The former Bad Boy star’s bond with his son is tighter than ever

There was a time between 2000 and 2003 when Amir Junaid Muhadith, born Chauncey Hawkins and known to the world as Loon, was Sean “Diddy” Combs’ most reliable wingman. The native Harlemite, then in his mid-twenties, was the MVP of a post-Biggie-and-Mase Bad Boy Records, injecting “I Need A Girl” and its sequel with a rugged gloss that glued the pair of hits to radio. He released his eponymous debut album on the legendary-but-troubled label in 2003, but the onetime member of the group Harlem World would strike out on his own soon after.

Muhadith was raised by his grandparents in Harlem’s Esplanade Gardens, while his mother grappled with drug addiction. His father wasn’t present either. After a friend was shot outside his building, the youngster was whisked away for a brief stint living in Beverly Hills with his godfather, movie producer George Jackson, before being sent back to New York for fighting.

Having squandered legitimate opportunities, Muhadith immersed himself in the streets, living up to his then-moniker. But his lyrical talent gave him one last lifeline, as he spent countless hours in the studio helping to rebuild a music empire.

After leaving Bad Boy, he dropped two solo albums independently in 2006 (No Friends and Wizard of Harlem) and a joint album with another Bad Boy alum, G-Dep, in 2007. But he never quite reached the same popularity with his music once removed from the house that Combs built. He converted to Islam in 2008 and began to distance himself from the music industry, renaming himself Amir and moving to Egypt in 2010.

Unfortunately, Muhadith’s past in the streets caught up to him in an almost predictable, cinematic fashion. He was arrested in 2011 at a Brussels airport on felony drug charges, based on a loose association with two dealers he had introduced. While he maintained his innocence, two prior felonies on his record gave him little room to negotiate: He faced 25 years to life if he went to trial. With his wife in agreement, he took a plea bargain and was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Like many Black men, he fought to break the cycle of dysfunction when he had his own family. Even while behind bars, he maintained close ties with his wife and children as best he could, even as he was being bounced across time zones.

“My wife visited me one time and she was like, ‘I’m not gonna make no habit of bringing him to no prison.’”

