On “Represent,” the ninth track on Nas’ 30-year-old classic album, Illmatic, the Queensbridge prodigy notes a striking parallel: “Somehow the rap game reminds me of the crack game,” he rhymes. And yet, for all of that symmetry, one could find a similar correlation between the music industry and American politics.

“They both specialize in using people,” says Jesse Washington, writer and director of a new documentary titled Hip-Hop and the White House. “You know how [record labels] do: We love you today, you're the best thing. But let you cool off for a little bit and you will get kicked to the curb in a second. That happens in politics, too.”

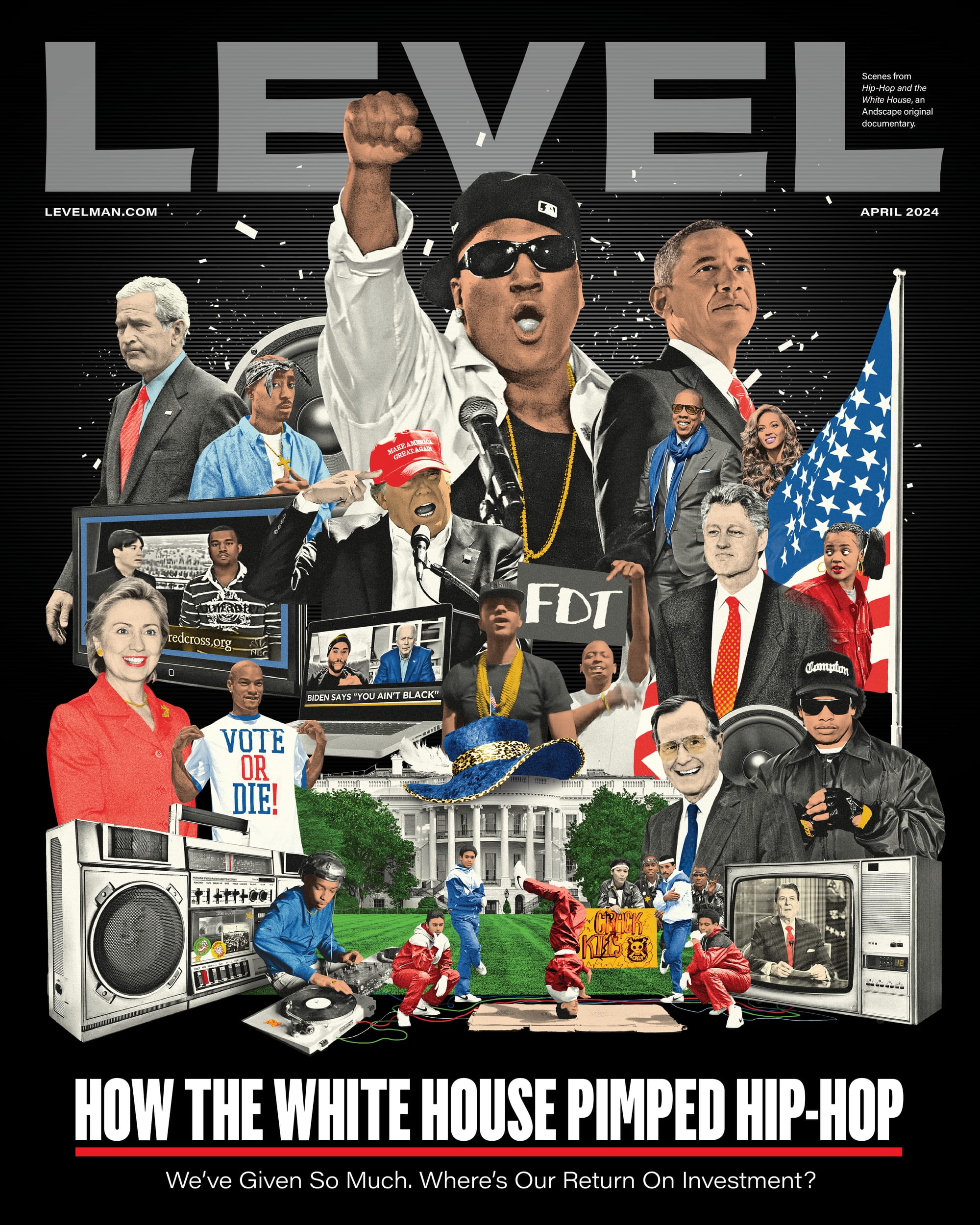

Presidential surname aside, the author and veteran journalist is especially primed to make this observation. He dove into these forever intertwined entities while crafting the aforementioned doc, which chronicles the many ways the culture has imprinted on the Oval Office, and vice versa. It’s all there: from Nixon to Biden, Vote or Die to FDT, “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” to “You ain’t Black!” Jeezy serves as the film’s executive producer, joining Common, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters, KRS-One, YG, Chika, Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, and Waka Flocka Flame in sharing commentary. (You’re gonna want to tune in to hear the latter’s viewpoints.)

