Nearly 35 years before the release of Lady Gaga’s Born This Way, a Gospel singer turned Disco star, recorded a song bearing the same title, which became one of the era’s most important Queer anthems. That a Baltimore bred, African American man, who came of age during the height of Civil Rights movement could so seamlessly wed the Gospel impulses of this nation’s most affecting social movement, with the nascent impulses of the LGBTQ movement — “Yes, I’m gay/tain’t a fault ’tis a fact/I was born this way” — should not be surprising. That Bean did so while recording for Motown Records, a company that symbolized the push for Black integration and respectability in the 1960s and 1970s, should elicit some wonder.

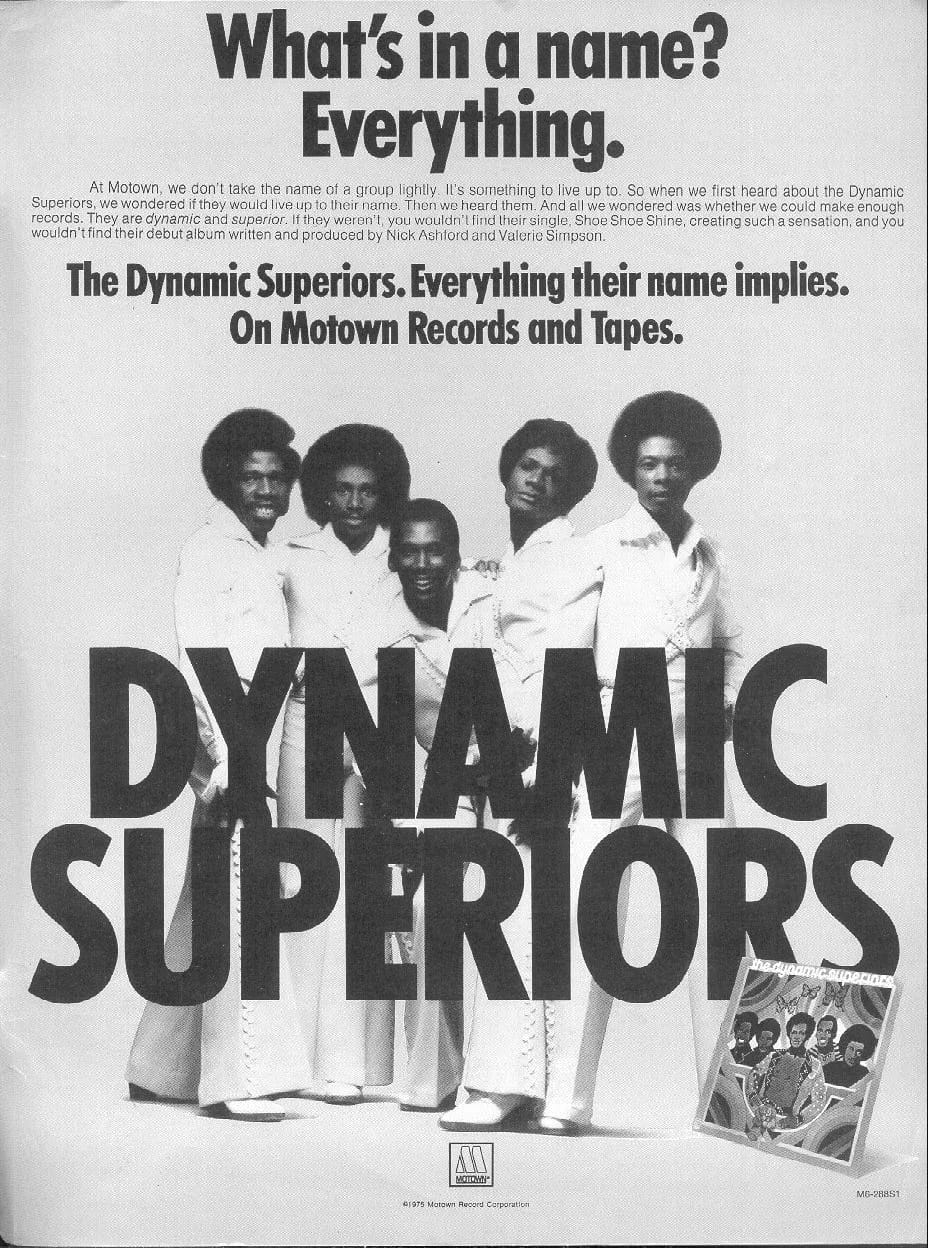

Bean was not alone; in the mid-1970s the Motown roster also included the vocal group the Dynamic Superiors, whose lead singer, the late Tony Washington, was an out and flamboyant Gay man. Though the musical legacies of both acts, have been largely obscured over the years, their connection to, arguably, the most prominent Black brand of the 20th Century speaks volumes about how inclusive Berry Gordy’s vision was with regards to what he called the “Sound of Young America.”