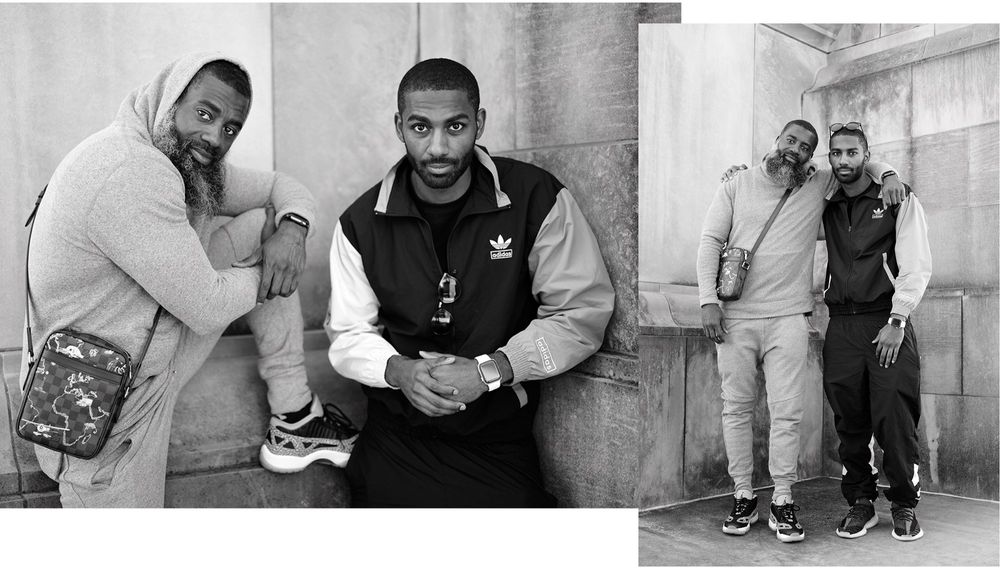

After being granted early release from prison this year due to concerns over Covid-19, Muhadith now lives with his son Bryce, just one of his nine children. The 24-year-old jeweler — named for Groove Theory producer Bryce Wilson, who was classmates with his mom — has been helping his father, now 45, acclimate to life back on the outside, which includes iPhone tutorials and social media refresher courses. Thankfully, Amir has found the ideal wingman in his own offspring. Here, they discuss how Amir’s incarceration affected their relationship and how they’re making up for lost time.

LEVEL: After many years, the two of you live in the same house again. How has this cohabitation been?

Bryce: To be real with you, we’re learning. We definitely have to get used to each other, but I think he’s very considerate. He’s very patient with me and learning that I’m not 15 anymore. You gotta get used to all of that. I feel he’s been giving me the time to get used to having him around again.

Amir: When I first came home, I had to take into consideration that he had to wear a lot of hats in my absence. He had to assume some of the responsibilities of mine, and I know that got to be difficult. At first there was a little friction [because] you got two men in the house now. It’s not a man and his child anymore. I’ve always acknowledged his growth, but when you’re in proximity to it, it’s a whole different experience. And he like to box and I like to box. We’ve trained together since I’ve been home, so that adds another level of respect that’s required when you both possess abilities.

Bryce: He’ll knock me out, though.

I saw the video of you two working out in the gym. Was he in good shape, Bryce?

Bryce: He was in great shape. He’s like an Olympian. That was our first workout.

Amir: He shocked me. We pulled back on releasing videos of the workouts because I think that we could do more, not just for monetary benefit, but [we have] a certain chemistry. You’ve never seen a father and son have compatibility athletically, put together an exercise program, and be a means of mending relationships between fathers and sons.

Have you been catching up on movies he’s missed, like Bad Boys for Life?

Bryce: He does that mostly with my mom and my little sister. They have daddy-daughter days with movies. She has him watch Frozen —

Amir: 100 times.

Bryce: Him and my mom, they’re constantly watching Power and Shameless, catching up on his shows. But me and him are together regardless. I’m cool. I’m happy with how we spend our time.

Take me back to the moment you found out you were going to have Bryce.

Amir: His mother called and told me. It was something that words really can’t explain because I had daughters at the time. The need to be responsible only increased. You already know you want to protect your daughters from everything, but with the son there is a whole different type of cultivation that’s required. Ultimately, as a father, you have to pass something down. It becomes an extension of lineage, which is traced through our fathers, not our mothers. So having a son and knowing you have to pass these things down, it becomes a greater responsibility. It hit me as something I had to be mindful of every single time I was around him. Every single thing that I do, he’s probably going to try to mimic. I didn’t have my father growing up, so I vowed to be a better man to my son.

Part of the reason we’re here is that you’re out of prison after being incarcerated for nine years. Rather than risk serving a life sentence, you took a plea. How did you break that news to your children?

Amir: That’s a funny story. My wife was instrumental in the legal process. Me and her agreed that it would be in the best interest of the family that I take the plea for 10 years. I don’t know how the news got to my son, my wife probably explained it to him. But he wrote me a letter and it was like, “Dad, I understand, but for you to have to hurt somebody else…” He didn’t understand what a plea was — he thought that meant I flipped on somebody. So I got him on the phone and asked him “Do you know what a plea is? I copped out and accepted what was on the table. That’s it.” I can laugh at it now but at the time I was like “What was he thinking?” I know him; when it’s difficult for him to express things, an alternate method is for him to write it. It becomes a gateway to communicate from the heart directly.

Bryce, do you remember that letter?

Bryce: I even remember when I was writing it. I watch a lot of crime movies — you know, in crime movies either they snitch or that’s it.