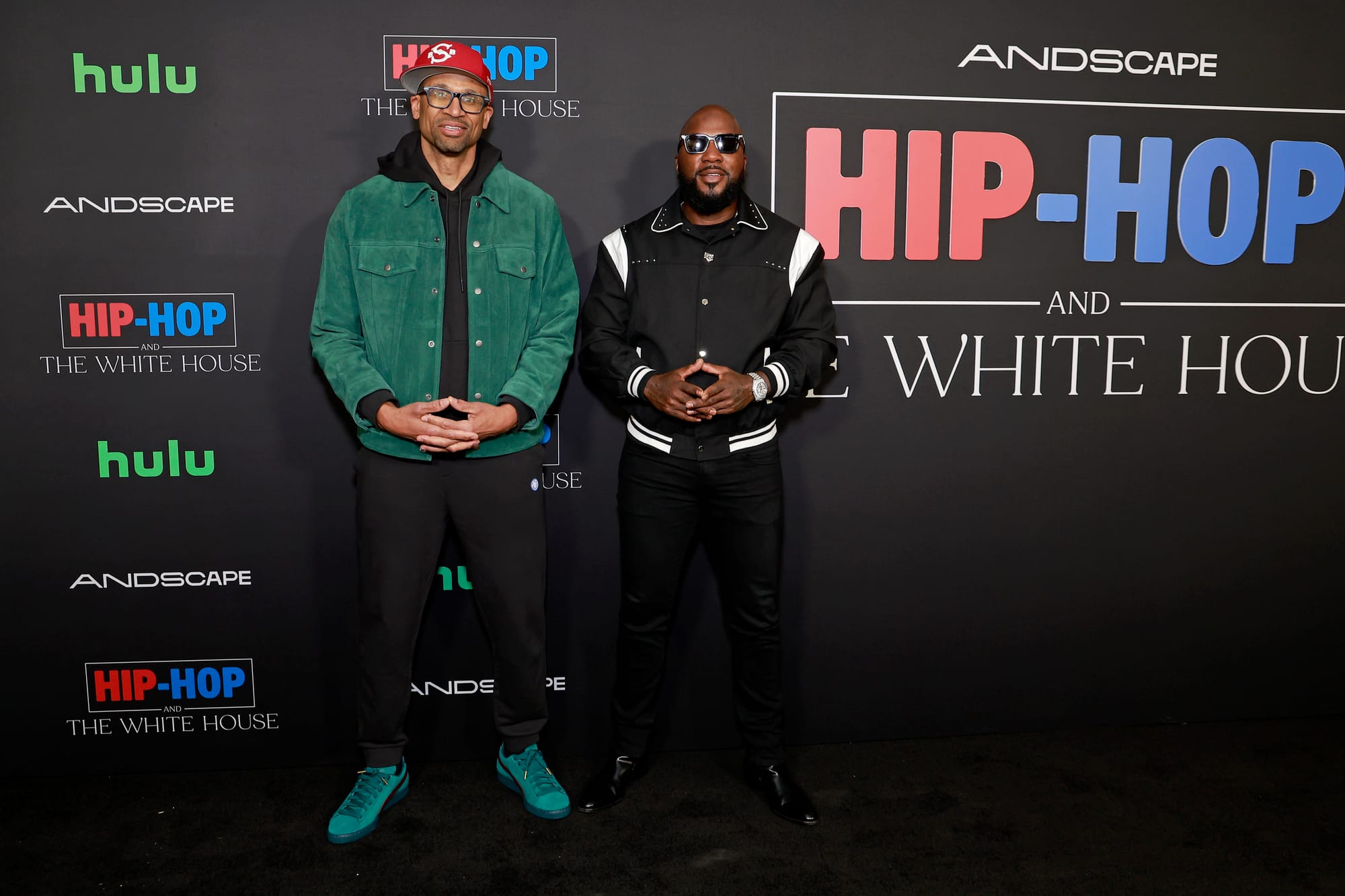

The premise of Hip-Hop and the White House began as a series of video shorts intended to live on YouTube. But the subject matter proved to be too vast, too fertile—especially with a pivotal presidential election on the horizon. It’s now presented as an hour-long documentary (out today via Hulu), the first offering from Andscape’s anthology series, &360. It’s Washington’s first full-length film, just the latest accomplishment in a storied career that dates back to hip-hop journalism’s golden age of the ’90s (stints at The Source, Vibe, and Blaze) and includes memoirs for sports agent Rich Paul and late Georgetown coaching legend John Thompson.

Related: How a Few Great Hip-Hop Journalists Won in Hollywood

Days before the Hip-Hop and the White House debut, LEVEL hopped on the horn with Washington to chop it up about his new film, why the most impactful political songs come from unlikeliest of sources, the Kanye West conundrum, and how hip-hop can elect our next president.

LEVEL: Jeezy is an executive producer of Hip-Hop and the White House, and he also narrates and appears in the film. Why was it important to have him involved?

Jesse Washington: There's no way we could have done this doc without his full participation. Jeezy has one of the biggest political songs of any genre ever. Go down the history of songs about presidents and presidential administrations; his is at the top of the list. It's wild. Going into it, I didn't know he recorded [“My President”] months before [President] Obama was elected. This man saw the future. Based on the stature of that song alone, he had to be in it. Fortunately, he agreed to participate with us.

“Eazy-E was the first rapper to be in the same room and have an encounter with a U.S. president. I remember when that happened—it was a big moment.”