Whenever the subject of Black music and Queer identity is broached, the figure of Sylvester, the groundbreaking Disco and Dance artist, is immediately recalled. While the Dynamic Superiors and Carl Bean where contemporaries of Sylvester, it is important to remember that both acts had already broken through to the mainstream before Sylvester released his influential classic Step II in 1978. As a solo artist committed to drag performances, Sylvester became the quintessential example of Black artists who successfully challenged the boundaries of race, sexuality and gender. Sylvester was indeed peerless, but not without precedent, if you consider artists such as Billy Strayhorn (Duke Ellington’s longtime contributor), Nona Hendryx, and Bessie Smith, to name just a few.

Not surprisingly, even Sylvester owed some debt to Motown for his success. Sylvester’s 1977 solo debut Over and Over was produced by Harvey Fuqua, founding member of the doo-wop group the Moonglows and one-time Motown record executive, who was responsible for bringing Marvin Gaye to the label. The title track of Sylvester’s solo debut was a cover of a Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson song, featured on their 1977 album So So Satisfied. Ashford and Simpson, of course, were the well-known song-writing duo behind the great Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell recordings of the late 1960s; they were also responsible for the songwriting and production on the first two Dynamic Superior recordings, their eponymous 1974 debut and Pure Pleasure (1975).

Products of the Washington DC housing projects, the Dynamic Superiors began singing with each other as high school students in the late 1960s. Their big break came when they performed at a music industry showcase in 1972 and were spotted by Motown executive, Ewart Abner, most well-known for his work as President of Black owned Vee Jay Records. Abner helped guide the careers of Gene Chandler and Jerry Butler, and Vee Jay distributed the initial American releases from The Beatles. The group was quickly signed by Motown and their first album The Dynamic Superiors was released in 1974. The lead single, “Shoe, Shoe Shine,” was in the vein of the popular harmony groups of the day like the Stylistics and Blue Magic, and as lead singer, Tony Washington’s falsetto was every bit the match of Russell Thompkins, Jr. and Ted Mills, respectively.

Yet, Washington exuded something more — a something more that can be easily recognized on the cover art from that first album. For a label that years earlier released an Isley Brothers album with a picture of a White couple on the cover to enhance crossover and in the late 1970s released Teena Marie’s debut without a photo to obscure her White identity, Motown’s willingness to even visually suggest Washington’s queerness is striking.

Whatever curiosities arose in response to that album cover would be put to rest when the group began, rather famously to perform a cover of Billy Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones,” in concert with Washington clearly singing “Me and Mr. Jones.” Such performances quickly had the Black Press describing the Dynamic Superiors as a “gay” group, as was the case when a 1977 feature on the group in the New York Amsterdam News was titled “Dynamic Superiors Lead ‘Gay’ Music Crusade,” of course begging the question, what exactly is “gay’ music and what crusade was it a part of? (questions that the paper had no intention of answering in 1977).’’

The group didn’t make much of such descriptions; in a magazine article in 1977 (New Gay Life), simply Washington suggested that “I guess it’s because it’s me myself. The fact that I’m the lead singer. I don’t hide it on stage.” Washington’s brother Maurice, also a member of the group adds in the same magazine piece, “It was always there. We just brought it out. Tony was just another member of the Dynamic Superiors…He never did hide.” In an era when no one talked openly about Black queer identity, Maurice Washington suggests that his brother’s willingness to be “out” on stage was empowering to some audience members: “there are a lot more homosexuals there than we think. But they don’t care to let it out. Quite often after the show they want to meet Tony and want to thank him for being as open as they wish they could be…Tony’s a great inspiration.”

However progressive Tony Washington’s band mates may have been in their views about homosexuality — it was in fact his voice that made the group so distinct — audiences were not always in sync. As Washington admitted to The Advocate in 1977, “I guess I was trying to push the clock ahead, though I wasn’t that flamboyant in the beginning…I tried to ease it on them, bit by bit. I thought to myself, man, my makeup is part of the program, so why not accept it.” Washington often made the point, as he did to the Baltimore Afro-American in 1977 that “we are everyday people…we are proud and excited about what we do, but we still have our same friends in Washington.”

The Dynamic Superiors released four albums for Motown between 1974 and 1977. Trying to find just the right musical touch, Motown hired Ashford and Simpson to do production on the first two albums, despite the fact the duo had departed the label in 1973, in part, because the label never saw them as a viable group (Valerie Simpson recorded two solo albums for the label in the early 1970s). Washington and Ashford share similar vocal traits, so a song like the dramatic “Cry When You Want To” sounds like classic Ashford and Simpson, as does “Leave It Alone,” which was later samples by Noel Gourdin on “Better Man” from his debut After My Time.

It wasn’t until their second album, Pure Pleasure (1975) that the group began to broach queer themes in their music. Packaged in the guise of the personal freedoms that marked the 1970s, their cover of the Ashford & Simpson penned Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell classic “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” (a male duet of a song most known as a male/female duet) or a song like “Nobody’s Gonna Change Me,” became anthems for all those working on the margins.