Amir: I’ve done a lot of things in my life and I’ve been fortunate to beat allegations that were made against me. My wife visited me one time and she was like, “I’m not gonna make no habit of bringing him to no prison.” I had caught a case that I eventually ended up beating, but in the process of that I was jammed up. She gave me the ultimatum that I had already given myself. I’m not gonna do this no more. This ain’t how I’m trying to live and have my son visit me in no jail. That was also a very pivotal moment when I knew I wanted to be in his life and definitely didn’t want to miss a beat.

We’ve been through some trials as a family and we’ve been through some trials as father and son. It’s really built an adhesive — we can always reflect on difficult times and recall what it took to get past those things individually and collectively.

Bryce, how often did you write him while he was inside?

Bryce: How many do you think I wrote you, dad? Like five or six?

Amir: We used to talk a lot.

Bryce: That’s what I was gonna say, he had technology [laughs]. So, I knew how to reach him. When I wrote him, it was really meaningful stuff, but I didn’t have to. When he was put in the hole, that was the only communication we had with him.

How often were you put in solitary?

[Both laugh]

Amir: Quite a few times.

Bryce: It wasn’t that he was in there a lot, they just did it in a way that when he was in there they didn’t let him out. Legally, I don’t think you’re supposed to be in there past 16 days.

Amir: [President] Obama tried to establish something that after three months [you had to be taken out of solitary]. I was doing like three months at a time.

In solitary?

Amir: Yeah. I started off in Belgium with six months. I started this whole thing in a foreign country, which was equivalent to the hole. I was 23 hours locked down, one hour rec[reation]. Two showers a week. One hot meal a day. A phone call every other day. And this is in Belgium, so there was a language barrier. They speaking Dutch and French. That was the very beginning of the whole experience.

Then coming stateside, I did 18 months in maybe four or five different county jails. That was also strenuous because some of them was 20-hour lockdowns, you come out for four hours out the day, not a lot of movement. When I got to the feds, it was the first time I got to stretch my legs. My daughter was like two years old when I got sentenced and three years old when I first got to physically hold her. Bryce was just a teenager. There were definitely times they’d see that letter in the mail [to] know where I’m at.

“What’s crazy is I can unlock his phone with my face. Apple said we look that much alike.”

Bryce: My mom would always know when something wasn’t right, “Have you heard from your father?” She’d be checking the mail everyday.

Today I was driving and Raekwon’s “Have Mercy” played. Beanie Sigel’s verse came on, where he’s talking about being in jail and failing his son on the outside. Did you have those kinds of thoughts while you were inside?

Amir: I think what Beans expressed — our Muslim brother, so As-salamu alaykum to Beans — he expresses the defining commonality that many men that actually are fathers or active parents feel when you have that wedge between you and your child. But I think that the strength that my family had shown during the duration of my incarceration, it strengthens a man in a way that is necessary when you have a strong foundation at home. I’ve seen so much strength, growth, and endurance in my family, even from my daughter. Those moments in the visiting room with her — and him — when they come into the visiting room together. My daughter’s flying past everybody. It was like nobody else was there but us.

Bryce, what’s your earliest memory of your father?

Bryce: This may not be the earliest, but I remember a funny one. We were still living in Harlem before the Bad Boy checks came in. We had a mouse situation and instead of cheese he used to put bacon in the traps. That tripped me out, like why is he giving bacon to a mouse?

Amir: He’s family, yo. He gotta eat what we eat. [Laughs]

Bryce: It was me and my mom in the kitchen. We saw the mouse. My dad was knocked out. Probably just came back from an eight-hour studio session or whatever and he just woke up, threw my mom over one shoulder, threw me over the other shoulder and threw us in the bed and went right back to sleep. Didn’t acknowledge the mouse or anything.

Amir: It wasn’t so much about the upkeep of the home. My wife is a neat freak. But the problem was we had the ground floor — the apartment that the super used. And it was right next to the door to the backyard. So everything living on the ground and in the backyard could make its way into the home. So if she didn’t take care of the house we’d have had way more than one mouse. We thugged it out.

