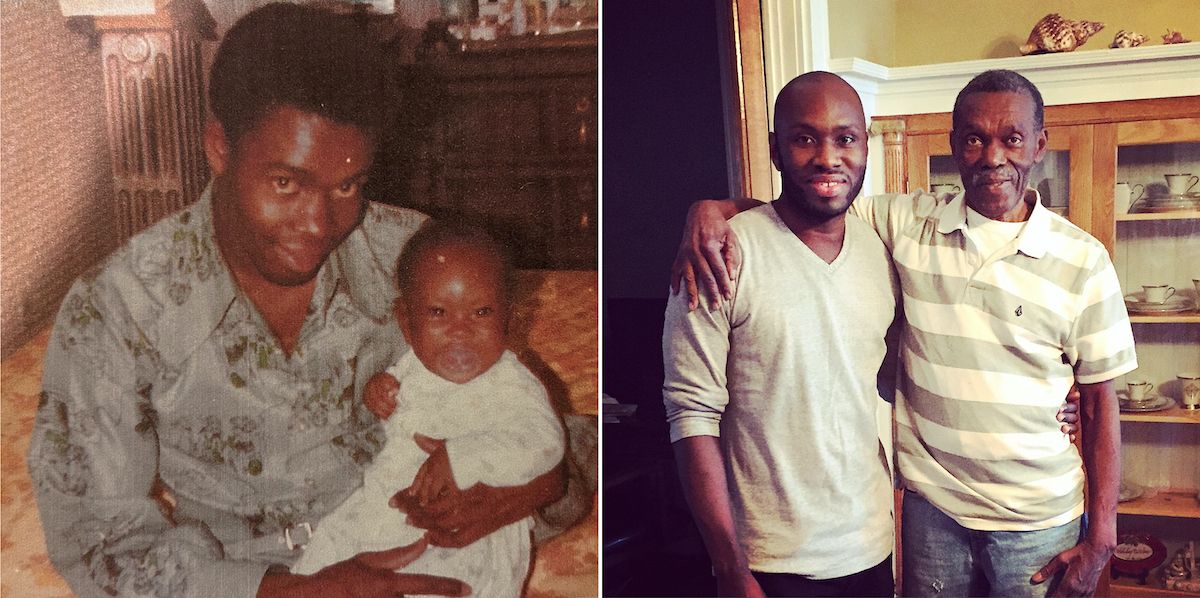

My father never hit me. He never yelled at me. Never smothered me in toxic masculinity. And for that, I’ll be forever thankful. Still, that doesn’t take away from the fact that from birth to about the age of 22, I only have six substantial memories of my father—forgotten infant and early elementary years excluded. In my adulthood, our relationship became even more strained, as we never forged a true connection. And now that he's passed, I'm left picking up the pieces and reckoning with the loss of a parent I never truly knew.

Since the turn of the century, I’ve seen my father in person three times. The first took place in 2015 during a New York layover he was on; the last was during a 2018 family trip out West. With my father settling in California after retiring from the Army, distance played a role in our lack of physical time together. But the cost of an occasional plane ticket shouldn’t be a barrier to being present as a parent. Where there’s a will, there’s a way, as the adage goes.

My father attempted to patch the lapses between our IRL interactions with sporadic phone calls. In my youth, I looked forward to these occasional chats in which he’d make various unfulfilled promises and attempt to explain the governmental benefits I could enjoy as the son of a veteran. As time went on, the dynamics of our telephone interactions continued to evolve.

By the time I graduated college, these calls with my father were less hopeful and instead layered with suppressed anger on my part. It all started in the fall of ’99. After more than a decade apart, we had an uneventful meet up when I was in California for a press junket. Prior to that day, I always held on to the idea that once my father and I had a chance to meet as two grown men we could forge some sort of meaningful relationship. Instead, I was deeply wounded by the reality that I had flown 2,902 miles just to eat by myself at Subway while my father hung out with his friends barely 30 feet away. From that moment on, he was cut off in my mind—I just never verbalized those feelings.

As much as I wanted to avoid talking with my father, my biggest fear was that he would someday die and I’d be forever stuck with unspoken resentment [and] I’d never have the closure I desperately needed and deserved.

Over the next several years, my father’s infrequent calls were tolerated but never really welcomed. He had a chance to make things right or at least start the process that day in Cali and he blew it big time. After that crushing disappointment, whenever I saw his name illuminate on my phone, I felt an anger building up in me. Talking to him felt like being raped emotionally: I didn’t ask for these calls, his voice just penetrated my eardrum at his discretion so he could feel good about himself. Speaking with him was excruciatingly uncomfortable. His words were hollow and had no value to me. It didn’t matter what he had to say, I’d just uh-huh my way through it until he was done. All I wanted was to get off the phone and back to my life, the one that was perfectly fine without him. At least that’s what I told myself.

