"The church is a great archive of Black music.” — Nikki Giovanni

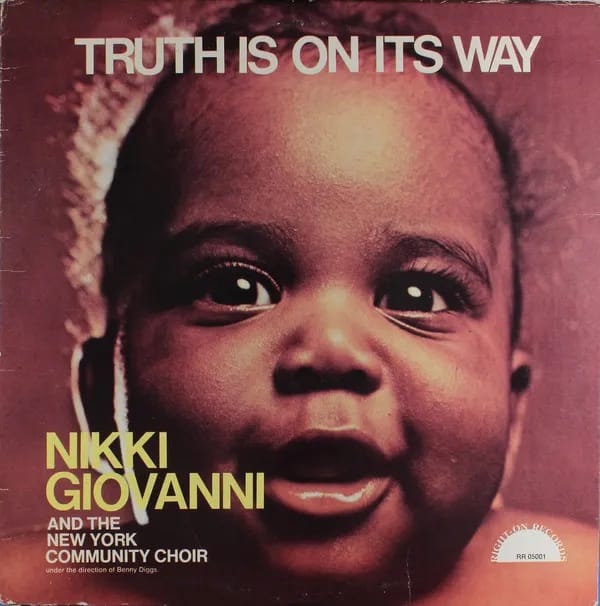

Amiri Baraka once wrote that Black music, “to retain its freshness, its originality, its specific expression of its own history and contemporary reality in each generation creates a ‘new music’.” This was yet another articulation of what Baraka once called the “changing same” — the thing that links Black expressive culture to a commitment to innovation, while remaining wedded to the traditions and archives that birthed it. No one understood that better than Nikki Giovanni, when she went into the studio to record Truth is On Its Way in 1971.

Giovanni, an activist, poet, and iconclast, passed away on Monday in Blackburg, Va from lung cancer complications. She was 81.

I was five years old when my mother walked into the house with a copy of Truth is On the Way. I’ve listened to the recording hundreds of times since then; indeed Giovanni’s cadences are embedded in the rhythms of my own writing. At the time I didn’t fully understand the genius of her vision — she was blatantly trying to bring the profane in conversation with the sacred, two decades before Kirk Franklin and later Kanye West would bring ghetto theodicy to the top of the pop charts.

Giovanni was one of the most visible and provocative poets of the Black Arts Movement — Baraka, Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti), Sonia Sanchez and the late Henry Dumas among them. The Black Arts Movement was premised, in part, on the idea of an art that was “for the people,” thus many of the movement’s artists sought to make an explicit connection to folk up on the boulevard. As Howard Rambsy writes in his book The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry, figures like poet and publisher Dudley Randall and Negro Digest editor Hoyt Fuller curated literary magazines and anthologies that were “collectively and largely responsible for providing widespread exposure to both the writings and the activities of black poets during the 1960s and 1970s.”

Released in 1971 on the independent Right-On label founded by Carl Proctor, Truth is on Its Way featured poetry drawn largely from Giovanni’s first three collections: the self-published Black Feeling, Black Talk (1968) as well as Black Judgement (1968) and Re: Creation (1970), both published by the aforementioned Dudley Randall’s Broadside Press. As Virginia Fowler writes in the introduction to Conversations with Nikki Giovanni, the poet “‘took her poetry to the people’ appearing regularly on radio and television talk programs and speaking in churches, in coffeehouses and clubs, in schools, on college campuses — anywhere she was invited.” But Truth is On Its Way was born out of more than wanting to capitalize on her poetry and reach a larger audience — Black Judgement sold more than 10,000 copies in its first year — but also an attempt to bridge an emerging generational gap within the Black community, particularly with regards to liberation politics.

To that end, Giovanni eschewed the use of West African drumming as accompaniment to her poetry — a style made popular by The Last Poets — and instead chose to record with a Gospel choir. The choice of the New York Community Choir was inspiring. Founded in 1971 under the direction of Benny Diggs, the collective coalesced around the talents of Isaac Douglas, Arthur Freeman, and Wilbur Johnson. Often billed as Isaac Douglass and the New York Community Choir, the group recorded a half-dozen albums in the 1970s, including A Little Higher (1972), which featured songs from a then relatively unknown Timothy Wright and the classic New York dance track “Express Yourself.” They are most remembered though for the two albums in which they backed Nikki Giovanni, including Like a Ripple on a Pond (1973).

