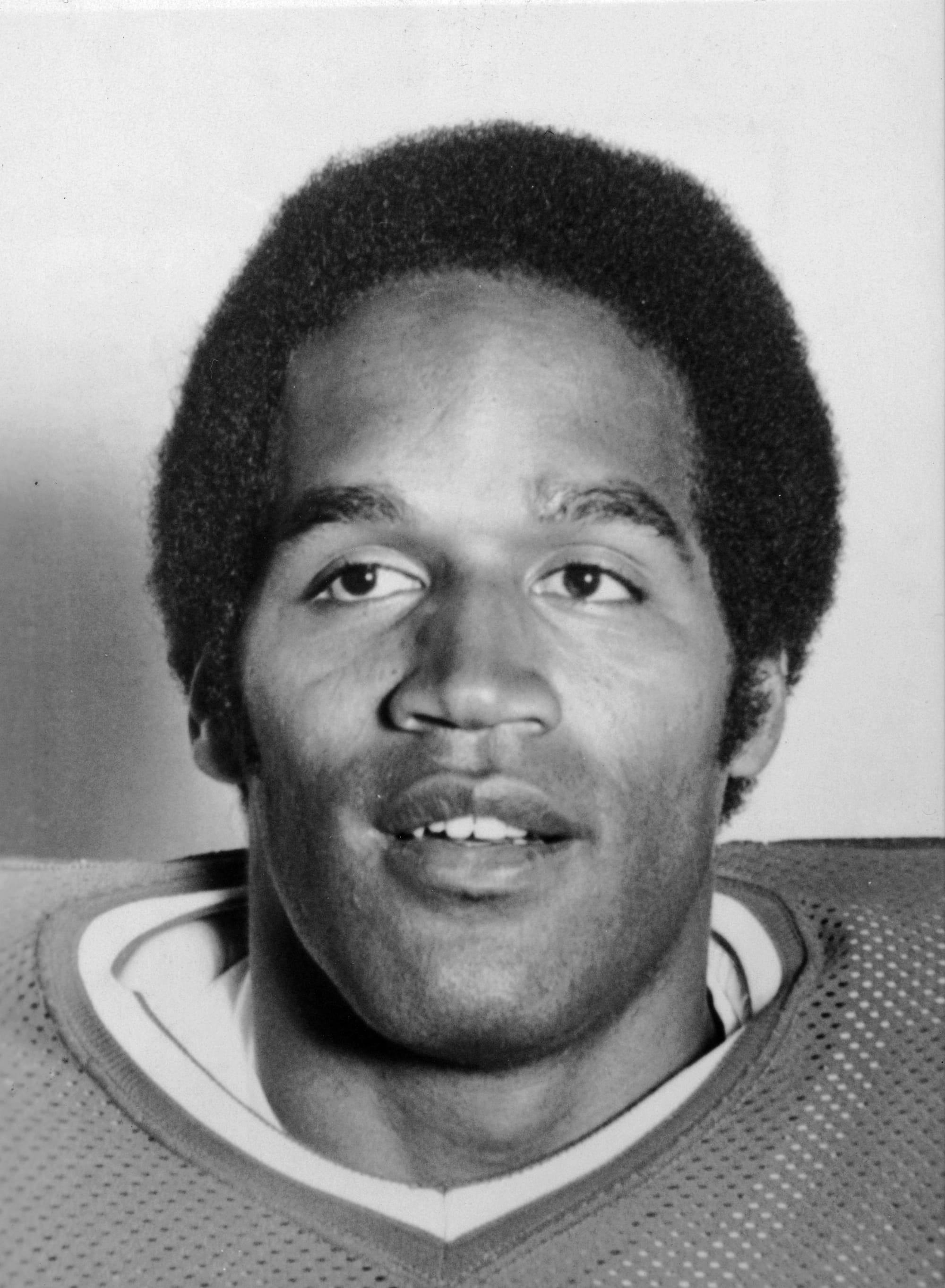

Unless you are of a certain age, you don’t really know Orenthal James Simpson; you know only what people have told you about him. He was one of America’s greatest athletes, yet at an early age, he battled with rickets and wore braces on his legs until age five. Ironically, one of the treatments for rickets in children was vitamin D and calcium supplements found in some versions of orange juice. If you didn’t know, you’d think his nickname was associated with the orange juice commercials O.J. did so well after he retired. The Juice nickname was associated with electricity, and his offensive line while playing with the Buffalo Bills was The Electric Factory.

