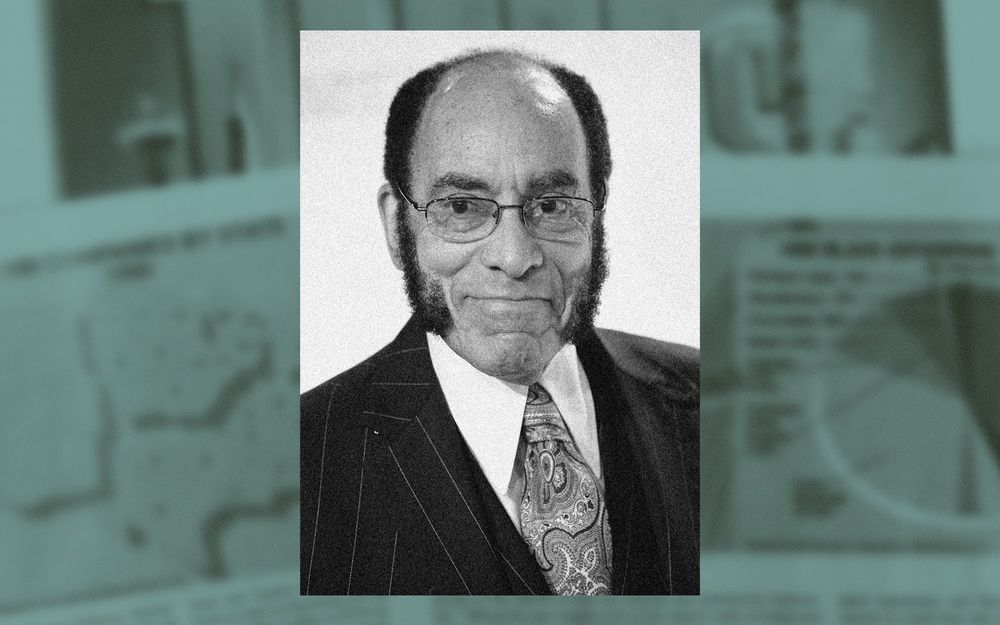

Earl Graves Sr. had a presence.

At nearly 6 feet 4 inches, Graves often dominated the rooms he entered. It wasn’t just his height that commanded respect or his signature sideburns; what made the man truly legendary was his vision. Over his 85 years, the Black Enterprise founder created an ecosystem of business empowerment, and in the process made himself synonymous with the audacity of Black entrepreneurs.

It is no understatement to say that Graves was one of the first entrepreneurs — certainly Black entrepreneurs — who embodied the ethos and aspirations of his own brand. Decades before today’s brand leaders in fashion, music, and sports leveraged their personas into market share, Graves perfected the blueprint. In the ’80s, Jordan became Brand Jordan. In the ’90s, Diddy wore jerseys emblazoned with Bad Boy. But long before that, Graves’ three-piece suits, monogrammed cuff links, full Windsor knot, and wingtip shoes were associated with his empire.

Before he started Black Enterprise, Graves worked in Sen. Robert Kennedy’s office, serving with him from 1965 until the senator’s assassination in 1968. In 1970, only two years after the assassinations of Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., Graves set out on his own to launch a publication celebrating Black businesses and entrepreneurs breaking barriers, creating jobs, and building wealth in our community. Black Enterprise launched with a $175,000 loan; it had turned a profit by the 10th issue and would go on to reach a peak circulation of 500,000 in the ’90s.

Graves’ secret? He believed in Black people. Graves’ success stemmed in large part from his own version of the “five forces” business theory framework. Popularized by Harvard professor Michael Porter in 1979, the model teaches entrepreneurs and executives to make informed decisions by looking at the relationship between five areas: rivals, suppliers, cost of entry, potential substitutes, and key customers. By critically analyzing industries, this framework identifies opportunities and challenges to be mastered to not only survive but to thrive.

In the ‘80s, Jordan became Brand Jordan. In the ‘90s, Diddy wore jerseys emblazoned with Bad Boy. But long before that, Graves’ three-piece suits, monogrammed cufflinks, full Windsor knot, and wingtip shoes were associated with his empire.

Graves was his own force. If you review his life and his work, you will see that he created his own five forces model, nine years before it was widely taught at business schools.

Belief in entrepreneurs

Graves was the undisputed champion of Black business in this country. Supporting and developing Black businesses has been a hallmark of his storied career — including his own. The idea of rivals was antithetical to his mission.

