More than half a century before Aaron McGruder’s first introduced The Boondocks as a comic strip (and later television series) and decades before the biting social commentary found in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury and Berke Breathed’s Bloom County, cartoonist and essayist Oliver W. Harrington set a standard for Black readers, combining his signature wit with incisive social critiques and observations about Black life in America.

Born February 14, 1912, in Westchester county, Ollie Wendell Harrington came of age in the South Bronx, a community that came to define urban malaise in the mid-to-late 20th century. Harrington’s time in public school in the South Bronx helped shape his later career and his political sensibilities. Seemingly anticipating the battlefield that the classroom would become for the fictional Huey and Riley Freeman, and countless school aged Black children, Harrington began drawing caricatures of a White female teacher. As Harrington wrote, the teacher would bring him and another Black male student to the front of the classroom and say, “these two, being Black, belong in the wastebasket.”

With the teacher, Miss McCoy, as his racist muse, Harrington began documenting the everyday pitfalls of his life via cartoons he kept in his notebook. Harrington also recalled a police officer named Dougan, who “had a bad habit” of “ going on a spree every Saturday night and beating the hell out of every Black kid he could find…that was life in the Bronx.” With little recourse, Harrington turned to art and never looked back.

Upon graduating from DeWitt Clinton high school at age 17 in 1929, Harrington left home and set up residence at the famed Harlem YMCA. By the time Harrington landed in Harlem, the financial crisis of 1929 had dampened the excitement that had been brewing, since it had been deemed ground-zero for the New Negro Movement. Nevertheless, Harrington was able to connect with Harlem Renaissance stalwarts like Wallace Thurman, Rudolph Fisher and of course Langston Hughes, who took the young cartoonist under his wing. Among the residents at the Harlem YMCA, where Harrington rented a room for $2 a week, was the future Dr. Charles Drew, who later revolutionized blood plasma research before his untimely death in 1950.

Harrington’s first published pieces in 1932 appeared in Black magazines like the New York State Contender and The National News, which was edited by noted Black satirist (and influential Black conservative) George S. Schuyler. A year later, Harrington began his long-term relationship with The Pittsburgh Courier, which along with The Chicago Defender and New York Amsterdam News (which Harrington also published with) were the premiere Black newspapers in the country.

Harrington’s relationship with the Black Press — a conscious choice when there weren’t legitimate options — highlights the critical role that the Black press has played historically in developing the skills of Black journalists, sales professionals, designers and publicists. Though Harrington could never have hoped to have a cartoon placed in the New York Times, the Black Press offered both the kinds of audiences he desired as well as the opportunity to sharpen his skills.

Harrington’s strip “Boop” (later renamed “Scoop”) began appearing in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1933 and like his earliest work found its inspiration in the lives of Black children. Well before broader society found any significance in what we now refer to as “youth culture,” Harrington used Black children to offer commentary on the realities of everyday life. “Scoop” debuted nearly twenty years before Charles M. Schultz’s Peanuts strip — which McGruder has cited as an inspiration for him. Although there’s no evidence that Schultz was at all familiar with Harrington’s work, Schultz became friends after World War II with Morrie Turner who was the first African American nationally syndicated cartoonist with his strip Wee Pals. We can only wonder what the trajectory of Harrington’s career might have been if he had access to national syndication like Schultz experienced.

Ultimately Harrington found his most influential “voice” in 1935 when his “Dark Laughter” series first ran in The Amsterdam News. It was in the ‘Dark Laughter” strip that Harrington first introduced the character of Bootsie, a Harlem everyman. Scholar M. Thomas Inge, suggests in his book Dark Laughter: The Satiric Art of Oliver W. Harrington, that Harrington attempts to “reconcile the contradictions and absurdities of their daily lives, especially the incongruity between the American Dream and the nation’s failure to fulfill it.”