O.J. had troubles as a youth; he was a member of the Persian Warriors gang in his hometown of San Francisco. Police stopped him for petty offenses like stealing beer and fighting. Simpson spent a weekend in juvenile detention when he was 16 as a deterrent and he was arrested at least three times. Officers didn’t want to disrupt a football career that it was hoped could change his direction. An arranged meeting with San Francisco Giants baseball star Willie Mays helped him see the light.

In 1965, O.J. graduated from Galileo High School in San Francisco, where he played football, and enrolled at City College of San Francisco, where he joined their football team. Two years later, he transferred to USC, where he was twice an All-American, not before marrying his first wife, Marguerite Whitley. In 1968, he became USC’s second-ever Heisman Trophy winner. He set the NCAA single-season rushing record that season and equaled or bettered 19 NCAA, conference, and USC records.

The hype surrounding O.J. in college is impossible to relate to today. There were three television networks and no cable TV. College football was king and had no competition on Saturdays when most games were played. Many of USC’s games were televised, and when on television, O.J. always performed. Whatever you thought of Herschel Walker at Georgia, Bo Jackson at Auburn, Earl Campbell at Texas, Archie Griffin at Ohio State, or Barry Sanders of Oklahoma State. None of them captivated the nation more than O.J. Simpson, who became the №1 Draft Pick of the Buffalo Bills and took his talents to the NFL.

In 1969, Buffalo was considered the NFL's hinterlands. The three networks constantly showed the top NFL teams or those from the largest cities. Televised games rotated between the Dallas Cowboys, Los Angeles Rams, Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers, Cleveland Browns, Philadelphia Eagles, Minnesota Vikings, and San Francisco 49ers. The NFL was completing a merger with the AFL, and 1970 would be Buffalo’s first year of competing in the combined league. Nobody outside the Buffalo area was all that interested in the Bills, but for the presence of one of the league's most exciting running backs. In 1973, Simpson broke the league's single-season rushing record and was the league's MVP.

America tuned in weekly as Simpson raced toward a never-before-achieved 2,000 yards rushing in a single season. Simpson finished the 1970 season with 2,003 yards rushing in 14 games, surpassing Jim Brown’s record of 1,863, averaging 143.1 yards per game, which is still the NFL single-season record. Simpson is in the discussion as the best ever to play the game. Seven other men in NFL history have rushed for 2,000 yards. None accomplished the feat in a 14-game season like O.J.

Related: Here's a Look at O.J Simpson's Career Highlights in Football and Athletics

Simpson was coming off a period where he’d been honored as the best player in college football and the most valuable player in the NFL. He was handsome and articulate, and his time at USC exposed him to the television and movie industries. He appeared as a potential LAPD recruit on Dragnet before ever lacing his cleats at USC. Simpson began appearing in television commercials for Hertz Car Rental Company, where he was seen running through airports and sipping on beverages like RC Cola and TreeSweet orange juice. When his football career ended, finishing second at the time to all-time rushing leader Jim Brown. Simpson started appearing in films, including Capricorn One and the Naked Gun series. O.J. was not only a star; he was also the star—one of the most famous athletes in the world at the time. Simpson changed America’s viewing habits and increased NFL ratings to put it on pace to exceed baseball as the nation's most popular sport.