This went on for about eight years. Every few months, my father would pop up before disappearing for an equal or extended amount of time. My hope would be for the latter so I could continue living my life without these unrequested interruptions for as long as possible. But as much as I wanted to avoid talking with my father, my biggest fear was that he would someday die and I’d be forever stuck with unspoken resentment. If I allowed him to leave me carrying all of this emotional baggage, I’d never have the closure I desperately needed and deserved. I knew I had to let him know how I felt and why. But there’s a big difference between wanting to do something and actually mustering up the courage to do it—especially when it’s related to the source of lifelong trauma.

I finally addressed our issues at the tail end of 2006, on my 30th birthday. When my father called to wish me well, I let him know how I’d felt for much of my twenties. I expressed how his mishandling of my aforementioned visit to California truly hurt me. I expected excuses, gaslighting, and more broken promises. Instead, his response was accepting, accountable, and dare I say empathetic. He fully acknowledged that he hadn’t been there for me or my brother like he should have. He owned up to his part in our fractured relationship. And for the first time in my life, we had a real conversation.

I’d be lying if I said things instantly turned around after that convo. Truthfully, his subsequent reach outs still ignited my anger but my heart was more open to hearing him out. Over time, those negative feelings began to wane. We’d never be best friends, but we could be friendly at best.

By the time I became a father in 2016 our calls had become cordially productive. I even opened the door for my father to build a relationship with my daughter. Throughout the pandemic, my father called semi-religiously on Sundays to FaceTime with me and his granddaughter, who he affectionately called “Miss Ella.”

Despite the frequency of the calls, though, my father wasn’t much of a conversationalist. He tended to talk at me more than to me. He’d run through the usual mundane aspects of his day: having to wash his truck, going to visit his best friend, calling other family members later in the day. We rarely dug beneath the surface and had any heartfelt conversations that gave insight into who he was beyond the crib notes I’ve gathered over the years.

Now it’s too late. The day after Christmas, I found out my father died alone in his apartment. Apparently he had passed earlier in the month, but it took a week for anyone to notice. After spending the previous month and half in the hospital, he was supposed to be on the road to recovery. But life had other plans.

It’s eerily ironic that the news of my father’s passing would get to me on December 26, which happens to be my birthday. It was 16 years ago to the day that I had voiced my resentment to him, and now it marks the end of our chapter, which has given me a lot to think about.

Essentially, my father was still a stranger to me. No matter how far we had come, he was more of a distant relative than a close family member or even a friend. Most of what I know about him is based on secondhand stories that never put him in the best light: an alcoholic, a womanizer, a habitual liar. His absence and empty promises to me did little to shift the narrative.

Now, in the wake of his passing, I’m forced to deal with various long-lost relatives and friends emerging with new stories about him that ebb and flow between positive and negative narratives. I’ve always said no one person truly knows you 100%. Everyone with whom you interact has their own experience; only when you compile those various interpersonal dynamics do you finally get the full picture of a person.

As a journalist, you’re trained to be objective. I’ve been trying to apply the same consideration to my father. I’m warming up to the idea that in his final years he was a different man than the one I’d long perceived him to be. This is no revisionist history—there’s no doubt that he was an inadequate father. The man I experienced for most of my life was not loving, helpful, nor present. But I can acknowledge there was more to him, especially when I consider my daughter’s perspective.

My daughter cried upon learning of her grandfather’s death. I honestly didn’t expect that kind of emotional reaction from a 6-year-old. They had only met once when she was too young to remember, and all their subsequent interactions were a couple minutes here and there via FaceTime. But to her that was Grandpa Sammy, the only grandfather she’s ever known. Through my daughter and the impact my father made on her in such a short period of time, I’m able to see an aspect of him I thought didn’t exist. Thanks to virtual communication, my daughter experienced a side of my father that was consistent and present. He may have sucked at parenting me, but at least he was a decent grandfather. At the end of the day, I can live with that because it’s not always how you start that matters but how you finish.

My relationship with my father may have been a work-in-progress, but it was working, nonetheless. I’m thankful that he allowed me the opportunity to unload those years of hurt so I don’t have to carry that with me now that he’s gone. There are still lots of unresolved feelings to unpack, but at least I can do so without any anger or hate in my heart for my father. The past he and I shared can never truly be forgotten but I’m happy to say that it can be forgiven. It may have taken 46 years but I’m at peace with my relationship with my father and I’m hopeful that he can rest peacefully with that as well.

More From LEVEL: