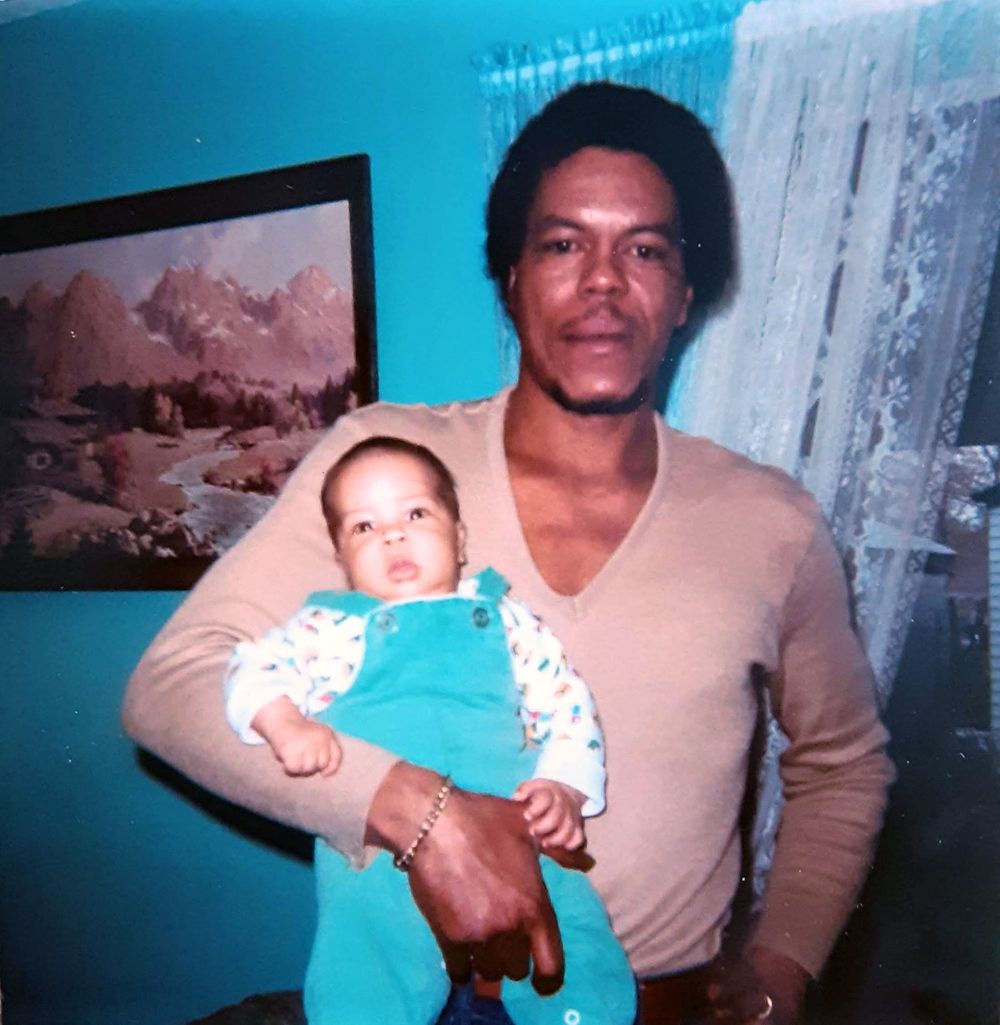

I used to think my father looked like Marvin Gaye. I’m talking about the Marvin of the ’70s, the What’s Going On/Trouble Man Marvin, the “I come up hard, baby, but now I’m cool / I didn’t make it, sugar, playin’ by the rules” Marvin. The denim-on-denim Marvin, with the two-month-old beard, the heavy-lidded eyes, and the devil-may-care grin. I used to study Marvin’s album covers while listening to his records in my bedroom, and I’d flip out over how much he and my old man looked alike. I was probably a little generous in my estimation. But if you’re a young, Brown boy whose father isn’t often around, older Black men — especially handsome and talented ones — tend to wield great power over your imagination.

I was born 40 miles west of Detroit, the birthplace of Motown Records. My parents divorced when I was a toddler, and I lived with my mother in Ann Arbor, while my father moved back home to Ypsilanti, a working-class city between the two. My father is dark Brown, had a cool swagger, smoked menthol cigarettes, and drank from brown paper sacks. My White, Jewish mother, bless her soul, listened to Joni Mitchell and Sarah McLachlan. Though I lived with my mother and went to school down the street from our house, Fridays after school she would drive me 10 miles to Ypsilanti and deposit me at my father’s house for the weekend.

My father was named after his father, Woodrow Holley, but nobody called my old man Woodrow. Folks called him Pot, a nickname he’d been given as a boy. Every weekend he would march me around Ypsi, making the obligatory visit to Floyd and Bo and Miss Genie and Miss Bullock and a nonstop parade of cousins, and they’d call me Lil’ Pot and tell me how much I looked like my old man. I’d smile and shrug, then we’d go on to the next house. In addition to the overflowing ashtrays and plastic-covered furniture and velvet paintings of naked Black women with towering Afros, there were always records spinning in these houses. These weren’t the records that played at my mother’s home. This music was vibrant, jubilant, dangerous, seductive, carnal, alive. This was grown folks music.

I imitated their attitudes, their mien, their ‘soul brother’ jive. Not until I reached my midteens did I realize these singers had been more to me than entertainers, teachers, or elders; they had been surrogate fathers.