Everybody loved O.J. when he retired from the San Francisco 49ers in 1980, where he spent the last two seasons of his career. One possible exception was his wife Marguerite, whom he divorced in 1979. They had several separations during their marriage, though the causes were unknown. Marguerite told 20/20 host Barbara Walters in 1995 that she was “willing to testify” that OJ never hit her during their relationship. The year after their divorce, their daughter Aaren, the youngest of three children, drowned in their Brentwood home a month shy of her second birthday. OJ probably thought this would be the worst of times he’d experience.

Six years after Aaren’s death, OJ married Nicole Brown, with whom he had two additional children. The marriage appeared sound on the outside, but few outside the LAPD knew of the multiple times the police were called to the Simpson home after reports of abuse by Simpson. He was usually given a warning but not hauled in. On May 24, 1989, OJ was sentenced to two years probation and 120 hours of community service for spousal abuse. One of the ways Simpson changed America was its response to domestic violence. Doing nothing was less of an option after the national exposure, given the lack of action by the LAPD.

O.J. and Nicole separated in 1992. They still saw each other because they shared two young children. On June 12, 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were found dead outside her Los Angeles home. There was a lot of media speculation about Goldman’s relationship with Brown, but it appeared that while the two were friends, he was simply returning a pair of sunglasses Brown had left at the restaurant where he worked. The funeral was held in Los Angeles on June 16, 1994. OJ attended with the former couple’s two children.

The media was full of speculation, and on June 17th, Simpson was charged with the two murders. OJ was supposed to turn himself in but didn’t. Simpson drove away in his white Ford Bronco, leading to a 60-mile slow-speed chase shown live on TV, accompanied by his friend Al Cowlings, who was driving. It was reported OJ had a gun and was suicidal. They eventually parked at OJ’s mother’s home, sitting in the Bronco for two hours before Simpson gave himself up.

The OJ Simpson trial was one of the biggest media spectacles ever. You may have watched the first nationally televised trial of Ted Bundy, maybe the Casey Anthony trial, the Menendez brothers, the LAPD officers that beat Rodney King, or that of Alex Murdaugh. However, the Simpson case changed how we watched televised trials and helped establish Court TV. Careers were made, and we now knew the names of prosecutors, lawyers, witnesses, and the judge, with their performances reviewed nightly. The defense attorneys were nicknamed the Dream Team, the judge indecisive and the prosecutors every move questioned.

Related: How O.J. Simpson's Murder Trial Changed the TV News

As the nine-month trial progressed. Opinions as to Simpson’s guilt started to form along racial and ideological fault lines. By the end of the trial, most white people polled felt Simpson was probably guilty and received a fair trial. More Black people than not felt the trial was unfair and that Simpson was innocent.

I had a chance to interview several Black people today, old enough to have watched and remember the trial. The common belief was that OJ was probably guilty, but to a person, they felt the trial was unfair and that the LAPD had planted evidence and lied.

They didn’t have to be reminded about Detective Mark Fuhrman, who, at minimum, perjured himself about ever using the word “n****r.” An audio tape revealed 40 times Fuhrman used the word, with the transcripts proposed to be read aloud in court. Here are ten examples from the 40:

1. ( . . . speaking of changes in composition of L.A.P.D.).

“That we’ve got females . . . and dumb n*****s, and all your Mexicans that can’t even write the name of the car they drive.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p.11.)

2. ( . . . speaking of the physical risks to officers).

“If I’m wrestling around with some ___ n****r, and he gets me in my back, and he gets his hands on my gun. It’s over.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p. 12)

3. ( . . . describing arrest of a suspect).

“She was afraid. He was a big n****r, and she was afraid.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p. 20)

4. (. . . explaining arrest of a suspect in Westwood).

“He was a n****r. He didn’t belong. Two questions. And you are going: Where do you live? 22nd and Western. Where were you going? Well, I’m going to Fatburger. Where’s Fatburger. He didn’t know where Fatburger was? Get in the car.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p.33)

5. (. . . commenting on L.A. P. D. politics).

