Conducting hours of on-camera interviews can be taxing—just ask any documentarian ever. Yet sifting through seemingly endless footage to produce a passion project can feel like the most rewarding kind of treasure hunt.

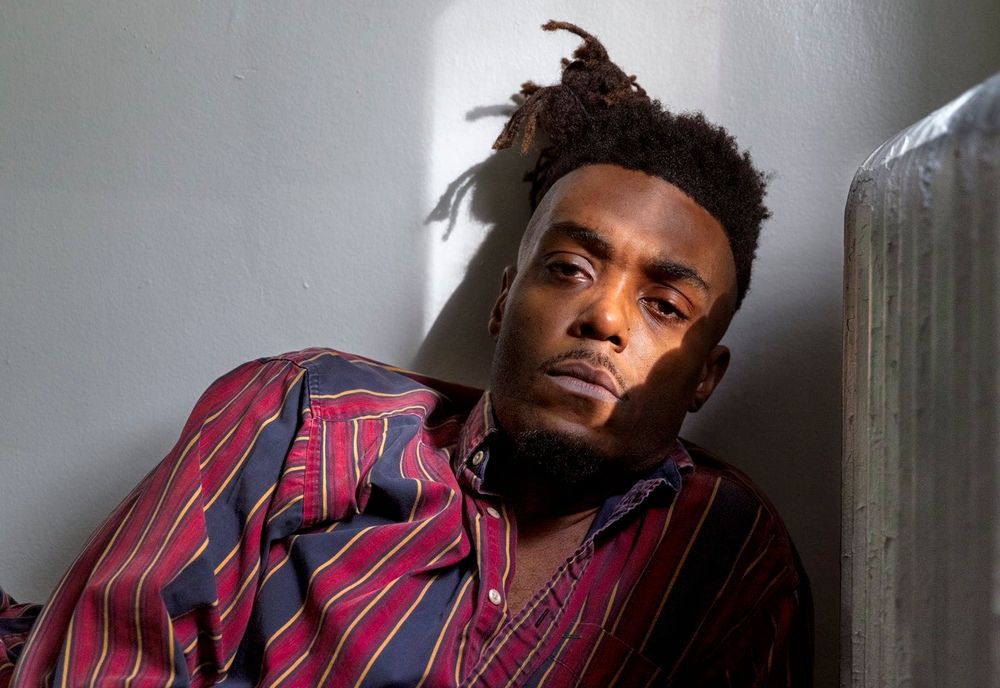

Self-tasked with telling the stories of 100 LGBTQ couples, 32-year-old journalist and author Jamal Jordan has developed a visceral method for deciding which clips to include in Old & Queer, a video series that puts the spotlight on older queer couples. “I really love the feeling of being devastated by a single line,” he tells LEVEL. “I just wait for the sentence that hits me. Usually, it’ll hit someone else, too.”

Playing back a recent conversation with a trans woman, that collision arrived in the form of casual serenity. In her recollection, the woman, then 17, was wearing women’s clothing for the first time when a crush told her she was pretty. “You get to the moment where she has this smile—the first moment where she's like, ‘Oh, I'm a pretty girl!’ and I'm like, ‘Oh yeah, that's it.’”

These videos are Jordan’s way of giving power to those who’ve been told their stories aren’t worth sharing. The former New York Times staffer documented those neglected experiences in Queer Love in Color, a photographic book published last year that explores the intersection of queer and POC identities with rare intimacy.

Old & Queer, which he began unveiling earlier this year, is an offshoot of the same goal. His plans to speak with queer seniors stemmed in part from his own inability to imagine himself as an old lover. While working on Queer Love in Color, he encountered two elderly Black men engaged in a loving relationship, and the possibility began to sink in. Now, through his new series, there’s a chance he can help others have the same representation.

“I think being able to fill in that history for queer people has been really grounding to understand that you're not unique in the things that you're experiencing,” Jordan says. “But you're also not alone in them either.”

Jamal Jordan dialed up LEVEL to discuss his experience working on Old & Queer and share the treasures he’s unearthed in the process.

LEVEL: What made you want to embark on Old & Queer after publishing Queer Love in Color?

Jamal Jordan: Two things happened. [While] making this book, I was working at The New York Times. I hated my job. I was on book leave and I was like, Oh, I should try to do some cool stuff to elevate myself at work. So I pitched this elaborate story on queer aging. It had been on my mind that I hadn't spoken to many queer elders. No one tells their definitive story. Then I dislocated my shoulder and that makes photography really hard [laughs] so I just did an abbreviated version of the story. But the seed had been planted.

While I was making the book, I was meeting these older couples and I realized I had no conception of what that aging was like for me. There was one couple in particular from my book named Mike and Phil, I excerpted their story for The Washington Post. They talked about how little they see older gay men foster relationships with younger queer people.