The subsequent decision to gear The Dynamic Superiors towards disco was prescient, if eventually limiting for a group that got its start as a vocal harmony group. The Dynamic Superiors didn’t really reach their audience, in this regard, until their fourth (and last) Motown album, Give and Take, which features with a Disco cover (again) of Martha and the Vandella’s “Nowhere to Run.” The song succeeded in part, because the dancefloor became one of the primary sites where sexuality was being negotiated in the 1970s; seemingly the Disco was the only place where folk had the freedom to come out, given the rampant homophobia of the era, which was manifested in thinly veiled “Disco Sucks” rhetoric.

At the time that “Nowhere to Hide” was released, Motown was heavily invested in Disco music, if only because Berry Gordy was always conscious of the money flow. If Disco was going to dominate the radio, and Philadelphia International Records (PIR) was building an empire, in part because of its role in creating the building blocks for Disco, Motown was, literally, going to be in the mix. Like PIR, Motown was influential in the formative years of Disco; Eddie Kendricks’ “Girl You Need a Change of Mind” (1972) is often cited as the first Disco record and his “Keep On Truckin’” (1973) was one of the label’s biggest singles in the early 1970s.

Additionally, the solo careers of David Ruffin, Diana Ross, Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5 were all re-booted in the mid-1970s with Disco tracks, such as Ruffin’s “Walk Away from Love,” (1975) Ross’s “Love Hangover,” (1976) Jackson’s “Just A Little Bit of You” (1975) and The Jackson 5’s “Forever Came Today” (1975). Indeed, the future trajectory of Michael Jackson post-Motown career was largely shaped by his desire to find his own voice within the Disco idiom.

Given the label’s commitment to Disco — even Marvin Gaye released “Got to Give It Up” — Motown likely placed little significance on Carl Bean’s “I was Born This Way.” In fact, Bean’s version was the label’s second go-round with the song. “I Was Born This Way”, was written by Bunny Jones, and initially recorded and released independently by an artist named Valentino. As the song topped the dance charts in England, Motown purchased the rights from Jones. When Motown botched the song’s promotion — and understandably so — Valentino’s version died, only to be resuscitated a year later by Bean, on a recording that featured veteran PIR and MFSB guitarist Norman Harris and Ron Kersey, who was a member of the Trammps (“Disco Inferno”), to give the song that Philly-Soul sheen.

Carl Bean was not new to the music industry; as an already out Queer Black man, he began his professional career in a Gospel troupe led by the legend Alex Bradford. With the group, Bean had the opportunity to perform on Broadway in shows like Your Arms Too Short to Box with God and Don’t Bother Me I Can’t Cope. By 1974 Bean was fronting a group called Universal Love that was signed to the ABC/Peacock label. The group faltered, as Bean explains in his memoir I Was Born This Way, because the group was “ahead of the curve. I was part of a movement looking to erase the line between R&B and gospel.”

Nevertheless, Bean showed up on Motown’s radar because of Universal Love. According to Bean, in his first meeting with Motown executive Gwen Gordy, she admitted that her brother Berry thought he would be a fit for the song. Besides Harris and Kersey, Motown brought in Tom Moulton for an extended mix, that was marketed directly to Discos, since Black radio stations were unlikely to support the song, even from a valued label like Motown. In the book, The Fabulous Sylvester, DJ Leslie Stoval tells author Joshua Gamson that Sylvester was “informally blacklisted because he was gay…they weren’t ready to give this gay man his place. They didn’t want to deal with it.” Such was the environment that Motown and Bean faced. Nevertheless, without the support of radio, “I Was Born This Way” became a major club hit, that placed Bean on the precipice of major success.

With “I Was Born This Way,” Bean was in position to became everything that Sylvester became, and to their credit Motown was ready to make Bean its next major star, but with a caveat. After Bean signed with the label, he was given the opportunity to record an album that was initially intended for David Ruffin. As Bean recalls in his memoir, the “tracks were smoking-hot R&B. And the lyrics were all about love and ex — love and sex between a man and a woman.” As label executives promised Bean that he could become the next Teddy Pendergrass, he chose to walk away from the deal rather than record songs that hinged on heterosexual desire.

Bean eventually found another calling, one that led him back to the church and into the role as a prominent AIDs activist. The founder of the Unity Fellowship of Christ Church in Los Angeles (which was featured in the Marlon Riggs’ groundbreaking documentary Black Is, Black Ain’t), Archbishop Carl Bean became an important advocate for many communities. Bean’s advocacy provided one of the few Christian-based safe havens for Black LGBTQ communities and he founded one of the first HIV/AIDs hospices in the country. For Bean, his sexual identity and faith were never at odds, as he explained in a 1978 magazine article that “it’s God’s way of making a statement through me…it’s something that should have been said a long time ago.”

One wonders if Carl Bean and Tony Washington ever crossed paths at Motown; Washington is rumored to have died from AIDs, after the Dynamic Superiors broke up in 1980. Bean and Washington’s legacies will forever be linked, reminding folks of the time when Motown was not only the “sound of Young America,” but perhaps the “Sound of Queer America.”

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.