When the game against the Memphis Grizzlies ended, Clippers forward Montrezl Harrell made his way into the catacombs tucked beneath the Staples Center stands. He showered, quietly dressed, and steeled himself for the postgame press scrum next to his locker. The silence was uncharacteristic for Harrell, whose penchant for bombast had carried his team to a number of hard-earned wins in what was supposed to be a rebuilding year. But grief is a thief, and that night it had sapped his energy dry.

As the reporters began to pepper him with questions, Harrell’s mouth drew taut, his stare lasered through their heads. A journalist asked him about the biggest story of that day, far bigger than a regular-season game: A man had been shot and killed earlier, just a few miles southwest of Staples Center. “Honestly, man, any type of death can take a toll on anybody,” Harrell said, his gaze downward. “Any form of taking someone’s life is wrong, man.” He kept his answer detached, professional. He knew the questions that night wouldn’t be about his 20 points off the bench, his symphonic pick-and-roll with teammate Lou Williams, or any of the other things that would normally prompt platitudes about “staying aggressive” or “taking every game one at a time.” Not that night.

Instead, everyone was going to be talking about the pall settling over the arena, about the loss of one of L.A.’s most well-respected statesmen, about what it means to go from running in them streets to running them streets. Everyone was going to talk about the name that tonight was etched on the back of Montrezl Harrell’s familiar number five jersey, hanging behind him at his locker: Hussle.

Their stories, and the ways they told those stories, wailed hip-hop, from the volume at which they shouted out their friendship to the ways players channeled their mourning. Players wore their sorrow like wounds, wrote lament on their bodies and through their play, granting themselves and their grieving audience both solace and catharsis.

The sudden, tragic murder of Nipsey Hussle one year ago today forced the parallel universes of rap, sports, media, and the quotidian to collapse upon one another. Virtually every corner of the entertainment industry simultaneously mourned and celebrated the valences of his life: his final album, Victory Lap; the love he showed his partner, Lauren London; his block-based business acumen. Nip’s message of Black empowerment and the even-keeled groove with which he delivered it struck a chord with street cats and suits alike. But perhaps the most striking display of mourning, that day and in the immediate aftermath, came from his brothers in public life in the NBA.

The initial reaction from all corners of the sports world was immediate. When it seemed like he might pull through, players sent up prayers in hopes that a miracle could bring back L.A.’s patron saint. As the reality of his death set in, dedications swelled. A deluge of social media posts streamed in from the game’s elite players, giving us brief glimpses into the breadth of life that Nipsey was able to pack into 33 short years. Both NBA teams that call the Staples Center home honored him with tributes.

On the court, players memorialized the man and celebrated the cultural symbolism they shared. Their stories, and the ways they told those stories, wailed hip-hop, from the volume at which they shouted out their friendship to the ways players channeled their mourning. Players wore their sorrow like wounds, wrote lament on their bodies and through their play, granting themselves and their grieving audience both solace and catharsis.

Make no mistake: This could only happen in basketball.

What separates the NBA from the NFL or MLB is the same thing that has made it so intimately proximal to hip-hop. “Rap or go to the league” isn’t just an album, it’s a mantra — an unfortunate statement on the lack of opportunities for Black and Brown kids in hoods across the country. Those who found success were bred in this same crucible, survived very similar streets. Deep into their careers, the relationship between practitioners of both art forms are open to the same forces working against them. Rappers, like NBA players, navigate the tangle of extraordinary talent, business, race, and living a very public life. Both are microscrutinized for talent and aesthetics alike, scrutiny that directly affects their earning potential.

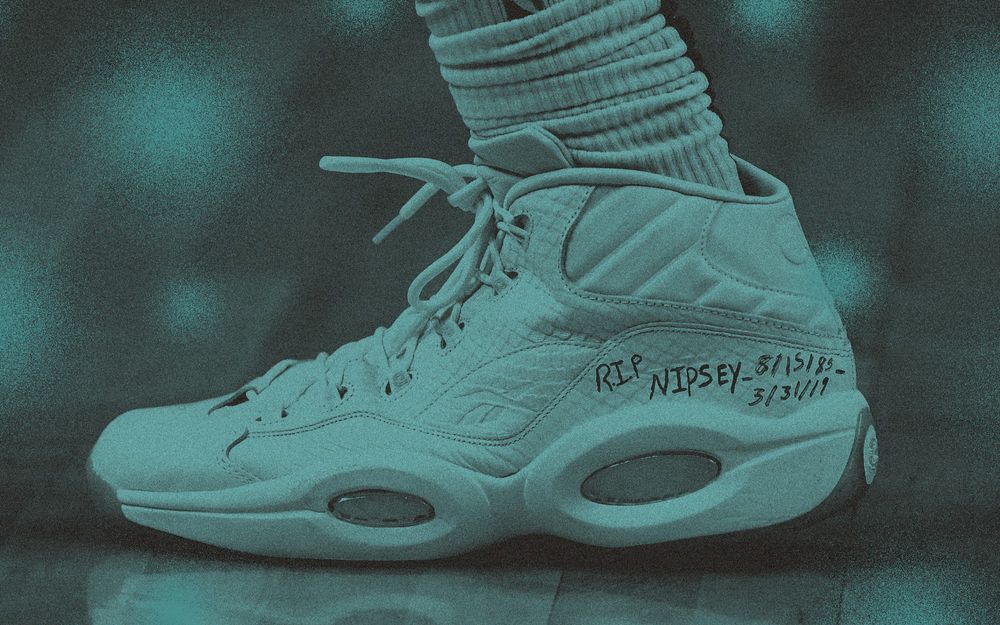

It’s little wonder, then, that the NBA became a site for men to render themselves vulnerable — cracked open by a senseless murder that, for many of the league’s top stars, reminded them too much of home. The face of the league, LeBron James, bore Nip’s visage in the pregame runway. Montrezl Harrell not only paid homage on his shoes and a custom jersey but also asked the Clippers organization for a video tribute before the game, to which they quickly agreed. Dwyane Wade and Kawhi Leonard, legends present and future, rocked love on their soles. (That famously stoic Leonard had signed with New Balance just months before, allowing him to speak volumes by Sharpie-ing the letters “IP” after his sneakers’ signature “N,” felt like providence.) Angelenos James Harden, DeMar DeRozan, and Danny Green all inscribed his name on their sneakers. Harrell even commissioned a pair of Jordan 10s, customized with mural-style art of Nip and his lyrics. To commemorate loved ones on one’s game shoes is common practice in the NBA. Yet, “loved ones” typically means family or members of the NBA fraternity; to mourn a fallen soldier from another walk of life entirely is something far rarer.

Nor did it stop there. If Nipsey’s presence infiltrated the court through clothing and sneakers, over time players found ever more personal means of expression. Jordan Clarkson and J.R. Smith etched Nipsey’s face onto their skin. Pelicans guard Lonzo Ball added his countenance to a tattoo sleeve that also featured Malcom X, MLK, and Rosa Parks. While that pantheon may seem ill-considered, Nipsey’s message did share some of the workmanlike sensibilities of those civil rights leaders. The street represented the spiritual center of the nation; if Black people could control their own street, they could then enact change across the nation. The Marathon store signified that mission for men — though seemingly, and harmfully, only for straight men — to activate change on a street level.

There was one other way as well—one way adoration was expressed beyond press conferences and tweets, beyond ephemeral outfits and permanent ink. The kinetic, balletic tongue that every one of the Association’s 450 active players speaks: The game, baby. It’s always been the game.

And it was in that language that one of the league’s most ferocious talents performed perhaps the greatest tribute an athlete could make.

Two nights after Nipsey Hussle’s death, Russell Westbrook faced the Lakers on his Oklahoma City Thunder’s home court. From the very first moments, it was obvious that Russ was in another gear — which is saying quite a bit, because dude has only one gear and it’s fucking go. He was already a triple-double machine, having averaged one the season before. He was already an indefatigable force of nature, an irresistible tornado. But this was different. Westbrook didn’t show anger, didn’t scream. It’s like he was somehow channeling every bit of his preternatural force through a single, silent conduit. In the first 11 minutes of the game, the man had 10 assists and seven rebounds.

As the game continued, Westbrook began to let loose a little bit, giving out his signature yells and dapping up teammates. It wasn’t clear where he was headed until the fourth quarter, and when he finally got there — snatching his 20th rebound with 40 seconds left in the game — he gave voice to his otherworldly performance. “That’s for Nipsey!” Westbrook roared to the crowd, that familiar vein in his neck echoing their quickened pulse. Twenty points and 21 assists to go along with those rebounds made it the second 20-20-20 triple-double in NBA history (alongside the great Wilt Chamberlain).

That stat line, of course, stood as tribute to the Rollin 60s, Nipsey’s L.A. crew. But Westbrook’s power that night wasn’t just in the numbers—it was also in the emotional release that came with it. It seemed like the league could breathe again.

Admittedly, that relief has been difficult to come by lately. Kobe Bryant’s sudden death earlier this year gave the league and the world another hitch — only to be followed by an even more intense gloom, as we mourn what increasingly feels like a Covid-19-related end to the 2020 season.

It’s sobering now to hearken back to a time when we still had basketball and all the ancillary joys and quirks that make NBA fandom so singularly rewarding. Before March 31, 2019, we might have thought of Nipsey and Lauren London on the sidelines as just one of those little NBA idiosyncrasies: just a couple stars among the constellations of the Staples Center floor-level firmament. But what that day taught us — what the NBA’s overflowing love taught us — is that it’s the small details, the subtle minutiae of the game and those who enjoy it, that bring us the most joy.

“It don’t matter who you are,” Montrezl Harrell would say before skittering out of the arena that night, wearing a fictional hero’s hockey jersey as he commemorated a real one. Tragedy is tragedy, he might add. But it takes a special kind of fan who could compel high-performing, life-hardened athletes to hurt out loud. Nipsey was that kind of special to them. And that absolutely mattered.