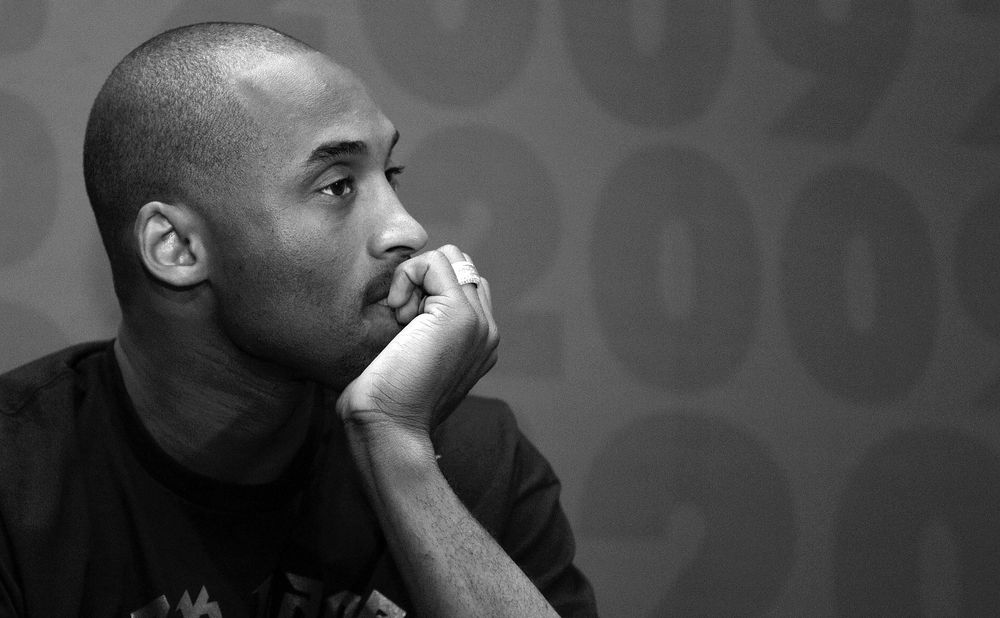

A year after Kobe and Gianna Bryant’s sudden death, it still feels like an open wound. Some people are able to remember exactly where they were when they heard the news. That’s not the case for me. What I remember is the feeling: first apprehension, then a visceral pang as my heart sank into the soles of my feet. I do remember, quite clearly, a gap in both time and information when news filtered out about the helicopter crash. In that weird temporal displacement, we faced possibilities that ranged from dubious (that this whole thing was a TMZ farce) to utterly heartbreaking (that both Kobe and his daughter were indeed on the aircraft).

Once the news was confirmed, his colleagues were, like the rest of us, stunned. Shaq immediately posted a photo of the big man newlywed-carrying Bean during their dynasty run. On court, NBA players committed intentional turnovers in honor of Kobe’s retired jersey numbers: eight-second violations for not advancing the ball across half-court, 24-second shot clock violations. “I know you said keep going,” wrote Dwyane Wade, the player most like Kobe than anyone outside Michael Jordan, “but today, we can’t.” Wade echoed the world. This was one of the few times the royal We could be used accurately. We all just stopped, digesting deaths that didn’t feel real.

Weeks, months after his death, Kobe continues to trend on social media platforms regularly, but never with the irreverent tone other popular topics received. He’s always revered. He’s always the role model. He is the girl-dad, the hustler, the teacher and student. That sanctity extended to his fans’ grief, which didn’t receive the questioning or interrogation that others did when remembering high-profile Black men felled by tragedy. Nipsey Hussle disciples saw their #MarathonContinues hashtags and philosophizing become fodder for memes and clownage; that didn’t happen with Kobe. And why it didn’t may just speak to something larger.

It’s an uncomfortable thing, to realize that uttering one word about the case these days will engender anger from fans. Now that Kobe Bryant is gone, though, pretending it never happened betrays the man’s life, and whatever journey he wanted us to observe.

How we talk about Kobe Bryant is at once a result of admiration, celebrity worship, and acknowledgement of a man who molded his own legacy — from genetic gifts, yes, but more so from the sheer will to surpass even his biggest influence, Jordan. His story, although it spanned the world, felt very simple to track. He learned to play in Italy, moving to Philadelphia as only a teenager, at least partially for the opportunity to play in the NBA. He sparkled as a high school player, but there was always something different about him; he played with other Philly teens but wasn’t like them. He was both an outsider and a baller, and the combination made him special.

It also meant that Kobe was always seen through an international lens. The narrative’s love of his speaking Italian highlighted the privilege of his basketball family, an alternative vision to the streetwise, tatted-and-plaited Allen Iverson. His Blackness mattered, but his Italian acculturation insulated him from some of what Iverson had to deal with; race wasn’t used against him in the same way. He grew the fro, gritted his teeth through the early difficult years, became a champion and superstar. He was never truly hated by the media. Teammates would remark that he was harsh and domineering — in mimicry of his idol — but sports pundits love that kinda shit. It showed that he was willing to do whatever it takes to win.

After his passing, players and fans still honor the Mamba mentality. Unlike The Marathon Continues, though, Kobe’s philosophy hasn’t spawned memes ridiculing its abstraction or imagining how adult Black men are probably teaching those very same abstractions to their kids. And it’s not like people didn’t try: The young chaotic minds of TikTok definitely attempted to get their jokes off, but were almost immediately cut off by grieving critics, Kobe fans, and trolling commenters. Kobe Bryant is off-limits, as he has been (at least in the eyes of the media and public consciousness) for many years.

The first time that reverence was put to the side was in the summer of 2003, when Kobe Bryant was accused of sexually assaulting a 19-year-old woman in Colorado. It was the first time someone — the burgeoning blogs, news media, other players, comedians, and damn near anyone else — had the power to knock the Mamba down a peg. That year, Kobe Bryant was on the lips of damn near every barbershop patron around.

We know how that story ends. But a few crucial details are important to how our perceptions of Kobe were both individually projected and collectively pervasive.

On the occasion of his 2016 retirement, a ThinkProgress article catalogued the ways that the media and Bryant’s defense team pounced on the young woman, engaging in “victim blaming, media sensationalism, and image repair” from the moment charges were filed against Bryant until the settlement was reached and Kobe issued an apology. As Lindsay Gibbs wrote, the woman’s biographical details were weaponized almost immediately:

“She was a sexually active teenager who had attempted suicide twice and been briefly hospitalized for mental illness. She was an aspiring singer who had once tried out for American Idol. She had a lingering crush on her ex-boyfriend. So very quickly, a picture was painted of a fame-hungry, unstable woman who would do anything for attention.”

Gibbs detailed how Aurora University psychology professor Renae Franiuk examined the media coverage of the Bryant case, and found that more than 42% of articles questioned the victim’s honesty — and fewer than 8% questioned Kobe’s. That dynamic had a predictable effect: As Gibbs wrote, readers who were more exposed to the outlets that smeared the accuser were “far more likely to side with the accused than the alleged victim.”

As her mental state and capacity to defend herself deteriorated, the young woman opted for a closed-door settlement. As part of that, Kobe wrote an apology that, read today, does actually provide some insight into the lacking education around what consent is. But the ordeal as a whole lacked that sort of contrition. It felt like Kobe trying to put this thing to bed like a dagger three in the fourth quarter.

He succeeded, mostly. People made their jokes, but Kobe balled out during the season after the case. He led the league in scoring, and with the civil case being handled more privately, he and the rest of us could be focused on our comforts — watching Kobe ball out.

As time went on, Bryant raised two daughters and reconciled with his wife, Vanessa. He repaired his image by winning two more chips because, as sports pundits also like to say, winning cures all. And now, when a journalist with the stature of Gayle King asks Kobe’s friend about dealing with that particular paradox, Snoop Dogg calls her “funky dog-haired bitch” to his millions of followers on Instagram, thus concretizing the gag order on this particular topic.

It’s an uncomfortable thing, to realize that uttering one word about the case these days will engender anger from fans. Now that Kobe Bryant is gone, though, pretending it never happened betrays the man’s life, and whatever journey he wanted us to observe. The arc that he penned may have enjoyed the media (and later, social media) as a co-author, but it should also be told in full. Kobe had his own truth, and perhaps his growth was manifesting in all of these relationships, but we have to remember that this is still just a slice of his world. The one he wanted us to see.

Kobe’s image rehab took place early, but his character repair — the self-interrogation he would have to undergo in order to really change — took a lot longer. We watched as it happened, as Kobe aged right in front of us. We watched him attend WNBA games, watched him support basketball all across the world played by all types of different people. He made movies, he taught the game. He was everywhere. Loved everywhere and by all… except by sexual violence survivors whose thoughts, concerns, and voices played very little role in how he’d be remembered.

And now, aided by some collective social media omertà, Kobe Bryant’s mentality persists. Not the Mamba mentality that preaches grit and intensity at the workplace and at home, but the philosophy that says you can mold your legacy to fit the reality you have for yourself. Even if it’s not entirely the truth.

Like many people, I’ve got a sports-related group chat going. Last week, when I told mine — all college friends — that I’d be writing about Kobe this week, the responses were tough. “Mourning usually takes years,” one homie said. “Kobe still hurts. I still can’t watch any of the videos of him that’ll pop up on my feeds. Still too raw.”

“Yea I be gettin sad too,” another said. “But also hopeful. It’s weird.”

Why hopeful?, I wondered.

“Just feeling like he meant so much to so many people and has inspired countless people to reach their goals,” he replied. “Like his life carried actual meaning beyond what he meant to me. I find that encouraging. And hope to make a similar impact even if on a much smaller scale.” He didn’t mention the rape case at all. I wasn’t expecting him to.

The more I think about it, the more “hopeful but weird” feels apropos. I’m altogether hopeful that the truth of Kobe’s life was closer to the slice he showed us in his later years. We want to believe that what happened in Colorado was an aberration — a moment of weakness and ill education around sex and consent. But it’s hard to tell whether that desire comes from anything more than the hope that Kobe provided people in their daily lives to overcome whatever struggle they saw in it.

Kobe Bryant, bless his soul, is long gone. Despite his indelible legacy on the court and the impact he may have had later on, he is dead. That woman, though, is still with us. The innumerable survivors of sexual violence are still with us. How we talk about Kobe from here, if we are to talk about him in truth, has to include the living, breathing reality that his celebrity gave people a reason to silence survivors. For all those who, like the survivor in his particular case, tried to keep going but just couldn’t.