After we’d finish our obligatory tour through Ypsi, my father would buy me a Faygo Redpop at the party store and drop me back at his house to watch TV while he went off to attend to his own business. He’d come back late at night, smelling like gin and passing out in his bed. It didn’t bother me none. Drinking was just what he did. Some fathers tinker on old cars, some wake up early and go fly fishing or grouse hunting; my old man drank cheap gin and played dominoes with his friends. It’s all good, let the man have a drink.

But after my mother would pick me up Sunday evening and shuttle me back to Ann Arbor — bringing me back to the world of townhouses, station wagons, and grilled cheese sandwiches — I’d realize another weekend had passed without my father and I forging any real connection. He was someone I resembled close enough for folks to comment on week after week, but he largely remained a stranger. He neglected to school me in what it meant to be a man, let alone a Black man in America. So I looked to music: Marvin Gaye, the Isley Brothers, Gil Scott-Heron, James Brown.

“Make me wanna holler, the way they do my life.”

“Time is truly wastin’, there’s no guarantee / Smile is in the makin’, we got to fight the powers that be.”

“The revolution will not be televised, brother.”

“Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud.”

I pored over these records like they were textbooks. I looked to these singers as elders. This was the era of soul music when Black male singers could be sensual, commanding, political, and vulnerable. Though I’m a child of the ’80s and hadn’t been born when these records first came out, the songs sounded as fresh to my ears as though they’d dropped just yesterday.

Curtis Mayfield, Stevie Wonder, Donny Hathaway, Bill Withers.

Beautiful Black men with beautiful voices, singing powerful, timeless songs about Black survival, Black love, and Black manhood. I imitated their attitudes, their mien, their “soul brother” jive. I prided myself on being hip to this grown folks music. Not until I reached my midteens did I realize these singers had been more to me than entertainers, teachers, or elders; they had been surrogate fathers.

According to 2016 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, more than one-third of Black children in the United States live with unmarried mothers, compared to 6.5% of White children. But while African American children do statistically grow up in single-mother homes at a higher percentage than White children, these numbers are unfairly inflated by focusing on the word “unmarried,” wrote journalist Josh Levs in an article published by Huffington Post the same year as the Census Bureau study. “Many children of divorced parents don’t share a legal address with their fathers but still see their fathers often,” Levs writes. “They’re not fatherless.”

Though I — and many thousands of other Black and Brown boys — had been raised primarily by a single mother, I didn’t consider myself fatherless. My old man was more or less around. I knew where he stayed. I knew what his voice sounded like. And I knew what he looked like. He looked like Marvin Gaye.

Years after I’d reached adulthood and moved away from Michigan, clear across the country to Oregon, I continued listening to old-school soul music, collecting rare vinyl, and occasionally DJing at clubs and bars throughout Portland, spinning the same records I’d first heard in those houses in Ypsilanti, with black velvet paintings on the walls and iron bars on the windows.

During a visit back home in the mid-2000s, my father and I were cruising through Ypsi in his pearl white Cadillac with whitewall tires (dead ass), listening to a Detroit R&B station on the radio, when a Teddy Pendergrass song came on. I started to sing along:

Lookin’ back over my years I guess I’ve shedded some tears Told myself time and time again This time I’m gonna win…

My father turned to look at me. “Boy, what you know about Teddy Pendergrass?”

I smiled. “Man, I love some Teddy.”

He blew a cloud of menthol cigarette smoke at the windshield. “Is that right?”

Thus began our tradition of driving around in his Cadillac, listening either to the radio or to his personal CD collection—some Marvin Gaye, some Luther Vandross, a little Anita—whenever I flew out to Michigan for a visit. He’d be stunned each time I knew the words to a particular song, asking me, “What you know about Stevie?” or, “You don’t know nothin’ about no Bobby Womack.” (On one drive, while listening to his Parliament-Funkadelic CD, my father hipped me to what George Clinton was really talking about when he said he wanted his funk “uncut” and not “stepped on,” which was an especially enlightening conversation.)

Some days we’d cruise into Ann Arbor to go record shopping and we’d play our new finds on the 20-minute drive back into Ypsi, while he’d tell me stories about seeing all these guys in concert in Detroit back in the day. I realized then that these singers who I’d once looked at as surrogates for my father were now, nearly two decades later, the conduit through which he and I could finally connect, communicate, and learn about each other. These songs provided the glue for my old man and me to bond.

My father flew out to visit me in Portland for the first time in the summer of 2016. I had a DJ gig scheduled during his visit and I invited him to the bar where I was spinning, despite the fact that he was getting up there in age, he’d cut back on the drinking, and my start time was way past his usual bedtime. But he came through anyway, sharing a table with a small crew of my friends. He was clearly out of place at this hip new bar, filled with young, mostly White Portlanders, but if he was at all uncomfortable he didn’t show it.

After setting up, I placed a record on the platter and cued up the first song: Donny Hathaway’s “The Ghetto.” My old man whipped his head around as though an artifact from some distant past, some distant world, had just crashed through the roof. He waited a beat, nodded his head, then turned back to my friends, where he regaled them with stories about seeing Donny Hathaway in concert in the ’70s.

He lasted a couple of hours before calling it quits for the night. I still had two hours left of my set, so I called him an Uber to take him back to his hotel. When the car arrived I took a break and walked him outside, explaining that, yes, this man knows where you’re going and no, you don’t need to pay him, I’ve taken care of it.

My old man was getting on in years, there was no mistaking that. He walked slower and had lost his former swagger. He no longer looked like anyone famous — maybe he never did. But he looked like me and I looked like him and that was enough.

We hugged and said good night.

“Good work tonight, Son,” he said, easing into the car. “Enjoy the rest of your set. See you tomorrow.”

“Sounds good, Dad,” I said. “See you tomorrow.”