“Commander Hickman, was a d******d. He should be shot. He did that for one thing. He wants to be chief, so he wants the city council, and the police commissioner, and all these niggers in L.A. City government and all of ’em should be lined up against a wall and f*****’ shot.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p.41)

6. (. . . discussing American aid to drought victims in Ethiopia).

“You know these people here, we got all this money going to Ethiopia for what. To feed a bunch of dumb n****** that their own government won’t even feed.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p. 44)

7 & 8 (. . . discussing where he grew up in the state of Washington).

“People there don’t want n****** in their town. People there don’t want Mexicans in their town. They don’t want anybody but good people in their town, and anyway you can do to get them out of there that’s fine with them. We have no niggers where I grew up.”

(McKinny Transcript №1, p.45)

9. ( . . . speaking of women as training officers).

“When I came on the job all my training officers were big guys and knowledgeable, some n*****'d get in their face, they just spin ’em around, choke ’em out until they dropped.”

(McKinny Transcript №1., p. 47)

10. (. . . discussing use of chokehold by L.A.P.D.).

“No, we have to eliminate a choke hold because a bunch of n****** down in the south end of L.A. said this is bad.”

Judge Lance Ito decided that only two uses of “n*****” would be read to the jury, and none of the 18 excerpts from the tapes in which Fuhrman talked about planting evidence, beating suspects, and committing perjury. The jury would barely hear about Fuhrman’s use of the word, but Black Americans watching television coverage knew all about the transcripts.

Mark Fuhrman did more to impact Black attitudes about the trial than any piece of evidence, including the infamous gloves that didn’t fit. Black people may not have known if OJ was innocent but believed wholeheartedly that police in Los Angeles and elsewhere would plant evidence and lie, as Fuhrman alluded to about other cases in the tapes.

Media coverage about the transcripts couldn’t very well keep broadcasting the word “n*****” on national television on the 5:00 news. Instead, they gave us the diluted version, “the N-word,” as a substitute, which is widely used today.

Related: In the Land of Whiteboys Who Use the N-Word

On October 3, 1995, OJ Simpson was acquitted of the murders of Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman. There was widespread reaction along racial lines, but the Black reaction, with many people cheering the acquittal, needed a little explanation. It was because Black people were so accustomed to seeing what they perceived as unfair verdicts. The acquittal of the four officers who beat and stomped Rodney King that set off the Los Angeles Riots was fresh in Black minds. Mark Fuhrman’s testimony was etched in our brains. It was the one memorable time in recent times in America where a Black man faced the justice system and won, so we cheered.

As an aside, Mark Fuhrman was ultimately charged with perjury. In 1996, he pleaded no contest and was given three years probation and a fine. Fuhrman wrote seven books and became an expert consultant for Fox News.

Though found not guilty, Simpson was hounded for much of his life. A civil suit filed by Ron Goldman’s family found Simpson liable in the deaths of Goldman and Brown for $33 million. According to Goldman family lawyers, OJ has paid only $133,000; with interest, he now owes over $100 million. This inability to collect led several states to require losers in civil suits to post bonds to ensure the collection of funds.

In 2007, Simpson and the five men he hired attempted to retrieve some memorabilia from dealers in Las Vegas he accused of stealing from him. Simpson and one of the men were later charged and found guilty of kidnapping, armed robbery, assault with a deadly weapon, burglary, and conspiracy charges. The other accomplices had taken plea deals and received probation. Simpson was sentenced to 33 years in prison for his role in the botched hotel room heist, serving nine before his parole in 2017.

On April 10, 2024, OJ Simpson died of complications from prostate cancer at age 76. Many people will always be convinced of his guilt in the murders; others will say the 33-year sentence for getting back his stuff was retribution. None of the people I talked to seemed sad about his death. The ones who felt one way or another about his guilt weren’t inclined to argue their point. They were ready to let it go and move on. Maybe that’s the way it should be.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.