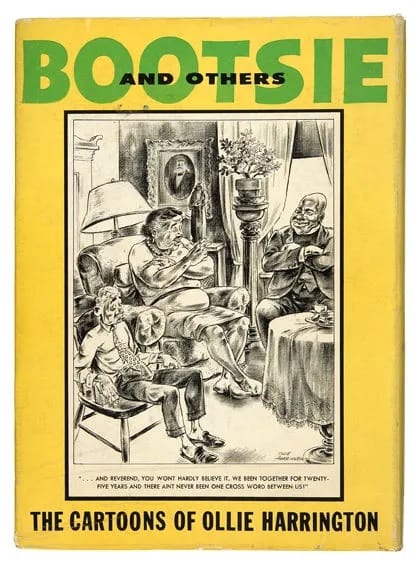

As Harrington recalls, he was “more surprised than anyone when Brother Bootsie became a Harlem household celebrity,” noting in the essay “How Bootsie was Born,” that “to really dig Brother Bootsie, his trials and tribulations, you’d have to see Harlem from the sidewalk.” Every bit as popular as Langston Hughes’s “Jesse B. Semple” character, Hughes later provided the introduction to Harrington’s 1958 collection Bootsie and Others: A Selection of Cartoons.

Always creatively and professionally restless, Harrington moved to Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. ‘s fledgling The People’s Voice in 1942, becoming the newspaper’s art director. One of Harrington’s first projects at The People’s Voice, was a serialization of Richard Wright’s Native Son, which had been published two years earlier. Given the politics of respectability that had dogged even the careers of Black literary celebrities like Hughes, the serialization was pulled because of reader complaints about the profanity that was presented.

Some of the criticism of the Native Son strip also took aim at Harrington, who in another strip commented on the popularity of the Zoot Suits (the hip-hop style of the 1940s), leading readers to complain about his focus on “pimps” and other characters that were thought to demean Black folk. This was also a critique that was aimed at McGruder and many black comedic artists who embrace satire, but in Harrington’s era it also represents his unwillingness to only use his art for simple “uplift” purposes.

As World War II began to rage, Harrington was hired by the Pittsburgh Courier to provide illustrated stories about the experiences of Black soldiers, including the 332nd Fighter Group — the famed Tuskegee Airman. Harrington also created an original strip, “Jive Gray,” which also documented the Black experience in the war. As part of his responsibilities with the paper, Harrington also served as the paper’s war correspondent in North Africa and Europe, allowing him the opportunity to develop a more cosmopolitan worldview.

Covering the war further politicized Harrington. After a spirited debate with US Attorney General Tom Clark in 1946 about several unsolved lynchings of Black men in Georgia, Clark, in response to Harrington’s public militancy, labeled him a communist. Given Harrington’s role as head of public relations at the NAACP (which in the late 1940s was still staffed by legitimate political radicals), he was an easy target for anti-communist sentiment that took over the county in the form of McCarthyism.

Sensing the political shift, Harrington headed to Paris with a generation of Black expatriates including Wright, James Baldwin, Chester Himes, artist Beauford Delaney and Josephine Baker, who had lived in Paris since the late 1930s. In Paris, Harrington became particularly close to Wright and was among the many who believed that Wright’s sudden death in 1960 was the work of CIA operatives. As Harrington wrote seventeen years after the writer’s death, “Wright seemed obsessed with the idea that the FBI and the CIA were running amuck in Paris. He was thoroughly convinced that Blacks were special targets of their cloak and dagger activities.”

After Wright’s death, Harrington only returned to the United States on two occasions, first in 1972 and in 1991, when his work was being exhibited at Wayne State University in Detroit. From aboard Harrington continued to publish his “Bootsie” strips for the Chicago Defender and after that relationship ended, he published regularly for a newspaper in East Germany, where he lived until his death in 1995 at age 83.

Sadly, Oliver Harrington remains a footnote to African American politics and popular culture, though his willingness to sacrifice his career and comfort in the name of using his art to directly address the racist nature of American society created opportunities for others. In February of 2008, eight African American cartoonists staged a “sit-in” — each publishing a common themed strip — to bring attention to the few slots available to Black cartoonists. The artists chose February 10th as the date of the protest because of its proximity to February 14th, which would have been the 96th birthday of Ollie Harrington.

One can only surmise how Harrington would have described the rise of fascism that we are witnessing in the contemporary United States. Would Harrington have utilized Instagram to cut through the clutter of “content,” as one of his progeny Keith Knight has done, so effectively in recent years. Would Harrington still choose to witness the life in America from outside his borders? What remains clear is that Harrington, as noted Art Historian Richard J. Powell has suggested, is an “American Master.”

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.