I was 22 when Drake’s defining, star-making mixtape So Far Gone hit the internet like a meteor. At 22 years old, swarming Mediafire and Rapidshare links like they were electronics stores on Black Friday morning, looking for the one that still had what I was after. Just 22 years, ringing in Valentine’s Day 2009 in my car, driving around Chicago, listening to So Far Gone. Alone.

I was a year into my career as a music journalist, watching the internet wreaking absolute chaos on the industry. Stars like Wiz Khalifa and B.o.B had already emerged from the new ecosystem, dropping projects online and circumventing the gatekeepers entirely — but we were all still waiting for that one crossover artist for vindication. Someone to prove that the future was online. Someone who could go directly from Datpiff to a household name.

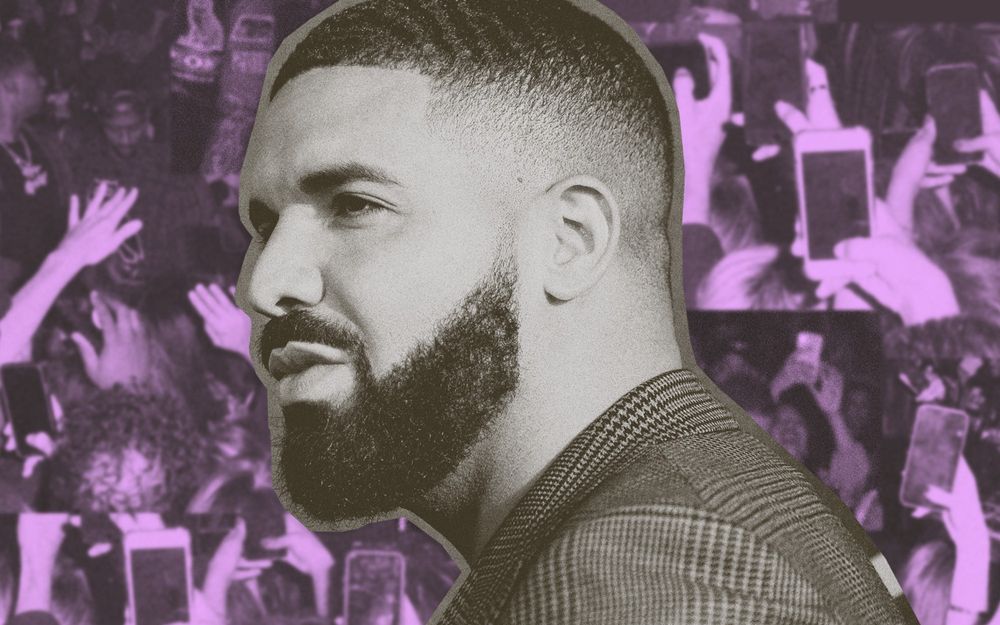

Drake was that messiah, and So Far Gone was that gospel. The album spawned a tour, music videos, Billboard-charting singles. But most importantly, it first showcased the Canadian child actor’s most persistent gift: His ability to tap into and articulate a cultural shift, to make it resonate so loudly that it drowns out everything else. Drake, just six months my junior, was speaking directly to a young twentysomething in the jaws of a once-in-a-lifetime capital-R recession who was balancing hopes and dreams with the prospect of being an unending failure.

He’s a one-man boardroom, assessing the musical and cultural landscape and then building his gleaming high-rise smack in the middle of the hot neighborhood, towering over everyone else’s developments.

In one moment, he’s pleading that “I just wanna be successful”; in another, he’s talking about disappointing his mother while struggling with money (“…she wonder where my mind is, accounts in the minus”). You want angst? “Say What’s Real,” a four-minute rumination on loneliness and broken promises over a beat from 808s and Heartbreaks, starts with the kind of phrase you’d find written in any emo kid’s journal: “Why do I feel so alone?”

And I felt that s**t. I drove around that Valentine’s Day Eve, breathing in the skyline, wondering at the way he had given voice to the anxiousness, hopes, fears, dreams, and insecurity roiling inside me.

Yet, a decade later, I can’t find a single Drake lyric that I can relate to. When I listen to Drake — and I do — I hear someone who is still speaking to 22-year-old kids, and my connection to it is fleeting at best. There’s surprise in that, and sadness, and maybe some guilt. But there are questions too. Why have I moved on? Why hasn’t he?

Is it even fair to ask an artist to move with me?

2020 doesn’t feel that different than 2009. We’re somehow back in a once-in-a-lifetime, capital-R recession. I’m still worried about disappointing people who depend on me. But this time, it’s a wife and kids. This time, the prospect of failure is falling behind on my mortgage. This time, I fear the collapse of the world outside my own hopes and dreams.

And Drake is making TikTok dances.