While Graves had complete market dominance of Black business publications, it never stopped him from making sure the entrepreneurs he featured in the magazines — and those who hoped to be — were in the same circles. Early in my career as president and CEO of Vibe magazine, Graves embraced and acted as a mentor in the world of Black media.

Today there are more than 2.6 million Black-owned businesses in the United States. Notably, in the 21st century, Black women have been at the vanguard of entrepreneurship. Of the 2.6 million Black businesses today, 1.5 million are female-owned. Nine out of 10 Black-owned businesses are sole proprietorships. This is what Black business looks like today. Does this mean every business has Graves and Black Enterprise to thank? Not necessarily. But he undoubtedly paved the way. There was no need for rivals when all had a seat at the table.

Promoting executives

For Black businesses to thrive, they have to become vital trading partners with and key suppliers to Fortune 500s and successful private companies. This means fair opportunities to compete for contracts and new ventures. Black Enterprise made sure we learned about pioneering Black executives of extraordinary achievement, like Kenneth Chenault of American Express and Ursula Burns of Xerox. Graves showed us what Black corporate excellence looked like, which no doubt inspired the next generation of executives like Thasunda Brown Duckett, CEO of Chase’s consumer banking business. He knew that to fuel Black business you had to have successful Black corporate executives. Without Black corporate executives, there is less access and opportunity for Black businesses. Without successful Black corporate executives to emulate, young Black professionals lack mentors and sponsors. Period. That information was found in the pages of Black Enterprise every single month.

Business, policy, and politics

For Black entrepreneurs, the cost of entry has often been tied to skin color. In the early days of Black Enterprise, the road to the C-suite was mysterious. Deals were often made in country clubs that didn’t accept people of color. (And likely, still are, in some spaces.) Graves dropped that cost of entry to zero. He made sure that his writers always had their ears to the streets and covered Black entrepreneurs from those distilling new ideas to those preparing for their IPO — and far beyond.

Corporations need accountability and governance. Black elected officials, policymakers, and civic leaders hold corporations accountable for Black hiring and equitable supplier distribution to minority businesses. When PepsiCo asked Graves to help them reach the African American community as partners and suppliers, he created the PepsiCo African American Advisory Board, which included the Rev. Al Sharpton among a host of leading civic and business leaders. Graves’ philosophy is just as relevant today — his son, Earl Graves Jr., interviewed Donna Brazile at the last Black Enterprise Women of Power Summit.

Industry knowledge

Graves and his team always believed in nimbleness and the ability to pivot. He started out handing out free issues of Black Enterprise to potential subjects and advertising clients. When sales of the print issue began to slow in the internet era, Black Enterprise had already bolstered a digital presence — and that presence remains strong today, with longtime tentpoles like the BE 100s moving to the web.

An advocate of education as well as hands-on exposure to business, Graves was a longtime champion of corporate internship opportunities. Graves understood that just as Black businesses are essential, so too are historically Black colleges and universities. Today, HBCUs produce four of every 10 Black college graduates in the United States. These students, future entrepreneurs, and executives are the talent pipeline our nation needs to remain competitive in the global economy. In recognition of his lifetime commitment to paving the way for future generations, Morgan State University named its business school the Earl G. Graves School of Business & Management.

Key customers

This one was always easy for Graves: He was the key customer. As long as he remained true to his own vision as a business owner, the magazine itself would do the same. He also made a point to bring his three sons into the family business; they were both customers and consumers as well. Graves knew that a family business (his wife Barbara Kydd Graves, who passed in 2012, was on board from day one) is a business that has a fighting chance to remain viable. His son Earl Graves Jr. is at the helm and ready to continue his father’s legacy.

During his upbringing, his military service, and his time in government, Graves observed that successful people network. They find ways to work together. They find ways to build each other up. This principle inspired Black Enterprise’s events. Network, network, network. But the lesson that he leaves is that networking is as much for the next generation as it is for self-advancement. To sustain our Black economy, we have to give our young people access.

For decades, Black Enterprise fueled the dreams of young entrepreneurs and professionals long before social media existed. Graves did more than chronicle successful Black businesspeople — he created a blueprint for brand-building in a multimedia world.

Black people matter. Black businesses matter. Black entrepreneurs and Black executives matter. Before we realized we needed it, Graves showed us that Black Enterprise matters.