One thing I realized while making this film is many of our biggest political hip-hop songs did not come from political artists. A lot of the giants in hip-hop have such an organic and inseparable relationship to the people, the streets, and the essence of Black America that they are able to speak for and to them in the most powerful ways. Jeezy fits that bill and is very emblematic of that.

I never thought of it that way.

It really starts with [N.W.A’s] “F*ck the Police.” That was a supremely political record. In the film, Bakari Kitwana, one of our journalist colleagues, says hip-hop is always political because of the context in which it was created. We really went out of our way to document what presidents were doing to our communities when hip-hop was born, how young Black people have been targeted and politicized by our treatment from the highest office in the land: Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan. Once we set that context, you understand how their policies impacted hip-hop. Then Eazy-E makes perfect sense. Jeezy makes perfect sense. YG makes perfect sense. The bookends to this film are really Eazy-E and YG.

This is not to take anything away from the brilliant politically oriented artists—Chuck D and Public Enemy being at the top of that list. They absolutely have moved the needle in humongous ways. But the music industry—not being controlled by us—pushed that type of music to the background in the ’90s and elevated other genres. But they were not able to snuff out a political consciousness that just came from an unexpected source like YG. He's amazing in the film, by the way, because he's so authentic [and] honest.

The film covers Eazy-E’s 1991 meeting with the Republican Senatorial Inner Circle, under President Bush’s regime, as a landmark moment in this history. What was its significance?

