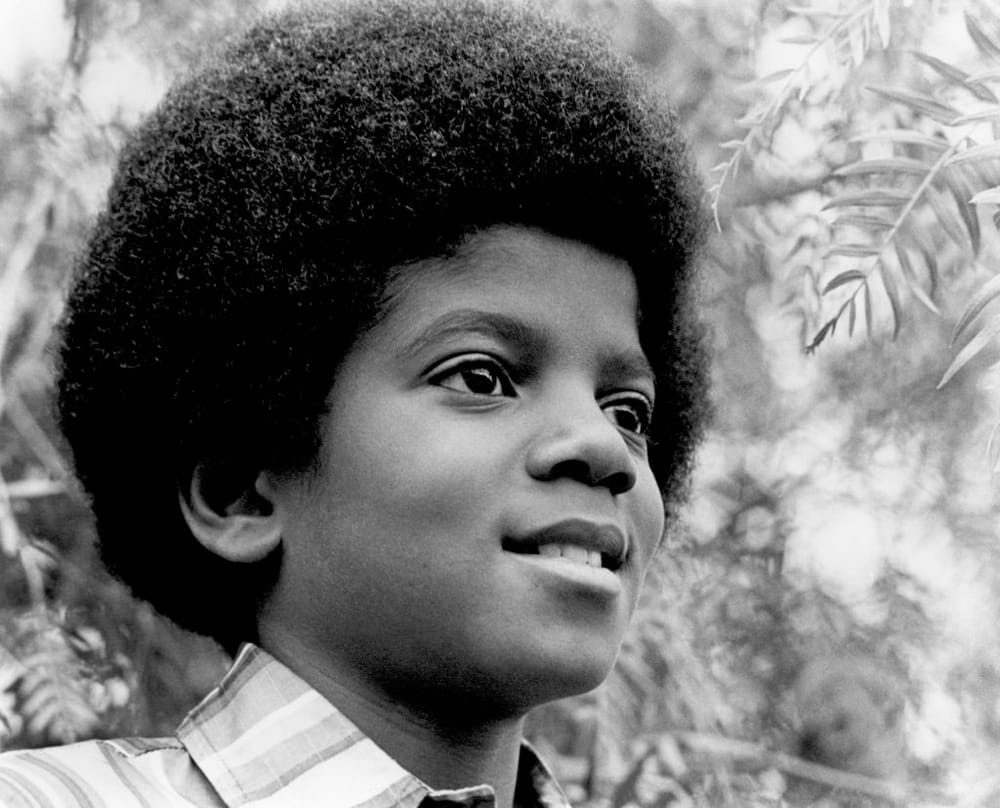

It’s a seemingly throwaway line from what is now remembered as the most successful single in the catalog of the Jackson 5, and one of the best-selling singles ever for Motown Records. “I’ll Be There,” recorded in June of 1970, became the fourth (and last), in what was an unprecedented debut run of number-one singles for the foundational “boy band” of the late 1960s and early 1970s. As the song edges to its closing and the young lead Master Michael Jackson repeats the lyrics “I’ll Be There,” he offers this addendum “just look over your shoulder, honey.” That this eleven-year-old could seamlessly improvise in that moment is notable in and of self, but the ad-lib, was a citation of an earlier ad-lib (minus the “Honey”, which was all Master Jackson), uttered by a grown-ass man, Levi Stubbs as he transitioned into the final chorus of the Four Tops’ hit, “Reach Out (I’ll Be There” (1966).

Though recorded only four years apart, Jackson’s ad-lib offered a bridge between a particular moment in Black music history where male and female groups in matching suits and dresses and dressed the part of “credit to our race,” and the future of that Michael Jackson, who became a global superstar. The performance was also early evidence of Jackson as a repository for the past, present and future of Black music, whether articulated as an obscure ad-lib or his channeling of Earl ‘Snake Hips’ Tucker, a popular Black dancer in the 1930s, with his signature “Moonwalk”.

When Michael Jackson reached the commercial apex of his career in the mid-1980s, he did so not only on the strength of his formidable talent and creative vision, but also as the most visible embodiment of the broad traditions of African American and Diasporic musicality. Throughout his development Jackson functioned as an archival resource of Black movement, voice, and gender performance, which he deftly managed and negotiated in performances that were as flawless as they were fluid.

It is useful here to read Margo Jefferson from her book, On Michael Jackson, where she describes Jackson’s stage performance as a “hoofer,” “Soul Man,” and “Song and Dance Man,” elements of what Jefferson calls “musical theater melodrama,” “chitlin’ circuit bravado” and “Motown mime.” Jefferson could have just as easily inserted the names of Fred Astaire, James Brown, Gene Kelly, Sammy Davis, Jr., Diana Ross and Stephanie Mills and her point would have been made just the same. Jefferson highlights the extent that Michael Jackson’s performance, though steeped in tradition, regularly enacted a form of simultaneous recognition and erasure — the latter act brought about by the nature of Jackson’s virtuosity.