Phil had this father-like tone. He was like, “You know, I wanna write a book and I want you to go write a book yourself and tell these stories.” I was like, “Okay, damn Phil!” Having an 80-year-old Black man tell you something, go do it. When the book was finished, I was teaching my class at Stanford. One of my students gave me this speech about how she had never had any older person to talk to. I'm 32—she was like, “Yeah, you're kind of like the elder right now here for me.” That combination of things all came together to become the project this is now.

When you began Old & Queer, what did you expect to find ?

I was expecting a lot of trauma and people being like, “Life was so much harder for me than it is for you. I'm so envious of the progress that you got and the freedom you guys live.” Part of what shifted is I'm learning the power of community and how much freedom people were able to find, even in times that were oppressive. I had one couple like, “We're having a great life. You should look forward to this.” I loved hearing about the community structures of queerness that existed in the ’60s and ’70s.

I came into it [thinking] older queer people are more homeless, poor, have experienced discrimination in housing, healthcare, live less fulfilling lives, have fewer friends. And they're like, “No, some of us had it pretty well.”

All these people say they have multiple physical spaces where they could go meet and talk to people. They were less reliant on social media, which meant they made more genuine connections. Everything wasn't always so bad and everything isn't perfect now. And there are in fact lessons about being happy that we can learn from that time versus pity that should be bestowed upon them because of the difficulty they had. I came into it [thinking] older queer people are more homeless, poor, have experienced discrimination in housing, healthcare, live less fulfilling lives, have fewer friends. And they're like, “No, some of us had it pretty well. You should aspire to some of the things we did, too.”

Where were some of these spaces where they could meet up?

Post-1980s, most cities in the United States became much more corporatized. So, in general, it is harder for any subculture to have physical space. Things that would be art galleries, nightclubs, or cafes, just don't exist. With that larger American context, I feel like that specifically hampered the LGBT community, whereas in the 1960s and 1970s, everyone spoke of having a bookshop, a bath house, a club, a bar, a restaurant they all could go to. In California, there were multiple lesbian bars that were signified by the no-military allowed signs outside.

All throughout the country there were examples of this. A lot of queer people that age just understood community building had to be intentional; they had no [other] choice. Obviously, the ease of meeting queer people online is awesome. But there's less that bonds us as a community because we're fighting for fewer things together. I think there's less intentionality between building community spaces.

I would think older members of the queer community aren’t as active on social media and younger people. How did you contact them for this project?

I'm very much a reporter in that when I have something I want to find, I become obsessed. I usually will call every LGBT-associated organization in a [city]. Boomers love Facebook [laughs]. A lot of times I’d meet one doctor or counselor who's like, “Find this person on Facebook and I'll send a message.” Eventually, they'll be my entryway into the community. Queer people tend to have strong community ties with each other. Finding your way in and being a trusted person in that community then opens doors to meet other people.

I can find people in a day. The harder part is helping [less Internet-savvy] people understand how their story will exist in the media. Every apprehensive person I've had, once I start talking to them about their lived experiences, we get to the point where we’re like, “In 1950 and 1960, all you wanted was to see someone like you exist in the world.” And you understand that now no matter what age you are.

Those kinds of conversations can be cathartic. Did you ever find that the people you interviewed had new realizations about themselves?

I was in Palm Springs and I met a woman named Candice Nichols. She's an executive of [an LGBT] organization. She worked as an AIDS companion for dying people in the ’80s and ’90s. I asked her what that was like and I remember she said, “I haven't actually had to talk to a young person about what it's like seeing someone their age die.” She's like, “It's weird being here with you because when I was your age, I was watching people your age dying in front of me the whole time.”

She does a lot of work to help older people and younger people have these intergenerational conversations and she says, “I always encourage older people to tell these stories because we think about them, but we don't talk about them very much. And telling these stories changes not only the person who hears them, but [also] the person who tells them, because you get these chances to make odd connections between what you thought was in the past and what's happening in the future in front of you.”

What's your favorite part about working on all of these projects?

Finishing them. No, I'm kidding [laughs]. I do love doing longitudinal journalism projects that take you to a lot of different places. I dislocated my shoulder while working on my first book in Jackson, Miss. [My] closest family member was like a two-hour drive away. I emailed all the people I was supposed to meet like, “Hey, I'm in the hospital, I can't meet you.” And all these strangers were just taking care of me [laughs]. Someone picked me up from the hospital. Someone made me food. I went to interview someone and they laid out this entire spread of snacks and wines for me.

So many people are so eager to share their stories. I felt like part of a very large community of queer people. These people invited me to their homes and to meet their families and their friends. Everyone was so open. There's something about understanding the community that comes from queer people, sharing stories with each other that has made me feel really grounded and happy. But also, finishing is my favorite part, too. Because there’s nothing better than having work be out in the world and seeing what things people connected that I may have missed. I love all that shit. Storytelling is the action of connecting other human beings.