A real man can admit when he’s wrong, so here it is: I fucked up. But she didn’t have to come at me like that, yo.

I never really got along with my project manager, Shereene. Which was a shame, because she’s also a person of color, although she’s not Black. The issue was that she addressed me differently than she did other co-workers — she tended to be curt with me, even callous — and it was so obvious that a lot of my colleagues picked up on it too. I couldn’t help but suspect there was some racial bias at play.

My fuck-up wasn’t even that serious. I’d mistakenly double-sent a marketing email out to prospective customers. An honest mistake, minor as things go, and I owned up to it. As per the protocol for those situations, I emailed the leadership team explaining the incident in a detailed brief, identifying who was affected, and outlining next steps. The only real point was to have a record that everyone had been updated, and keep it moving.

A few minutes pass. Then, ping! An email from Shereene, with all of the higher-ups CC’d — a classic aggressive-aggressive gambit in the corporate world — criticizing the way I… [looks again at email] formulated my brief?

Gimme a break. It was a subjective disagreement, if not a totally bullshit microaggression, and it felt like she was attacking me to try to make an example. I’d already corrected the double email issue, but her feedback made me second-guess myself. Did I actually misstep? Was I really in the wrong?

Even better, she topped her arbitrary critique with an extra scoop of condescension. “If you need any help, just reach out to me — that’s what I’m here for.” As if I need any help following a simple template. (Seriously, it’s basically a Mad Lib with some marketing jargon thrown in.)

Just my luck: a gaslighting-patronizing two-for-one special! Finally, I understand why dudes freeze their asses off six times a day in the smokers’ circle outside.

As a Black person or person of color in this type of environment, you’re always going to be dragged into some shit.

I checked the temperature of the situation with my team; everyone agreed that I had acted in an appropriate manner. “I don’t understand why this is becoming a bigger issue than it really is,” one of my (White) co-workers said. I’ve got a theory, I thought, but it was best to keep the race card tucked away for a more extreme scenario.

I’d previously trained with someone else who’d worked with Shereene. He was a positive, passive guy, who emphasized this one piece of advice: Don’t get involved with workplace politics. I tried not to, but as a Black person or person of color in this type of environment, you’re always going to be dragged into some shit. Otherwise, you’d have to act as a passive person and just brush everything off. And there’s always something — just ask my therapist.

Not too long before the Shereene situation arose, my roommate — a Black woman — had said something that stuck in my head: “I’m hireable, and I’m fireable.” I could hear those words again when I decided to speak up, like a mantra of empowerment.

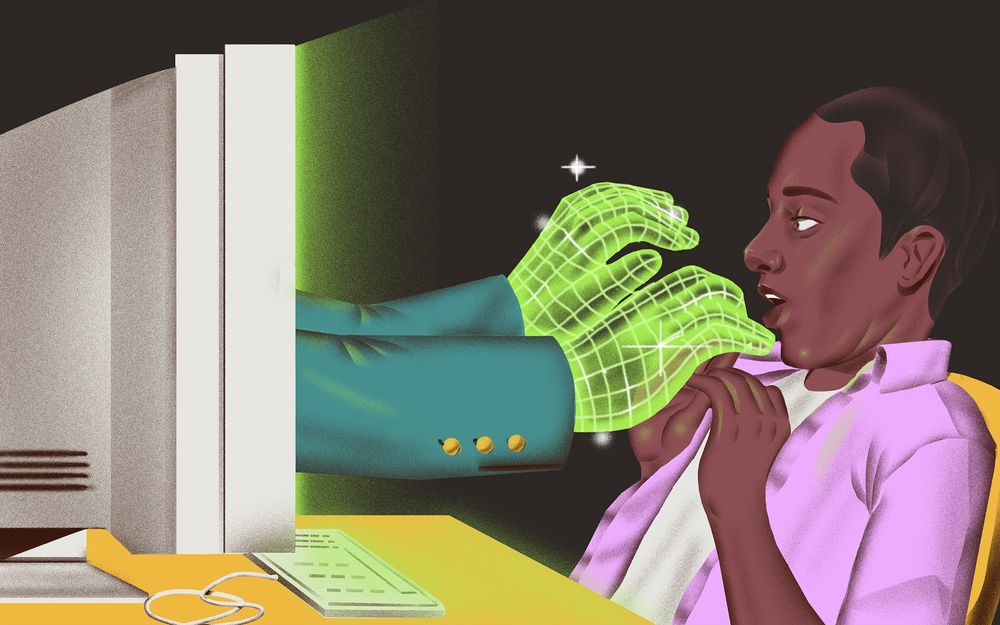

This was an opportunity to use my voice, and to do so as smartly as possible. I learned long ago not to underestimate the value of a paper trail — word to T.I. So, I wrote to my supervisors: “I don’t know if this is how she normally talks to people but it doesn’t feel like constructive criticism.” It was documented, and the whole thing ultimately blew over.

It wasn’t my last run-in with Shereene, of course. The next time I had to file a brief, I took her up on her incredibly helpful offer to make sure I was following protocol. Her response was dismissive, and basically boiled down to: “Why would you ask me this?” There goes that gaslighting again.

I forwarded that response to my supervisors, with a message that was formal, corporate-coded ether. “I find this to be strikingly inconsistent, inappropriate and highly counterproductive,” I typed, the keys click-clacking with righteous fury. “It makes me not want to come to her for anything.”

I was anticipating being thrown under the bus, removed from the project, or even out of a job, just another colored corpse of the corporate world. Instead, my supervisors came through. “We have read everything,” they responded. “We see you. We hear you.” I nearly spit black coffee onto the MacBook screen. I was shocked, although I couldn’t help but wonder whether sexism played a role in these White dudes’ support — or the fact that Shereene and I are both people of color.

I’m sure there were conversations happening that I wasn’t privy to, but documenting the issues helped them to work in my favor. Ultimately, I was transferred to a different project manager, which was great. That role had its own issues — we were expected to be deferential with clients in a way that was a little difficult for me — but at some point, work is work. We’re all human, for Chrissake.

I’m grateful for that experience, though. I’m sure there were folks who had come before me who either didn’t know how to speak up in those situations, or were afraid to — but at that point, I honestly didn’t really care about my fate at the company. I know my worth and know that, should the worst-case scenario unfold, I’d be an asset elsewhere.

I might be fireable, but I damn sure know I’m hireable.