Even reflecting on those memories and seeing what came out of it — I’m proud of him. He ain’t got no felonies, he ain’t got no trouble, he kept his nose clean. He didn’t follow in my footsteps in the slightest. He’s always been his own man. What did I always used to tell you when you were young, Bryce?

Bryce: “Be better than me.”

Amir: He never knew what that meant as a child. As a father, you feel you gotta pass something down. My grandfather who raised me, he used to do the same type of thing. The risks I’m taking out there in the street, your kids don’t know. So I used to always make sure that if things don’t go as planned, [he’d] “be better than me.” I remember when he wrote me that letter…

Bryce: The superhero one?

Amir: He told me he didn’t understand that statement because the way he revered and looked up to me, he didn’t know how he could be better than me. That touched me. Because I always thought he was better than me. When I was 10, I was on 7th Ave. running around hustling, washing cars, packing bags, pumping gas, had a paper route, extorting kids in school. I was busy. So when I see what kind of character he had at my age — he was respectful and didn’t use profane language — [I was proud]. As a father and admirer at the same time, I wanted to remind him to maintain that. Make better choices.

Speaking of choices, Bryce, you’re a jeweler. How did you come to be in that business?

Bryce: I got started when we were in North Carolina. I went to work for this jeweler named Tony. One day, his mom was on her deathbed, and he left me to run the business while he was away. I ended up loving jewelry and from there I went to New York when I was traveling as an electrician. My dad made a call and hooked me up with Jacob The Jeweler’s nephew, Gabriel. I was the only Black kid, Muslim dude, working with these Jewish Russian dudes and being trusted. They don’t just let anybody in. I don’t know how my dad had that kind of relationship where they let me in like that, but they gave me the full run through of their whole empire, and it went much further.

Dad gave you the assist, but you put the ball in the hoop.

Amir: Thing is, he went in there as his own man. Minus the connection, he still seized the opportunity on his own. Because introductions just say it’s an easier vetting process, but it doesn’t take away the effort that has to take place to establish yourself. And I wanted him to know that that was the value of my input. Everything that followed had to do with him. No one is gonna keep you around because they’re friends with your father. He did the work.

Your dad doesn’t seem like the jewelry type anymore. Did you have any other gifts for him upon his release?

Amir: Like you said, I had abstained from all that. And my generation is not into jewelry like that anymore. I didn’t see what he saw, but I had to respect his vision. We used to bump heads on the [jewelry business], so I was like, kid you know you better than I do. I’m not trying to push you away from your dreams and aspirations. You feel like I’m against you but I really just don’t know how to help you. I felt kind of helpless. But the phone call turned out to be more beneficial than the things I would have loved to do for him if I was there. So I give him full credit for chasing something he believed in.

Social media is very different from when you went in and I’m sure Bryce is walking you through it. In what ways have you kind of become the father figure to your dad since he’s been home?

Bryce: When he left, we had Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Instagram didn’t really pop ’til 2014 or 2015, and the whole world changed. He was calling every taxi “Uber” when he got back. That was the first day. When he was setting up his Face ID, I actually got footage low-key recording him, like look at this man in his new world. I know he was bugging out. “Unlock with my face?” This is what he was watching as a kid and we live in that right now. What’s crazy is I can unlock his phone with my face. Apple thinks we look that much alike.

Amir: He was trying to shield me because he knows I take religion very seriously. Some of the stuff that was happening with women, he was like, “Dad, you don’t need to read these messages.” I know what it means to have women inclined to me, but like he said, it’s never been that upfront and direct. Yesterday, we posted a short reel of us on the plane and then somebody sent me a full-blown porn joint. So he was trying to find a way to filter it and connect me to the people I actually know. I’m an old head so I wanna be in the mix a bit. Get in where I fit in.

Read more: Jadakiss and Jae’Won Talk Rap Families, College, and Coffee