“I wanted people to take not just my poetry, but something I thought was a valid comment on my poetry which was gospel music,” Giovanni told M. Cordell Thompson in Jet Magazine (May 1972). Giovanni adds, “Let’s say that old people have bad eyes, or, we don’t like to talk about it, but a lot of people, first of all, cannot read. These people can put the album on and listen to it and really understand its message.”

Truth is On Its Way opens with the classic “Peace Be Still” with Isaac Douglas on lead. Originally recorded by Reverend James Cleveland in 1963, the song transformed Mary Baker’s 1874 composition “Master, the Tempest is Raging” into a Gospel standard. That was the perfect allegory perhaps for a tumultuous period in which Black communities that were literally under siege by the state and other extralegal forces. Giovanni sought to make such a connection explicit as midway through the song she breaks into her poem “Great Pax Whitey” taking aim at American hegemony: “and America was born/where war became peace and genocide patriotism/and honor is a happy slave/cause all God’s ‘chillen’ need rhythm.”

Giovanni and the New York Community also go to Rev. Cleveland on “All I Gotta Do/I Stood on the Banks of Jordan”, which features the high-pitched vocals of the late Arthur Freeman alongside Giovanni’s stark rebuke of the gender politics of the Black liberation movement. “all i know/is sitting and waiting / waiting and sitting / cause i’m a woman / all i know / is sitting and waiting / cause i gotta wait / wait for it to find / me.”

On the track “Second Rapp Poem/This Little Light of Mine” Giovanni pays tribute to the “real talk” activism of H. Rap Brown (the now incarcerated Jamil Al-Amin): “they ain’t never gonna get Rapp/he’s a note, turned himself into a million songs/Listen to Aretha call his name.”

And it was Ms. Franklin who inspired one of the album’s most poignant moments, via Giovanni’s “Poem for Aretha.” As the lead vocalist Wilbur Johnson mournfully sings “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” Giovanni gives praise to the woman who was, arguably, the most important and popular Black women artist ever. Written at the height of Franklin’s fame, Giovanni places Franklin within the context of great Black music (“pushed every Black singer into Blackness”) and the tragic lives of her artistic foremothers (“Aretha doesn’t have to re-live Billie Holiday’s life/doesn’t have to re-live Dinah Washington’s death”). The gravity of Giovanni’s poem is so clear, as we witnessed the slow demise and death of Whitney Houston.

Though Gil-Scott Heron and The Last Poets are often credited as the “god-fathers” of Hip-Hop, Giovanni, who recorded five albums in the 1970s, doesn’t get nearly enough credit for her contributions. With a track like “Ego Tripping” — the only track on Truth is On Its Way not backed by Gospel music (though no less spiritual) — one hears the impact that Giovanni had on the poetic sensibilities of the Hip-hop generation. The song is the very essence of an old-school rap boast (“the filings from my finger nails are semi-precious jewels”), released two-years before the much celebrated Hustlers Convention.

Twenty years after “Ego Tripping” was first published in Re: creation, the poem was featured in an episode of A Different World, performed by the women in the cast, and a decade after that the recorded version of the poem was remixed by Blackalicious on their disc Nia (1999). Indeed Hip-Hop’s poet laureate Rakim Allah might have been thinking about Giovanni’s line “I turned myself into myself and was Jesus” when he wrote the lyric “My name is Rakim Allah / And R & A stands for ‘Ra’ / Switch it around / But still comes out ‘R’” on his classic “My Melody.”

In the liner notes to Truth is On Its Way, Ellis Haizlip, host and producer of the legendary Soul!, wrote of Giovanni, “the possibility is that she can bring about a new reality that will release us — the American Black — from some very crippling concepts of the American mythology.” After such a long and vital career as a poet, activist, teacher and commentator, no one would dispute Haizlip’s claim. Truth is On Its Way is just a reminder of how evident Giovanni’s vision and genius was, from the very beginning.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.