Eazy was the first rapper to be in the same room and have an encounter with a U.S. president. I remember when that happened—it was a big moment. Mostly people were like, “Yo, what is he doing? Why are you there, bro?” In [“No Vaseline”], Ice Cube said, “I’ll never have dinner with the president.” He's taking shots at Eazy for going there. So it was such a huge moment, and for it to be Eazy-E is wild. Rappers had been making songs about presidents and candidates before that, but this was the person who got in there. I think that's very meaningful.

“When Kanye said [‘George Bush doesn’t care about Black people’], it was a moment that will last forever. Nothing Kanye can do now, in my opinion, can ever erase that contribution. He held the president accountable in a way that only hip-hop could.”

I saw a throughline from Eazy-E to Kanye West, whose history includes calling out President G.W. Bush on live TV, a tense relationship with President Obama, and becoming Donald Trump’s most visible hip-hop supporter.

I'm glad you brought that up. Kanye was a lot [Laughs]. But you have to give him credit. [Hurricane] Katrina was this huge moment in Black American history because of what happened to us through the neglect of the federal government. And when Kanye said [“George Bush doesn’t care about Black people”], it was a moment that will last forever. Nothing that Kanye can do now, in my opinion, can ever erase that contribution that he made. He held the president accountable in a way that only hip-hop could do. It was a bar.

The transformation of him going over to Trump is really important because, if we're really being honest, 2020 exit polls showed that about 20 percent of Black men voted for Trump. And who likes Trump? Rich people, celebrities, men with a certain negative attitude about women. There's a lot of overlap there with hip-hop. Are we really surprised that Kanye is down with Trump like that? After putting the film together, I was like, “Oh, this makes perfect sense.” He's the type of dude who would rock with him. There's always been this dance that hip-hop has done with Republican presidents. We're still doing it—shoot, we breakdancing now. We’re on the floor spinning with them jokers.

The timing and scope of this documentary beg the question: What impact will hip-hop have on this year’s upcoming presidential election. What’s your take?

We're in an interesting moment politically in this country. We're in uncharted waters—and not only in terms of the types of candidates on the ballot for president this fall, but also the position of Black voters. That's why this documentary is so timely. Hip-hop has more influence than it has ever had before in a presidential sense, because our reach is multi-generational. All of these artists can speak to hip-hop in a very powerful way when it comes to this election. So what are we going to say and do?

One of the great things about this project was that I learned so much—I got to interview almost 20 people with different perspectives, experience, and wisdom. Congresswoman Maxine Waters said hip-hop has not realized its full influence yet, so we have the potential to do so much more. Bakari Kitwana gave a very specific suggestion: properly organize. If hip-hop wants to have a full influence—not just on who's elected, but what hip-hop culture and our communities can get in exchange for our support—then we need to partner with individuals and organizations who are experienced in these spaces. That is how you actually get things done.

The rap game works the same way. If anybody knows about how to get to the plug and influence things, it’s hip-hop. In a way, we're really built for it. So we have to strategize and have a plan. Not only could hip-hop play a role in the election; hip-hop could play a role in what comes after, no matter who gets into office.

Would you say that hip-hop and presidential politics have a mutually beneficial relationship, or are the scales leaning in one way?

Let's be clear to distinguish between hip-hop and the rap industry. Two different things, but they overlap. For better or worse, the rap industry tends to overshadow everything else about the culture of hip-hop. That said, the rap game and politics are very similar. They both specialize in using people. Anybody who’s spent a couple minutes dealing with any type of record labels—come on, man. You know how they do: We love you today, you're the best thing. But let you cool off for a little bit and you will get kicked to the curb in a second. That happens in politics, too. So I think rap and [politics] have been using each other. They're made for each other.

