Back in early March, Rynell “Showbiz” Williams was on the phone with his friend Yancey Richardson, a producer who also does promotion work for Atlantic Records. Williams, 40, is a radio DJ in Monterey County on California’s Central Coast — but like Richardson, he grew up farther north in Oakland, and the two began reminiscing about Soul Beat, the cable TV network that was only available in their hometown and a few East Bay suburbs. From 1978 to 2003, the Black-owned network on channel 37 catered unapologetically to its city’s African American population, and provided the first television exposure for many local R&B and rap artists.

It could also be, in the parlance of its time, hella janky.

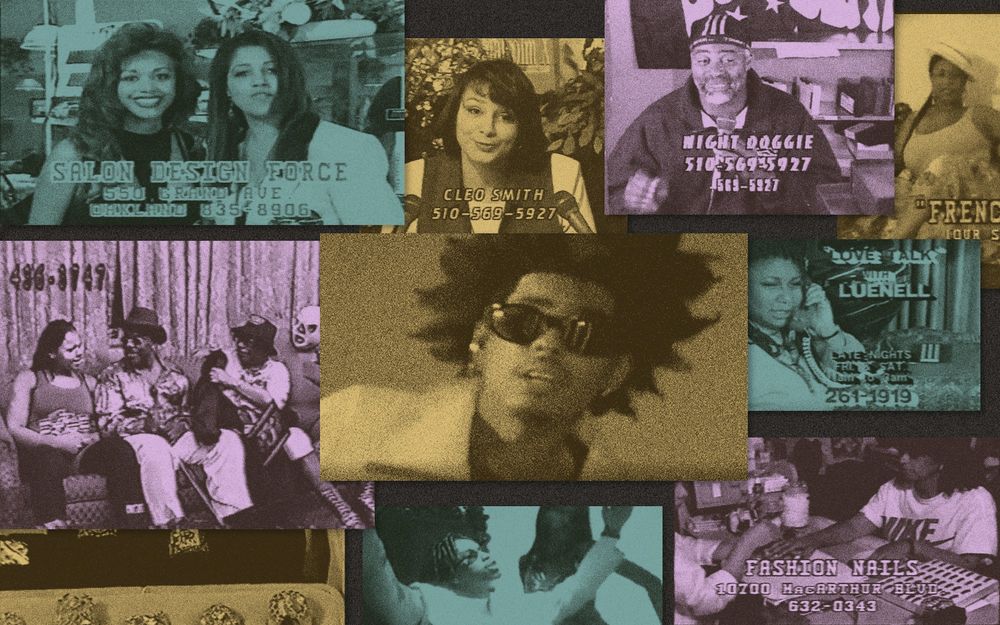

No plush corporate offices for Soul Beat; the network filmed its shows in rented apartments, personal homes, and a studio in Oakland’s notorious Eastmont Mall. Its VJs would broadcast live without the protection of a delay, which meant viewers could watch them get prank-called and otherwise harassed by local teenagers. Most of the commercials were for mom-and-pop businesses where the proprietors delivered unpolished pitches for their seafood restaurant or private hot tub rentals. When the rare ad showcased the franchise of a national chain like McDonald’s, it might feature a Soul Beat personality like Night Doggie, a gray-haired dude in a beanie who was missing his front teeth and would deliver his lines in raspy, sometimes incomprehensible barks. Even the newest music videos Soul Beat showed looked worn down and murky. It wasn’t just lo-fi — it was defiantly homegrown, sticking to its sensibility even after BET and MTV came along.

But when Williams hit the internet to further satisfy his Soul Beat nostalgia, there wasn’t much there. He found some clips of Soul Beat broadcasts and commercials on YouTube, and a few obituaries for station founder Charles “Chuck” Johnson, but nothing that captured Soul Beat’s unique presence or its importance. Williams set out to change that. On March 6, he started his own Instagram tribute account, posting whatever digital remnants of Soul Beat he could find, and also sharing music videos from mostly forgotten Bay Area acts that the station used to play, like Oaktown’s 357 and Black Dynasty.

“If you see your video on Soul Beat and you see Run-DMC at the same time, it makes you feel like you can compete with those people” — Raphael Saadiq

As stay-at-home orders rolled across the U.S. due to the spread of Covid-19, Williams found he had a lot more free time to dedicate to his account — and so did its followers, some of whom were former Soul Beat employees. They dug through their own archives to unearth old VHS recordings of the station, which they digitized and sent his way.

Soul Beat has been off the air for nearly 20 years, but its story is still relevant. In recent years, an entire microgenre of films has emerged that chronicle how gentrification has changed the face and character of the Bay Area. Blindspotting, Sorry to Bother You, and The Last Black Man in San Francisco make their cases about the societal forces that have closed local businesses and pushed much of the region’s African American population farther inland or completely out of state. While these movies (along with novels like Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue and a cascade of articles) lament an identity that’s being lost, Williams’ Soul Beat account is able to do more — to chronicle places and people that are already gone. “I really do consider it a history lesson,” he says, “not only of musical Bay Area culture, but a time capsule of the Bay Area. Especially Oakland.”

Chuck Johnson was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1938, but grew up in Kansas City. He worked at a radio station there as a teenager, and after a stint in the Air Force became a disc jockey himself, heading west and getting a job at an FM station in Los Angeles. In the early 1970s, he bought the San Diego cable station CATV, where he played country music performances and showed old westerns. As Johnson told the East Bay Express in 1997, his personal catchphrase for CATV was, “Blacks behind the camera, Whites in front of the camera.” He became a broader participant in Southern California’s Black entertainment industry throughout the decade, including doing promotion work on one of Rudy Ray Moore’s Dolemite movies and directing the Isaac Hayes concert film The Black Moses of Soul. In 1978, he decided Oakland was the best place for his concept of an all-Black cable network — and Soul Beat, one of the first, was soon on the air. (Detroit’s WGPR operated from 1975 to 1995 as the first Black-owned television station, and BET would begin in 1980 as a two-hour-long block of programming, becoming its own standalone station in 1983.)

“[Soul Beat is] right in lockstep with the Too Shorts, E-40s, or the Hieroglyphics of the world, and in that way, even [MC] Hammer — just seeing that you could do it yourself and create a movement.” — Tajai of Souls of Mischief

With Soul Beat, Johnson followed a similar approach to the one he had developed for CATV, but adjusted it for a different audience: taping performances and interviews with the day’s major R&B and funk acts, and screening blaxploitation films. As music videos became an important medium for record labels — and as those from Black artists were largely ignored by MTV — Soul Beat increasingly turned to them to fill up its broadcast hours.

“Soul Beat was everything to us,” says singer and producer Raphael Saadiq, who used to tune into the station with his brother Dwayne Wiggins before they started their band Tony Toni Toné. “We watched it every day.”

Saadiq still remembers the footage that Soul Beat would show of Michael Jackson performing to backing tracks at New Age, a club in Downtown Oakland, during the Off the Wall era. In 1988, the station began to play Tony Toni Toné’s Sinbad-featuring clip for “Little Walter,” their first single. “If you see your video on Soul Beat and you see Run-DMC at the same time, it makes you feel like you can compete with those people,” he says.

For generations, Bay Area hip-hop has been driven by a tireless, self-propelled hustle. The roots of this approach date back to the mid-1980s, when, without support from the radio and record labels, the region’s enterprising first rappers sold their self-released records from the trunks of their cars, or recorded custom songs for neighborhood drug dealers. Even if Soul Beat didn’t always prioritize them, the Bay’s rappers saw a kindred approach in the channel’s scrappy operation. “It helped us understand supporting locally, and as I’ve gotten older, understand doing things independently,” says Tajai of the rap group Souls of Mischief. “[Soul Beat is] right in lockstep with the Too Shorts, E-40s, or the Hieroglyphics of the world, and in that way, even [MC] Hammer — just seeing that you could do it yourself and create a movement.”

Soul Beat continued to show live performances from touring and hometown acts, putting a camera on the balcony of venues like Sweet Jimmie’s, which catered to a more grown-folks crowd. “People like Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland or B.B. King would come through and do shows there, so you could sit home and watch your parents at the club that night,” says Luenell, the East Bay-raised comedian whose own career got an early boost from popping up in Soul Beat commercials and appearing as a host on the channel.

In its more civic-minded programming, the network ran shows like Political Beat, Morning Beat, Real Estate Beat, Health Beat, and Garden Beat. On another show, older women would sell products directly to viewers like it was the Home Shopping Network. Sometimes Soul Beat would just play footage Johnson shot while on the vacation in the Caribbean. “The only thing we didn’t have was auto repair,” says James C. Earl-Rockefeller, who worked behind the scenes at Soul Beat before becoming one of its on-air personalities.

