In a Brooklyn bar one night, a bestselling author called me a Beytheist. A Beyoncé atheist, a nonbeliever. The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour had touched down at the Barclays Center that evening, and the BK crew wanted to know what I thought of the concert. Michael Jackson wowed me at Madison Square Garden in high school; Janet’s theatrics, pyrotechnics, and killer choreography blew me away through four different performances in the ’90s; Madonna’s Girlie Show tour, too. I said that Beyoncé fit in that tradition, but anything less than “Beyoncé is God” fell on deaf ears. I’d blasphemed and been excommunicated. I think the Beyologian (Beyoncé theologian) still mutes me on social media to this day.

I would be converted, though. First came Beyoncé, the 2013 surprise that dropped complete with music videos for each song. Lemonade and Homecoming strengthened my faith. And after Black Is King, I am now a firm believer that Bey is the MJ of our time. This is my testimony.

Sweet Beyhive, please don’t swarm down upon me. Forgive me when I confess that when Destiny’s Child dominated BET and the dance floors of my late twenties, I thought the Child to watch was LaTavia Roberson. When I first bumped into the most commercially successful girl group of all time, an editor had charged me with interviewing veejay-turned-talk-show-host Ananda Lewis over at MTV. She’d just wrapped up a segment with Destiny’s Child, and introduced me to the four members. I was far more excited to meet Ananda; I barely gave 18-year-old Beyoncé Giselle Knowles a glance.

Truth was, Destiny’s Child didn’t really speak to me. And upon the group’s disbandment, solo Beyoncé didn’t speak to me either. As a cishet male, I never felt her body of work took me into consideration. I don’t mean that I thought that was her responsibility. But the subject of “Bills, Bills, Bills” was a trifling, good-for-nothing scrub. The dudes addressed on “Bootylicious” weren’t ready for the jelly. Per “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It),” if we liked her then we should’ve proposed marriage. “Irreplaceable” said she could replace me in a minute, and in fact, he was on his way over. Dancing to her hits on dates or at parties felt obligatory, even embarrassing — and I’m sure a lot of straight men can relate. Loving Beyoncé meant embracing a level of masochism I wasn’t built for.

All the amazing music hung together as more than a collection of singles, more cohesive than everything she’d done before. When I wasn’t looking, Beyoncé became the center around which the pop universe revolved.

Yes, Janet Jackson asked “What Have You Done for Me Lately.” Madonna’s feminist anthems, like “Express Yourself,” weren’t written with me in mind either. But their music, personas, and presentations still convinced me to press play over and over on classic albums like The Velvet Rope and Ray of Light. Despite its obviously empowering overtones, something about Beyoncé’s music always felt like a middle finger, a great big “boy, bye.” I can remember when her solo career seemed questionable; her success wasn’t a fait accompli, believe it or not. Her very first single — “Work It Out,” from the Austin Powers in Goldmember soundtrack — didn’t even crack the Billboard Hot 100, though her hula-hooping in the video was hella hypnotic.

And yet here we be. Rolling Stone ranks “Crazy in Love” higher on its 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list (#118) than anything by either Janet or Madonna. In 2020, Beyoncé is pop music’s gold standard, and I for one now worship at the hem of her rainbow Thierry Mugler minidress.

I can’t say I deliberately listened to Dangerously in Love, B’Day, I Am… Sasha Fierce, or 4 more than once. (I know. Heresy.) But Beyoncé baptized me. I surfborted the wave of her internet-breaking album the night it appeared out of nowhere, and by 5 a.m. had written — I swear — the first review of Beyoncé on the internets. Visual albums weren’t new to my generation. Weren’t Purple Rain and Under the Cherry Moon Prince’s visual albums? Certainly the Rhythm Nation 1814 short film qualifies, among others. Beyoncé, though! All the amazing music hung together as more than a collection of singles, more cohesive than everything she’d done before. When I wasn’t looking, Beyoncé became the center around which the pop universe revolved.

I love a good concept album inspired by real-life ish artists go through. I grew up on stuff like my parents’ What’s Going On, the Motown classic created out of the Vietnam War experience of Marvin Gaye’s brother. Lemonade marked the fissure and reconciliation of her marriage to Jay-Z, set to Daughters of the Dust-worthy visuals and more incredible music. Does it appeal to my arty snobbism that Beyoncé seemed to set the pop-hit formula aside to hunt down higher art in her visual albums era? Definitely, though it’s not lost on anybody that all her secured bags from HBO, Netflix, and Disney+ in the past four years mean she’s even richer without topping the singles charts.

