On August 31, after 15 years, Patricia Waller was on the brink of being released from the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF). Instead of tasting freedom, though, she found herself heading hundreds of miles to a Colorado detention facility after California Governor Gavin Newsom handed her over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Waller was born in Belize — a country she has few remaining ties to but will soon be returning to against her will.

Being away from her family, community, and legal team has been “a little stressful, maybe,” Waller tells me over the phone one morning in mid-September, her voice shaking. “I’m trying to figure out where I’m going to go from here, starting over in a country I don’t even remember, with a felony record hanging over my head.”

Newsom’s decision to transfer Waller during a pandemic — something public health officials had advised against for months — has already resulted in Waller contracting Covid-19 inside the Colorado facility. But finally being released from quarantine early this week has been cold comfort for the 55-year-old woman, who could be deported to Belize as soon as this week.

Yet, across the country, dozens of people who have never met Waller have fought for her freedom from ICE custody, mailing her notes of support as they do. Waller considered these letters and postcards critical to remaining focused on her release and preserving a sense of faith beyond her immediate circumstances. “Mail is a big thing, you know,” she says. “When I receive letters, it puts a smile on my face. It reminds me that someone is thinking about me and I haven’t been forgotten.”

As a teenager, Waller became involved in a relationship with a man in San Diego who subjected her to verbal, physical, and sexual abuse spanning more than a decade. The experience “demoralized and degraded” her, Waller says, and she became a drug addict. At the age of 30, Waller made a series of poor decisions to fuel her addiction, which led to her incarceration. The charges made her, a lawful permanent resident, subject to deportation.

Waller is just one of many domestic abuse survivors across the United States who are incarcerated. The ACLU estimates that as many as 94% of some women’s prison populations are domestic abuse survivors — many for self-defense or other acts of survival. These survivors are often already marginalized — Black people, undocumented people, poor people, queer and trans people, sex workers, those who’ve already suffered at the hands of the carceral system, and beyond.

A number of high-profile cases in recent memory have demonstrated the insidiousness of that pipeline: Marissa Alexander, who defended her life from her abusive husband by firing one warning shot that caused no physical harm; Tracy McCarter, who is currently incarcerated at Rikers Island for an act of self-defense against her now late husband; and Nikki Addimando, who murdered her boyfriend in self-defense after years of physical and sexual abuse. The system is not structured to protect survivors.

“The question isn’t about the crime the survivor committed,” says Ny Nourn, an immigrant rights community advocate with the Advancing Justice Asian Law Caucus. “It’s about examining the larger system that perpetuates harm.”

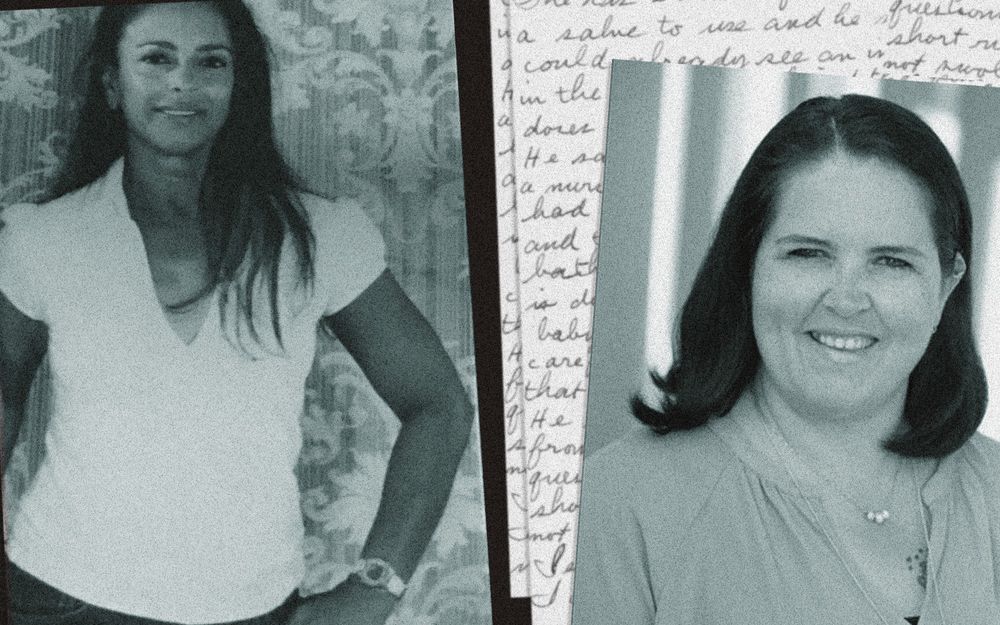

Every Tuesday, Waller speaks on the phone with one of her strongest advocates: Kelly Savage, a woman she met at CCWF. Since Savage’s parole in 2018, the women have remained connected via phone calls and letters; Savage has sent money to Waller’s commissary and helped facilitate communications with those on the outside. “She’s been by my side, even before all these issues with my deportation,” Waller says. “She accepted me for who I am.”