We definitely raised that question throughout the film, even with Obama, who was down with hip-hop and I believe has a true love for the culture. He's still a really smart politician. And at the end of the day, that's how they operate. No shade to Obama; thanks, good looking [out]. But let's call it what it is. So I think hip-hop and presidential politics will continue to have this interesting relationship, much of which revolves around using the influence of the other party to benefit our own goals, whether that's helping the community or selling records.

"If hip-hop wants to have a full influence, we need to partner with individuals and organizations who are experienced in these spaces... If anybody knows about how to get to the plug and influence things, it’s hip-hop."

Ice Cube falls into that description of someone trying to work with the political establishment to get an agenda realized, even if the optics of his dealings with Trump were polarizing.

Ice Cube is a very interesting situation, because that’s somebody who has been perceived to have moved from one side to another, which I don't think is totally fair. Cube was being pragmatic—being like Jim Brown in terms of, Okay, how can I get things for my people? Whoever is in power, that's who I'm going to rock with. And I'll tell you what, neither Ice Cube nor Jim Brown is anybody's house negro. They just have a different way of doing things. That would've been really cool to get into [more thoroughly in the film].

This is your first full-length documentary, and you covered a robust topic. Did you run up against any limitations in how deeply you could capture it?

Oh, yeah. All kinds of stuff. It's hard to put music in documentaries because it's expensive. [Lil] Wayne had a song called “Georgia… Bush” after [Hurricane] Katrina, and he’s rapping over Ray Charles. Our music people were like, “This song is unclearable.” [Laughs] I would've loved to put that in there. I would've loved to go down the Kanye-[Donald] Trump rabbithole and really deconstruct that whole situation. There's a lot more moments as far as hip-hop getting at presidents that I would've liked to explore. But you only got so much time. You only got so much money.

Switching gears: Much congrats for co-writing Rich Paul’s book, Lucky Me: A Memoir of Changing the Odds, which is a bestseller. What did you learn through that process?

I learned a lot about who Rich Paul really is. I knew the public image and the narrative around Rich—a lot of people resent him for his success because they falsely perceive that he did not earn it, that it was given to him. So the title of his book, Lucky Me, is deliberately ironic. I learned that Rich is an extraordinarily gifted individual; his gifts come from an incredibly difficult and dysfunctional upbringing... Those of us who come up this way can use that to develop ourselves into something special. It's something that more privileged people can never get.

There's a whole other side of Rich Paul that nobody really knew about and that he chose to describe for the first time publicly in this book. These guys don't just sit down and tell you everything off the rip. It's a process. In both of the books that I've written, the author had to work through these issues for themselves as they're telling their story. These are deep, traumatic, difficult, challenging situations that they went through. Sometimes they just put it away in order to survive. But with Rich, I sort of went on this journey with him as he delved back into his very difficult past that nobody in the public ever knew. It was really special to be able to help him share that story.

As a writer, how do you go about establishing that rapport and getting someone to trust you enough to open up and be vulnerable?

You have to earn it. And you earn it through being genuinely there for them to tell their story in their voice, to figure out what they want to communicate, and to help them overcome the barriers to fully revealing themselves. The No. 1 thing is you got to be genuine. Writing a book for Rich Paul or I Came As a Shadow for the late great Coach John Thompson, from Georgetown, I consider it an act of service. I'm not here to do my thing; I'm here to do your thing. Then they have to see it on the page that this is [their] voice and feelings and soul. Then there's the other part: You have to understand how much they want to reveal. Nobody's going to reveal everything about themselves. Everybody deserves to keep some things private. I have to show them I understand what it is that you don't want to reveal.

Coach Thompson and I had a joke where I would say, “What's not in the book is going to be better than what's in the book.” He’d say, “Yeah, and they'll never read that one.” After a while, he would tell me something and I would say, “Yeah, that sounds like it's for that other book, Coach.” He'd say, “Yeah, that's right.” But if they don't tell you everything, then you can't get the full picture and understand what not to say. You have to show them that you're genuinely there to tell their story, and then you have to do the work, man, and put it on the page in a way that they appreciate and respect and feel represents who they are.