The city’s Black residents saw the station as a place they could turn to when other outlets weren’t available to them. “If you had a lost child, you could go to KPIX [the San Francisco-based CBS station] and say, ‘Hey, my child is lost.’ They’d be like, ‘Yeah, take a number,’” says Luenell. “If you came to Soul Beat, we would let you on [the air]. You could show a picture of your kid and within like 15 minutes somebody would probably call and say, ‘Oh yeah, she’s ‘round the corner at my homeboy’s house.’”

The station showed sermons from Yusuf Bey, a former member of the Nation of Islam and a proponent of Black nationalism. It also had a news program hosted by journalist Chauncey Bailey. These two men’s histories would later intersect in a far more upsetting way in 2007, when one of Bey’s sons, Yusuf Bey IV, ordered the killing of Bailey because he was working on a story about the financial mismanagement of the Your Black Muslim Bakery. Four years earlier, the elder Bey died from cancer while awaiting trial on multiple counts of rape and having sex with underage girls.

Dashka Slater, a reporter who wrote an East Bay Express cover story on Soul Beat, grew up in Massachusetts, but after graduating from UC Berkeley she moved to Oakland and began covering the city for the free weekly. She regularly tuned in to Soul Beat to generate story ideas. “It was an opportunity to listen in on conversations I might not have heard otherwise and to hear this segment of Oakland that wasn’t always well represented at City Hall,” Slater says. “I was learning about the diversity of Black opinion and Black politics in this incredibly diverse city.”

During her time reporting the piece on Soul Beat, Slater spent significant time with Johnson, including a visit to his Oakland Hills home where there was a television in every room — each one always tuned in to his station. She got to see firsthand the obsessive fashion in which he ran the network. “He was somebody who invented himself, invented a job, and a business that hadn’t been open to him any other way,” says Slater. “People like that can be a tough row to hoe when you work for them. The exact same qualities that make you good at your job also make you really difficult to work for.”

Though Luenell speaks fondly of Johnson, she is less diplomatic than Slater when describing his leadership style. “He was a dictator, for sure,” she says.

Earl-Rockefeller remembers one night when he, Luenell, and Lil Bo P (another one of the station’s hosts) were supposed to perform at a standup comedy show that would be broadcast on Soul Beat. None of them wanted to go on first because the club was still empty. The next day, they learned that they’d all been laid off. To get his job back, Earl-Rockefeller went in to meet with Johnson. “I’m sitting there feeling myself, telling Chuck how important I am to Soul Beat,” he says. “And Chuck was like, ‘Hold on man, you’re not Soul Beat. I’m Soul Beat. If I took you off the air and put somebody else on there, they’ll be watching them instead of you.’ And in that moment I got super humble. He checked me, and I still remember that incident. I appreciated it because I was like, ‘Damn, he’s actually right.’” His lessons heard, Johnson eventually hired them all back.

Another Soul Beat alum, Renee Moncada-McElroy, was from across the Bay Bridge in San Francisco. She moved to Oakland in the early 1990s and began watching Soul Beat; even though she had grown up less than 20 miles away, she had never heard of the regional phenomenon. While studying broadcasting at nearby Cal State Hayward, Moncada-McElroy got an internship at Soul Beat to fulfill a graduation requirement — but hoped she could use her newfound education to improve basic production-quality issues like lighting and camera placement. “Once I got in there,” she says, “I realized that wasn’t what Chuck was interested in at all. His bottom line was always community and ownership.” (After a stint at Soul Beat, she went on to make shows for stations like the Discovery Channel and TLC, and produced the Fuse series Big Freedia: Queen of Bounce; she’s currently putting together a docuseries about Soul Beat.)

Some believe that the story of Soul Beat is one of wasted potential, that if Johnson had wanted to, and was willing to give up some of his control, he could have brought in investors to take Soul Beat to the level that Robert L. Johnson did with BET.

The most derided — though beloved — aspect of Soul Beat’s aesthetic had to be its commercials. They were usually filmed and edited by Johnson or one of the station’s employees, who sometimes wouldn’t bother to record another take even if a line was flubbed (or if a restaurant’s busboy accidentally walked into the frame and then awkwardly backed out). But this perceived lack of professionalism was another deliberate choice for Johnson. “He said people love that they’d see their aunt or their cousin in [the commercials],” says Slater. “They don’t leave the room to go get a snack during the commercials, they stay and watch because it’s somebody they know.”

