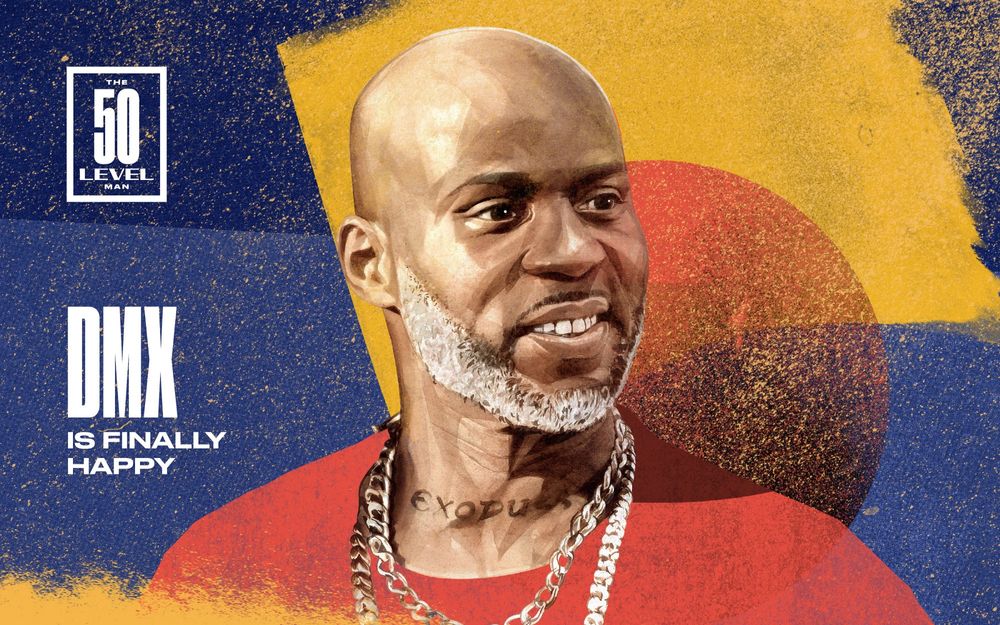

We always rooted for Earl Simmons — but seeing his joy as he turns 50 has helped us find our own

Tonia Colon-Seals wasn’t sure what to expect when a guy named Earl showed up at her door in Lithonia, Georgia, in the winter of 1997 wearing a red flight jacket, jeans, and a pair of Timbs. All she knew was that he was a rapper, and her friends Joaquin and Darrin Dean (Waah and Dee), brothers who ran a management company in New York, had sent him down south to stay out of trouble while he finished his debut album.

The album, of course, would be a multiplatinum behemoth; It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot snatched hip-hop out of the awkward limbo that had followed the killings of Tupac and Biggie, launching DMX into the stratosphere as one of rap’s most marketable names ever and turning the Deans’ Ruff Ryders into a juggernaut record label. Nobody in Earl Simmons’ circle knew this would happen, of course. All they knew was that X was, by his own accord, a dog off the leash, and if he kept up at his current pace, he wouldn’t live long enough to see his album’s release date. That’s where Tonia Colon-Seals came in.

The Colon-Seals home had become a halfway house of sorts where rappers would go to finish their projects away from distractions and any chances of running afoul of the law. DMX would turn out to be the biggest star to come out of the residency — but at the time, he was the one who worried everyone the most. Tonia heard the warnings and concern, but she knew she could reach the troubled MC through tough love, scripture, and modeling what a family structure could look like.

“Everybody always looks at him as reckless,” says Colon-Seals on a Zoom call while looking for a signed It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot plaque DMX gave her for her 50th birthday some years ago. “No, he’s not reckless. He was looking for direction.”

While X was hesitant at first, he would eventually open up to the woman who reminded him so much of his grandmother. And Tonia would come to know a DMX that the rest of us just are getting to meet for the first time: One who’s happy to be alive, who’s legitimately joyful, and who’s keeping at bay the demons that threatened to swallow him whole.

In that Georgia home, DMX huddled around the dinner table with Tonia and her young children, eating arroz con pollo. He played board games with them, talking trash while trying to build hotels on Monopoly properties. He read scripture. He prayed. He practiced salsa dancing. “He used that terminology [of himself] as a dog because he felt he was always out of control,” Colon-Seals says. “I didn’t want him to think that somebody has to tame him and train him. No person has that power but the almighty himself.”