Don’t hear that as more cynical than it is. In 2020, Toronto’s favorite son has become the biggest non-producer hitmaker ever. He’s Michael Jackson, The Beatles, and Taylor Swift rolled into a single artist who has mastered the most popular musical genre on the planet. He was the most-streamed artist of the 2010s, and has more No. 1 songs than the King of Pop himself. You could probably count on one hand how many artists could stand up to Drake in one of those Instagram Live Versuz battles. Ever. His ability to manufacture a hit seems effortless in the same way that LeBron James notching a triple-double seems effortless.

Drake has embraced superstardom while avoiding infusing his music with anything that feels real. His self-reflection is all platitudes and performance art, acting like vulnerability while keeping the truth at arm’s length.

Even the recently released Dark Lane Demo Tapes — a collection of B-sides and previously released loosies — is a 28-point, 12-rebound, 10-assist game. Every song sounds like a hit; I’m humming along to “Time Flies” as I type this. Virtually the moment the project came out on Friday night, Twitter timelines were inundated with people quoting catchphrases and hooks.

That second-screen phenomenon isn’t new, long having been a Cliffsnotes-style instantaneous companion to any new Drake song. He seemingly burps out phrases that are instant Instagram captions, slogans that immediately make a home on the tips of tongues across the world. YOLO. Nice for what. No new friends. God’s plan. Proctor and Gamble would kill for this amount of IP, and it’s the tiniest fraction of dude’s curriculum vitae. Dark Lane Demo Tapes is no different. It’s meme music. Search-engine-optimized bars. Baby Yoda music expertly curated for the most engagement.

Creatively, Drake’s not operating at the same level as an OutKast, Kendrick Lamar, or Kanye West, dreaming up new genres of music or unearthing never-before-heard avenues for his art. That’s not a knock. That sort of boundary-pushing isn’t everyone’s ministry, nor is it a prerequisite for greatness. Drake is an executor — or, more aptly, an executive. He’s a one-man boardroom, assessing the musical and cultural landscape and then building his gleaming high-rise smack in the middle of the hot neighborhood, towering over everyone else’s developments.

He’s done this his whole career.

When Phonte used a singer/rapper hybrid to create an everyman persona, Drake made that aesthetic mainstream. When Big Sean utilized a new flow on “Supa Dupa,” Drake used the same pattern to hold his own alongside megastars Eminem, Lil Wayne, and Ye on “Forever.” When he tapped into afrobeats and dancehall, “One Dance” stayed at the top of the Billboard Hot 100 for 10 weeks. In recent years, he’s adopted British grime as his musical influence of choice — all the while exhibiting an unerring knack for identifying emerging artists and creating new waves based on their sound. Migos; The Weeknd; BlocBoy JB; ILoveMakonnen. To some, that’s borrowing, even stealing. To others, it’s perfecting.

That happened all over again with his TikTok “Toosie Slide” challenge. The man sat in his house, conjured up an undeniably catchy song like some harmonizing wizard, shot a homemade video, and has now broken the record for the fastest TikTok to reach 3 billion streams. (And snagged his umpteenth No. 1 hit in the process.) There’s Drake again, tapping into a cultural moment and planting his flag right at the center. This time the moment is a society that’s isolated and desperate for entertainment while embracing a new social media landscape. How do artists entertain? How do fans want to be entertained? The answer is always Drake.

Generally, TikTok is still immune to brands and consultants social-engineering their way to virality. If something spreads wildly on the platform, it’s authentic. Crazes are built by 14-year-old Black girls like Jalaiah Harmon, who danced to a K Camp song she liked and took it all the way to the NBA All-Star Game and turned it into the “Renegade Challenge.” (But not before other folks began taking credit for it.) “Toosie Slide” is the antithesis of that authenticity. It feels like it was created in a focus group. It’s KFC making hot chicken sandwiches. It’s Starbucks moving next door to your favorite independent coffee shop. But through sheer force of star power and inertia, Drake manages to escape the resentment that corporate invasions usually invite. There isn’t another thirtysomething, perhaps in all of entertainment, who could pull off such a move.

The 22-year-old me thought Drake would be along with me for the ride, creating the music for my generation as my generation got older. I wanted him to leave that car in Chicago with me and walk with me through my first jobs, marriage, kids, and stress. Drake has embraced superstardom while avoiding infusing his music with anything that feels real. His self-reflection is all platitudes and performance art, acting like vulnerability while keeping the truth at arm’s length. It’s music that kids eat up but people my age can see right through.

I think Drake knows this. I don’t think he cares. He doesn’t make the songs for me to enjoy. He makes them for me to hear at every party, on every cellphone, on every twentysomething’s IG page. He makes lyrics for me to repeat — not for me to feel.

Like me, Drake is a father now. Unlike me, though, he’s grappling with a fatherhood that’s not the one he visualized: Growing up wanting a nuclear family, only to have a baby momma he has to send child support payments to while setting up a visitation schedule. It’s an unexpected chapter of a book that started with him contemplating marriage in his early twenties, even before it was something I was ever considering. Drake, the hopeless romantic who was unafraid to put those emotions at the forefront while rappers were still getting made fun of for it (“Yeah, wanna grant one of my wishes, Tired of missing you, I’m tryna make you a missus,” he rapped on his early Comeback Season mixtape) is now a baby daddy.

Drake has positioned himself as someone who deserves to be discussed among rap’s all-time greats. If that’s the career trajectory he wants to have, then it’s fair to ask him to push himself to more substantive greatness.

Maybe that’s why “March 14,” the last song on his last real album, is one of the only times in the last few years I’ve felt connected to Drake’s music:

"It’s breakin’ my spirit/Single father, I hate when I hear it/I used to challenge my parents on every album/Now I’m embarrassed to tell ’em I ended up as a co-parent/Always promised the family unit/I wanted it to be different because I’ve been through it/But this is the harsh truth now"

It’s an honesty and vulnerability that I missed. An emotional depth from Drake that’s far too rare. Yet, he was forcefully pushed to this honesty after rival rapper Pusha-T revealed the existence of Drake’s son to the world during their flurry of diss records — and the candor was fleeting. Earlier this year, he went back to his facade, calling the mother of his child a “fluke” on his loosie track “When To Say When.” The sentiment isn’t crass as much as it is inauthentic. It’s posturing, yet another performance of Not Giving a F**k when he really cares. (“If I f*cked her once I never f**ked again,” he said on 2012’s “No Lie,” hinting about Rihanna to betray the fact he was clearly emotionally invested in that relationship.)

That performance plays both ways. There’s a moment at the end of “Summer Games” — a minimalist faux techno ballad that sounds like it should be played in an Express dressing room — that has a bridge of Drake just repeating “breaking my heart” a dozen times. The vapidity of it is astonishing. The emotional detachment it takes to do that instead of saying anything more substantial (literally anything) is a Drake staple. I might have liked it at 22. Drake might have made that at 22. To be making that a decade later is arrested development.

Drake is well within his rights, obviously, to continue making simple-carb hits while solidifying himself as the most prolific hitmaker to have ever lived. But that all depends on where The Boy envisions himself in the annals of greatness. There are two clear paths he can take from here — and they could even overlap if he manages to walk the gossamer tightrope the greatest artists tiptoe across. He can be an automatic chart-topper, Nelly with longevity. He’ll be respected. He’ll be appreciated. And he’ll always have a song playing at any given moment for the rest of time.

But Drake has positioned himself as someone who deserves to be discussed among rap’s all-time greats. He’s come at Jay-Z’s neck, in 2010 adding “your idols become your rivals” to his repertoire of Instagrammable lyrics. He’s battled Common and Meek Mill. He’s traded subliminal disses with Kendrick Lamar over who’s the rap alpha dog. If that’s the career trajectory he wants to have, then it’s fair to ask him to evolve into someone who pushes himself to more substantive greatness.

Beyoncé started her career as a late teen singing about what man is going to pay her bills. She became an early-twentysomething singing about her body being bootylicious. She could continue making variations of “Dangerously In Love” for decades, but she evolved into a deified entity by making something more. Music about pain, radical Black love, and the power of Black women.

Jay-Z gave us The Blueprint at 31 and The Black Album at 33, two albums wholly concerned with his legacy and moving beyond the drug-dealer raps that made him viable. Kanye West made a hard left turn at age 31 when he dropped 808s And Heartbreaks; the Auto-Tuned full-length was immediately polarizing upon release, but aged like Angela Bassett. Lil Wayne has been in a constant state of reinvention for the past decade, using last year’s Tha Carter V to grapple with mental health. (Even Drake’s former rival Meek Mill is tackling PTSD and the criminal justice system.) Meanwhile, Kendrick Lamar is pushing himself sonically, making each album sound different than the one before it.

This is Mount Rushmore stuff. If Drake wants to be among those faces, he has to find out when and what evolution looks like for himself.

Drake was my musical guiding light when I was 22. He’s spent the last decade as a revolving door, making the defining music for each new class of 22-year-olds. He’s long stopped making music for me, and that’s been a deliberate choice. Maybe I’m the fool here, wanting an artist to be something he’s not. When I hear a new Drake song, I know that he’s not making it with me — or anyone else my age — in mind. But one day that revolving door will start to creak. The glass will get dusty, cracks spidering in from the edges. It’ll get stuck, and kids will find it too old to even bother with anymore. Where does Drake go then? Who does he talk to? Who does he speak for?

Drake, the musical and pop culture mastermind, may have this all figured out. It’s quite possible he’s already charted his next steps and knows when to pivot to the next moment. It’s quite possible nothing I’m saying here is new to him. He may already be focused on the new chapter of his career that fulfills the promises he made when he cracked the music industry’s surface in 2009. I cling to the idea that I’ll hear his music again one day and engulf myself in the lyrics, connecting to every syllable.

Until then, I’ll just have to settle for humming along with his hits while watching him break endless records — all the while waiting to see what’s next, watching everything fall in line according to Drake’s plan.