Scrolling through Williams’ Soul Beat account on Instagram today, the commercials are particularly endearing, especially since so many of the places have long gone out of business. “These weren’t people with tons of money to spend on advertising, but this was their outlet to do so,” says Williams. “I remember laughing at those commercials in terms of their quality, but now I realize this is what was available to them, and how crucial it was for both for the channel and those businesses.”

As the 1990s rolled on, hip-hop became the dominant sound of Black music. Like many Black boomers, Johnson had issues with what he felt the culture was glorifying. “Chuck had a large church following, he was very community- and family-oriented,” says Moncada-McElroy. “The language, the weed-smoking, just the whole street aspect of rap music wasn’t something that he liked. But he knew that this was a generation coming and there were some really great artists.”

The HipHopSlam YouTube account recently posted a 1993 video of Johnson interviewing Eazy-E, but for the most part, he left the rap world coverage to others. Soul Beat had a young employee — this one also named Chuck Johnson, though no relation — who was operating cameras and doing advertising sales. He was a huge hip-hop head, so he got a show to spotlight the sound. During the two years that the matter-of-factly named The Rap Show With Chuck ran, it featured interviews with acts including Jay-Z, the Conscious Daughters, and Goodie Mob.

The younger Chuck Johnson would study the playlists of Yo! MTV Raps and Rap City, and when he’d come into the station he’d sometimes find videos for songs that the other channels hadn’t started playing. His boss wouldn’t even know what he was sitting on. “I would walk in his office like, ‘Yo, did you know that we had his video?’ And he’s like, ‘Heh?’” remembers Johnson. “And I’m like, ‘Chuck, get a fucking clue. This is the hottest song on KMEL [the region’s biggest hip-hop station] for us youngsters and there’s a video for it and it hasn’t been on the air yet. You don’t know what type of props I’m about get for the next week ’cause I’m doing this. Like, I might get a new girlfriend ’cause of this.’”

In 2004, Johnson died from cancer at the age of 66. By that time, Soul Beat had already stopped broadcasting on cable and moved online — a decision born out of necessity. In 1997, the television station was shut down because Johnson owed the Internal Revenue Service $37,000. While Soul Beat got back on the air after raising the needed funds via telethon, the station would periodically go dark; ultimately, in November 2003, Soul Beat was pulled from the cable provider Comcast due to hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid bills.

Without Johnson, Soul Beat would no longer go on. (Five years ago, Soul Beat.TV accounts unaffiliated with Johnson’s family launched on YouTube and Vimeo, sporadically posting new videos of Bay Area performances and getting minimal views.) Still, the network’s demise felt unexpected for many. “I assumed it was going to go on forever, I really did,” says journalist Slater. “But you know, I couldn’t imagine a lot of the changes that came to Oakland. ’90s Oakland really did feel like it was going to be Oakland forever because there was this sense of frustration about the way things didn’t change — the good parts, the bad parts, like none of it was going to change.”

Johnson had a distinct vision of who Soul Beat was for, but over time that potential viewership became increasingly smaller and marginalized — a function of multiple transformative factors, from the tech boom to a shortage of affordable housing in the Bay Area to the internet. Some believe that the story of Soul Beat is one of wasted potential, that if Johnson had wanted to, and was willing to give up some of his control, he could have brought in investors the way Robert L. Johnson had with BET — a move that ultimately paid off when he sold the network to Viacom in 2000 for $2.3 billion in stock. But for better or worse, that type of financial windfall never really seemed to be his goal. “Rob and Chuck kind of started off on the same level, and Chuck always used to say, ‘I didn’t sell out,’” Moncada-McElroy remembers.

Others are more forgiving of Chuck Johnson’s approach. They believe he was protecting his creation and the people it was for, not holding on to it so tight that it eventually crumbled. “We create these things within our community for our community — support it, build it up to the point where those outside notice and they want to purchase it,” says Tajai. “Then, once they purchase it, they use it like a hammer to crush our community.”

But those arguments are all theoretical now. Like Oakland fixtures Sweet Jimmie’s, Art’s Crab Shak, the MacArthur-Broadway Shopping Center, Brass & Glass furniture, the Festival at the Lake celebration, and The Jacka, Soul Beat is gone. When you get lost in the feed of Williams’ Instagram account, ideas about what could or should have been briefly disappear. What’s left is a depiction of what was.