Homecoming aesthetically built on what she started when she mentioned she liked her “Negro nose with Jackson 5 nostrils” on Lemonade’s “Formation.” Meaning, she doubled down on serving up triple-stage Blackity-Black culture to her audience, White fans be damned. As a Morehouse grad, I soaked in all the easily recognizable HBCU marching band drumline rat-a-tat-tat in the Coachella performance that Bey later flipped into her Netflix concert special. As a proud Alpha, I picked up all the fraternity choreography and Greek letter imagery that went into the bombastic show. Beyoncé spoke to me. One of the grandest displays of African Americana in music that the world’s ever seen, Homecoming earned a place in the Black Smithsonian from day one.

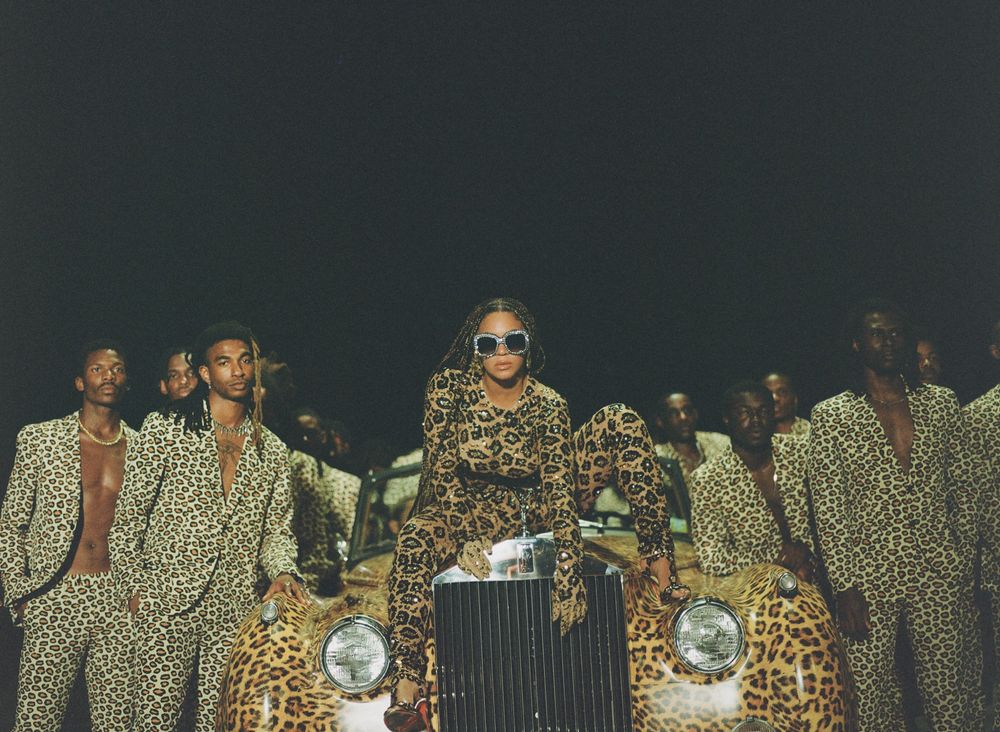

Her latest project, the pan-Africanist, Afrobeat-infused visual album Black Is King, has already stimulated deep-seated emotion (the empowering “Brown Skin Girl”) and a fair amount of critical thinking. Some have noted that Disney+ isn’t available on the African continent, questioning who this Wakandified version is really for. (Black Is King in fact streams in several African countries on the M-Net and Canal+ Afrique networks.) The images of hyperaffluent Africans — filmed in sections of Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa — serve a sweet spot in the Black American psyche that understandably loves to see our people dripping in prosperity, the way many of us prefer to imagine our ancestors and the precolonial motherland. Contrarians blasted Bey’s affirmation of capitalism and noted that none of her world tours have stopped through Africa. The fact that there are even two sides to the story of Black Is King proves that her art has transcended to another level.

“Y’all haters corny with that Illuminati mess,” Beyoncé dissed on Lemonade’s “Formation,” a response to actual accusations from conspiracy theorists about her membership in that theoretical secret order. A close friend had turned me onto the idea years before Bey addressed it, pointing out all the supposedly occult symbolism in her videos and explaining why he wouldn’t support her anymore. Seeing her at Citi Field in 2016 for the Formation World Tour, I laughed at the Jumbotrons during her performance of “Don’t Hurt Yourself.” Singing the line “Love God herself,” both screens the length of a baseball stadium flashed “GOD IS GOD. I AM NOT.” I expected no less from a humble Southern girl raised Christian down in Houston. Beyoncé is not a Five Percenter; she’s Beyoncé.

And yet. Midway through Black Is King, someone drops this voiceover: “I can’t say I believe in God and call myself a child of God and then not see myself as a god.” In an album of lyrics and Warsan Shire poetry full of ideas about royalty, manhood, and the beauty of Blackness, the quote can float by. But whoever it comes from, Beyoncé approved its inclusion, and the line recalls my favorite Bible verse. Psalm 82:6 reads, “Ye are gods and all of you are children of the Most High.” That said, Beytheism is long behind me. Yes, Beyoncé is God… aren’t we all?