediocre than others, but none of them are great. They are serviceable entertainments at best, and yet, I’ve seen every single one because I love watching Denzel smile and talk his way out of a problem. I love watching him walk with a swagger, seduce a pretty woman (particularly Paula Patton), and perform pulp with the same intensity as Shakespeare. He makes it look so easy, but it isn’t. Just ask Liam Neeson.

In these movies, Denzel often plays a flawed everyman who is placed in dangerous situations that force him to overcome his inner demons and save the day. There’s usually a mistake from his past that haunts him or an unresolved obstacle from the present that threatens to overwhelm him, and the plot of the movie provides him with a chance at redemption. He seizes it by putting his life on the line. By the end, justice is restored and he can rest peacefully. That is, until the next Denzel movie, when he must once again Dad up and take the call that no one else will.

Over the past few years, critics have argued that Tom Cruise’s latest action movies are meta reflections of the star’s resilience, the idea that his contemporaries in Hollywood haven’t succeeded as he has, with such stamina and staying power. These critics haven’t been paying attention to Denzel and his disposable movie canon, which is just as reliable and relevant now as it was over twenty years ago when he turned Training Day (2001), a glorified exploitation movie, into an awards contender. The surprising box office success of The Equalizer 3 confirms this. The movie received middling reviews, but it over-performed on opening weekend, drawing in audiences of all ages and demographics. People knew what they were paying for — the chance to see Denzel sit in an Italian cafe and take down the mafia — and they happily showed up for it. In its quiet way, the success of The Equalizer 3 is the most impressive industry story of last summer, especially when compared to Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, two tent poles with bigger budgets that struggled at the box office, despite Cruise and Harrison Ford.

The Equalizer franchise is a fascinating late career flex, but the movie at the center of Denzel’s disposable movie canon is Man on Fire, a hyper-stylized revenge epic directed by Tony Scott that, since its release in 2004, has become a cult classic. It contains all the essentials moviegoers expect. The plot, which hinges on an abduction, is simple to follow and too foolish to believe. Denzel plays a brooding ex-CIA operative unable to forgive himself for past on-the-job failures, with a little bit of alcoholism thrown in to intensify the despair. The daughter (Dakota Fanning) of a wealthy businessman (Marc Anthony) is placed in his care and presents him with an opportunity to prove himself worthy of forgiveness. When criminals kidnap the daughter, he races against time to track them down, killing those who stand in his path. For good measure, in case you assumed this was a serious drama, the movie contains a scene of Denzel shoving a bomb up a villain’s ass.

How does this guy top The New York Times list of 25 Greatest Actors of the 21st Century, ahead of Isabelle Huppert and Daniel Day-Lewis? It may be tempting to dismiss Denzel’s disposable movie canon and focus solely on his respectable fare, but such an appraisal would be incomplete. A.O. Scott, who created the list with Manohla Dargis, offers an alternative take. “Maybe one measure of his mightiness is how consistently he’s better than the movies he’s in,” Scott posits.

Scott is correct, but plenty of actors elevate lousy material, and unlike Denzel, they haven’t received two Academy Awards, the AFI Life Achievement Award, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, among other top honors. Denzel is the rare respected actor whose acclaimed work doesn’t represent the majority of his filmography. His average Metacritic score is 64, which seems accurate, but also wildly low for someone considered a titan. Still, there’s something about Denzel and his disposable movies that can’t be denied, and given how many he’s made, it’s fair to say that he’s built such a noted reputation because of the duds, not despite them.

What, then, makes Denzel stand apart from the countless other wannabe stars whose careers are similarly rife with second-rate dreck? More significant than, say, Neeson or Bruce Willis or Sylvester Stallone or Arnold Schwarzenegger or Mel Gibson? Maybe, unlike those other guys, it has to do with the image of the star off the screen. To many, Denzel’s movies mean a lot less than the man himself and how they perceive his place in the world.

Denzel doesn’t seem pretentious. Despite being a famous millionaire, he presents himself as an ordinary family man, someone of deep faith (“God is good,” he quipped after winning his second Oscar), and perhaps most relatable, a guy who just gets up and goes to work every morning, scandal-free. When asked about his breakfast routine, he once said, “I like a simple breakfast, a little diner, with bacon and eggs and hash browns, some real good greasy funky hash browns, a little OJ, a cup of coffee, I’m good.” A cynic might compare his response to a politician’s, but it aligns him with us.

Unlike most celebrities, Denzel never mugs for the camera off the set, preferring to keep his private life a mystery. When a reporter asked about his political views, for example, he famously said, “That’s none of your business” before shining those pearly whites, a disarming and polite shutdown only he can pull off. In another instance, he said he would have to be “more informed,” a rare humility that is infectious. If only others in Hollywood would follow suit.

The off-screen persona Denzel has constructed — of an average family man who works hard to stay on the path of righteousness and achieve success — bleeds into the many working-class characters he plays to the point where we believe we are watching him. And because we admire him so much, we’re willing to accept the barely passable movies he chooses. We just want to see him in action, however idiotic the plot is.

To a certain extent, this is Movie Stardom 101, but it’s also something more. After all, Cruise earns our praise for his commitment to the craft (those stunts!), but few people would want to be associated with him personally, given his uncomfortable support of Scientology. The same can be said of Clint Eastwood, a cinema icon Denzel is often compared to, whose appearance at the Republican National Convention in 2012 turned off many casual moviegoers. A defensive tone set in: We’re here for Clint’s movies, not the man. But with Denzel, there’s no distancing. We love the man most of all, or at least, the man we think we know. That’s why we continue to show up.

One evening last year, I had some free time to myself and, as is often the case, I wanted to see a movie. Living in New York, I had many options to choose from. A restoration of a Jean-Luc Godard classic, Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967) in 70mm, and an overlooked gem from Korea’s golden age. Against my better judgment, I went with The Equalizer 3. As I found my seat and the lights went down, I braced myself for the stupidity to come. Like everything in Denzel’s disposable movie canon, it was terrible and glorious. The scary bad guys threatened disorder, but there he was, as big as I remembered him to be, telling me that it was going to be okay. With him in charge, it always is.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium.