In 2020, what we mean by the term “streetwear” is virtually unrecognizable from its origin. At its genesis, the confluence of skate culture and hip-hop created a means for people to express themselves aesthetically outside the conventions — and prices — of mainstream style. This aspect fostered the community Virgil Abloh lamented in comments he made during the first weekend of demonstrations following George Floyd’s death. “Streetwear is a community,” he said. “It’s groups of friends that have a common bond. We hang out on street corners, fight with each other, fight for each other.”

Left unsaid in this statement is that as the price of these garments have risen, the groups of friends who could afford to congregate around streetwear changed. This, coupled with the internet’s ability to push the same goods onto everyone in the world, has created a bottleneck effect. If things are affordable, they’ll be restricted by availability (like Supreme). If they’re readily available, they’ll be prohibitively expensive. The end result is a consumer stuck on the outside looking in. In a world where Off-White hits the same price range as Gucci, why would consumers view them any differently?

If Abloh’s connection to the culture is his superpower, the wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations — and his response to it — has been his kryptonite.

These factors became evident when a loud but small group of Los Angeles rioters looted Sean Wotherspoon’s Round Two store and Don C’s RSVP Gallery space — moves that earned the disgust of Abloh. “When you walk past Wotherspoon in the future, please have the dignity to not look him in the eye, hang your head in shame,” the 39-year-old designer said of the vandals. Meanwhile, Don C posted pictures of the damage done to RSVP Gallery, with his Instagram stories oscillating between wondering how he’d contributed to consumerism and threatening third-degree manslaughter upon protestors “as soon as the glass is broken tonight.”

The common thread between the responses is a prioritization of property above life, and a deep disconnect from the sociopolitical issues at hand. Both designers failed to express that the vandalism paled in comparison to the police brutality that was being protested. Abloh’s comments also had the terrible optics of shaming Black protestors due to damage done to a White store owner’s property. It was the worst kind of color blindness, which suggested that perhaps his connection to the culture is primarily financial.

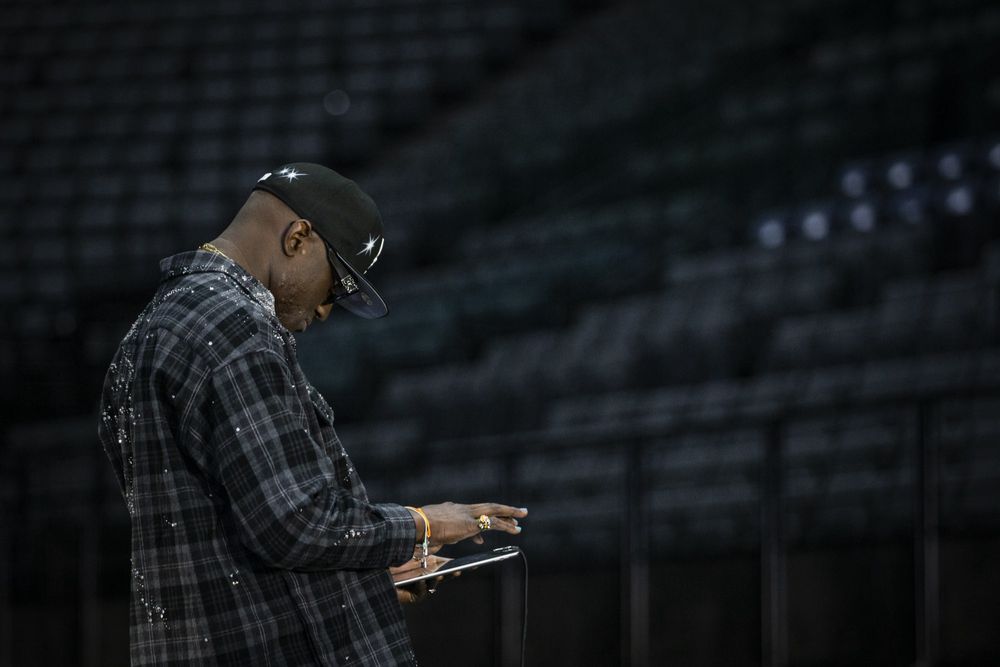

To be clear, it’s “the culture” that got Abloh to where he is today. He’s got an enviable ability to make kids queue to purchase his goods. In a 2019 New York Times feature, Nike’s senior design director Jarrett Reynolds said that Abloh’s “superpower is his connection to culture.” Davide De Giglio, co-founder of New Guards Group (the parent group of Off-White), pointed out that, “Virgil is there with the kids when there’s a store opening somewhere in the world. He’s signing sneakers, talking to the kids, taking pictures. This is very important.”

If Abloh’s connection to the culture is his superpower, the wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations — and his response to it — has been his kryptonite. Even his apology, which claimed that the protests were more important than damaged property, inadvertently laid bare Abloh’s previous avoidance of the topic of race.

“I’m a Black man,” he wrote in a lengthy social media post, seeking to align himself with the plight BLM supporters were protesting. “A dark Black man. Like dark-dark.” He continued to point out that he created his “Community Service” project specifically to benefit young Black designers — a far cry from its initial February unveiling, in which he only spoke of “a life goal to creatively update the idea of charity.” After being averse to discussing race, this was a convenient time for him to speak about it so explicitly.

It didn’t help that Abloh had previously posted a screenshot of a relatively meager $50 donation to Miami-based organization Fempower, which is assisting with bailouts for arrested protesters. His apology clarified that the aforementioned contribution was part of a matching challenge with friends, and that he’d actually donated $20,500 to “bail funds and other causes related to this movement.” But the damage had already been done — the screenshotted donation quickly became a punchline on social media, and spurred a conversation highlighting the exorbitant prices of “streetwear” products. Who is the target audience here: $275 for a belt? $400 for Don C’s Milwaukee Bucks shorts?

With the highest unemployment rate since records began, minimal governmental assistance through a pandemic, and rage over police brutality that has somehow managed to surge even in response to the demonstrations, folks don’t give a fuck about the capitalist ventures of large businesses, Black-owned or not. Abloh has long been aware of this gap between inspiration and consumer. In a 2016 interview, he responded to claims that his prices are too expensive for an audience that serves as his muse by saying, “Of course my brand is inspired by the youth. I wouldn’t say it’s directly made for the youth.”

Ironically, it’s the same youth from which Abloh gleans inspiration that is now shunning him. For a designer who trades on cool, looking like a monied outsider is as close to a death sentence as you can get. The impulse to lean into his Blackness explicitly in his apology after years of leaving it unmentioned underscores another widely known truth: Black folks are the barometer of cool. And regardless of affordability, Abloh needs that audience’s support to continue hawking his Off-White pieces.

On a larger scale, these debacles laid bare the streetwear sphere as it is today: a world where a select few enjoy the trappings of success while relying on those of lower economic statuses to prop them up. Folks like Don C and Virgil Abloh may use the phrase “the culture” when it benefits them — but when push came to shove, they put themselves first.