Savage, who was tried and incarcerated for calling the police after her husband murdered their son, understands how important it is for people to remain connected to the outside world. While incarcerated at CCWF, she’d sometimes receive upwards of 100 letters a month, some from people who would write to her weekly. “I once received an origami bird and hung it up on my bed,” Savage recalls. “It was something for me to look at, just to have some support when things got really difficult in court.”

Abolitionist organizations like Survived and Punished, SWOP Behind Bars, and Black and Pink identify pen pal relationships as a critical resource for those coping with the isolation of imprisonment. These organizations have coordinated thousands of pen pal relationships, connecting survivors like Waller with people they’ve never met, as part of their larger missions to fight for the fundamental human rights of incarcerated people.

Micah Herskind, who is working to launch Georgia Freedom Letters, another effort that works to connect incarcerated people with pen pals within the state, says that forging pen pal relationships was “a radicalizing experience” for him and was crucial in leading him to fight for the larger mission of abolition. “Prisons are incredibly isolating institutions by design,” Herskind says. “They erect physical walls between people and pose barriers to communication and access. With commitment, these pen pal relationships absolutely can turn into real friendships — real, solid, sustained relationships.”

Today, Savage, who initiated the first A Living Chance storytelling project, continues her work with survivors of both domestic violence and incarceration in various capacities, including a push to expand the Drop LWOP campaign, which has been fighting to end life without parole sentencing in California, to other states. Waller saw a similar path for herself, before Governor Newsom put her fate in ICE’s hands. “Kelly and I talk about this a lot,” she says. “I know the feeling, I know the fear, and all I want to be able to do is to help other incarcerated women that are going through this.”

While incarcerated, she’d sometimes receive upwards of 100 letters a month, some from people who would write to her weekly. “I once received an origami bird and hung it up on my bed,” Savage recalls. “It was something for me to look at, just to have some support when things got really difficult in court.”

A month after our initial conversation, I called Savage again to find out what Waller may be facing in Belize. The picture she painted was grim: Waller will have to search for her remaining family, whom she hasn’t seen in decades, from an unknown drop-off point. The country’s bank accounts that Savage has looked into cannot hold more than $1,000 at any given time. “We have people who we’re trying to help on a daily basis, and when they get deported, we lose all contact,” Savage says. “That, to me, is a travesty.” Organizers are now working to raise money for Waller’s re-entry fund so that her basic needs can be met in Belize, and they are gathering more letters of support. Down the road, Savage tells me, the challenge will become helping Waller find income and stable housing, as well as reestablishing sustained contact.

Activists have pushed for a number of measures to help individuals like Waller, ranging from legislative reform (such as allowing those who’ve been deported to reenter the United States) to continuing the fight to abolish prisons and ICE and end deportations outright. But for Savage, whose own 2015 habeas petition for a new hearing was opposed by California’s then–Attorney General Kamala Harris, the incoming administration doesn’t hold much cause for hope. “They care more about politics and getting themselves higher in the ranks than their position to support the community,” she says.

Herskind echoes the same concerns, stressing the importance of ramping up mutual aid and letter-writing efforts in the coming years as a response to the state’s negligence. Georgia Freedom Letters, for example, is currently working on helping incarcerated people in Georgia access information about their CARES stimulus eligibility. “When we support those inside, we are working to give them a pathway to rejoin our communities upon release,” Herskind says.

As dire as Waller’s situation is, it’s also tragically familiar: In 2019, ICE detained 143,000 people and deported 267,000. “Everybody’s really concerned,” Savage says of Waller’s impending deportation. “But all we can do is continue to push. There are so many factors to consider, and I’m going to try every avenue to support Patti.”

After all, Savage has done it before: She has one friend in Mexico and another in South Korea in similar circumstances as Patti Waller, and she has managed to stay connected and support both of them. But she can’t do it alone. “It’s going to take much more than just one or two organizations being able to fight for something so important,” Savage says. “It takes a community.”