Jackson’s inspirational archive was wide-ranging. The Chitlin’ Circuit, the network of Black clubs, speakeasies and theaters that catered to Black audiences during segregation, were in the spirit of Jackson’s interests in P. T. “The Greatest Show on Earth” Barnum, Jackson’s own musical and performance circus. The Chitlin’ Circuit allowed Jackson to develop his signature performance gesture; that of rendering his primary influences as obscure, while making his own performance of those influences ubiquitous. This move by Jackson is as much about his artistic ego — his literal interest in being the “Greatest Show on Earth” — as it was about his respect for cultural and racial communities that cultivated his talents.

There is an old, tiresome debate regarding the debt that Michael Jackson owed to Elvis Presley– the so-called “King” of Rock ‘n Roll. It is a debate that usually diminishes the profound impact that earlier generations of Blues and Rhythm and Blues artists had on Presley. Jackson sheds light on that debate in his memoir Moonwalk, where he casually dismisses Presley’s influence — a tactical choice no doubt, regardless of whether truthful — choosing instead to highlight the influence of Chitlin’ Circuit artists such as James Brown, Jackie Wilson and Joe Tex.

Jackson recalls that as a child he was “like a sponge, watching everyone and trying to learn everything I could.” On the Chitlin Circuit, Jackson could, as he describes in Moonwalk, study “James Brown, from the wings,” knowing “every step, every spin and turn.” Of Jackie Wilson, Jackson writes that he “learned more from watching [him] than from anyone or anything else.” Again, perhaps this is a tactical choice by Jackson, paying deference to Wilson five years after the singer’s death, though there is actual archival footage of Jackson’s Motown audition that looks like a “how to dance like James Brown” video.

Jackson’s cover of Smokey Robinson’s “Who’s Lovin’ You?” is just the first example of a long tradition Jackson sampling from the archive. Recorded in the Spring of 1969, Jackson’s “Who’s Lovin’ You?” drew attention because he conveys a sense of carnal knowledge seemingly well beyond his years. This sense of sexual knowing, evident in Jackson’s early recordings, as witnessed in the now famous “Shake it baby” break-down from “ABC,” was the by-product of the Jackson 5’s days performing at strip clubs. Jackson is less convincing, covering Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine” on his solo debut Got to Be There (1971) Yet, Jackson’s version is an example of the rhythmic quality of his vocal instrument, another early example of the way that rhythm, movement and voice are seamlessly embodied in Jackson’s performance.

Jackson’s vocal authority — his willful desire to obscure — is not yet fully realized; accordingly, a bevy of “wanna be” Michael Jackson vocalists cropped up immediately with the success of the Jackson 5. While the Osmond’s “One Bad Apple” produced by Muscle Shoals veteran Rick Hall was more an attempt to capture the “Jackson 5 in a bottle,” in comparison New Birth lead singer Londee Loree was a dead ringer for a young Michael Jackson on tracks like the band’s cover of “Never Can Say Goodbye” or most famously “It’s Impossible.” The New Birth tracks were notably produced by Motown veteran staffer Harvey Fuqua.

We began to see Michael Jackson’s vocal authority emerge with the signature grunts, slurs, gasps and “schumas” that become part of the repertoire as a teen and adult, leading the late artist Faith Ringgold to suggest to her daughter, cultural critic Michele Wallace that Jackson “makes up words.” Jackson’s vocal expressions were likely a broader attempt, one that might have been unconscious, to sync his sense of rhythm with movement and vocal expression. This percussive aspect of Jackson’s vocals is enhanced throughout his career and can be framed by his performances on “Wanna Be Startin’ Something,” and “Remember the Time.”

The closing segment of “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin” is heavily indebted to the music of late Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango and his song “Soul Makoussa.” While Jackson’s debt to African pop was fairly well-known among older Soul and Disco fans — “Soul Makossa” was a big club hit in the US in the mid-1970s — Jackson refigures those rhythms in his vocal runs on “Remember the Time,” a song and John Singleton directed video that brilliantly trades on the desire among young African Americans at the time for “Afrocentric” nostalgia.

Towards the end of his life, Jackson seemed to distance himself from being phenotypically Black, whether by choice or his claim that he suffered from Vitiligo. Yet the irony is that Jackson’s music and performances remained in deep conversation with the traditions of Black music. Jackson always remembered his early days on the Chitlin Circuit and the lessons that it taught him.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.