Trying to envision DMX trying to land on Boardwalk, let alone cutting a rug, isn’t easy. DMX does normal stuff? It would be a bizarre concept for anyone who’s ever heard his music or seen an interview with the man. The DMX persona is, by all accounts, Earl Simmons turned up to the maximum, like a pro wrestler who turns his charisma to captivating catchphrases and rabid fan bases. The rapper brought us into the world of Dark Man X. His depression, abuse, and spirituality, his sins and his blessings. We ate it up, devoured his story as our own.

His entire catalog has been about death approaching. His headlines over the past 15 or so years — arrests, addiction, instability — have echoed the same. But now, the rest of us are seeing a DMX that only a few knew existed. It’s a blessing we didn’t know we needed.

For me, a 12-year-old kid whose parents had divorced just months before It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot was released, DMX represented the antithesis of Diddy and his shiny world — a world that felt diametrically opposed to mine. DMX was the rage I wanted to let out. While rappers were getting jiggy and flashing jewelry, DMX was releasing gritty, black-and-white videos and stick-up anthems like “Stop Being Greedy.” The “Damien” trilogy from his first three albums was all about proximity to the devil and trying to claw himself to humanity. He’d end his albums with prayer, a hope and a hint that the darkness was always lurking. I felt these stories as my own. I became captivated by the sage of DMX, even outside of music.

I wasn’t alone. An entire generation became engulfed in the DMX saga of redemption, pitfalls, and volatility. So much so, in fact, that we lost sight of Earl Simmons, the regular guy who was hidden from plain sight.

That’s why this new DMX, who just turned 50 in December, has been so jarring. And so welcomed. His entire catalog has been about death approaching. His headlines over the past 15 or so years — arrests, addiction, instability — have echoed the same. But now, the rest of us are seeing a DMX we never knew existed. It’s a blessing we didn’t know we needed.

In April 2020, a little more than a year after leaving federal prison, DMX appeared out of nowhere, delivering virtual Bible study sessions on Instagram and setting in motion the dream of being a preacher that he’d rapped about for two decades. “It’s God’s will,” he said in one of them. “It’s always God’s will. If you try to understand why he does what he does, you’re going to wind up with a headache.” These weren’t schtick. They were legitimately inspirational sermons from someone with an intimate understanding of the Word. In the middle of the most volatile year of our lives, we found ourselves seeking stability from someone we’d once seen as an archetype of chaos.

But what leaped out even more than the sermon was how DMX looked. He looked like he’d put on weight. His eyes looked clear. He was… smiling. DMX looked healthy. Outward appearances can betray reality, of course, but seeing this version of X felt cathartic in its own right. If he could find a light, we realized, then anything was possible, even in our darkest collective moment.

“I see him happy when he does a prayer,” says Ruff Ryders co-founder Darrin “Dee” Dean, who has known DMX since the ’90s. “Those types of songs and moments make him happy. He’s that type of brother who shows love to the people he feels need love. You feel like God put him here to help the people.”

The thing is, we always knew DMX wanted to preach. This development was where his public life had always pointed — at least, it was the version we’d hoped for. It was the other stuff that took us by surprise.

When DMX headlined a July Verzuz battle with Snoop, he was a whole different person. He was two-stepping. He was smiling, cracking jokes, and dancing like he was in a living room in Georgia. The two-hour broadcast felt like a revelation. A coming out party. Suddenly Dancing DMX became a viral craze. “DMX dancing to cleanse the timeline” became a common refrain on social media as he danced to his own songs or ’80s R&B. Simmons’ joy helped us find our own.

DMX has always been one of the most vulnerable artists of our generation, unafraid to cry while praying on stage or detailing the worst moments of his life. But the vulnerability it takes to show pain is different than the kind that allows one to show happiness. To allow oneself the space to enjoy life. To bask in the glory of a smile. We’d seen the unguardedness of his pain and appreciated him for it. But the freedom he gave himself to be happy is a gift that has felt even more fruitful.

It’s impossible to know how long this happy DMX will last, no matter what we want for him. There’s always worry that the crash is around the corner. Which is another reason this moment is so precious. For someone who rapped about death at his front door and his preoccupation with the end, simply seeing DMX hit his sixth decade feels like a miracle. “It wasn’t a guarantee that he was going to make it to 50 the way he was running at a certain point in his life,” says Dean. “So for him to still be here is a blessing. And I guess God’s looking over us.”

But seeing him happy at 50? That feels like a defiance of odds beyond our wildest imaginations.