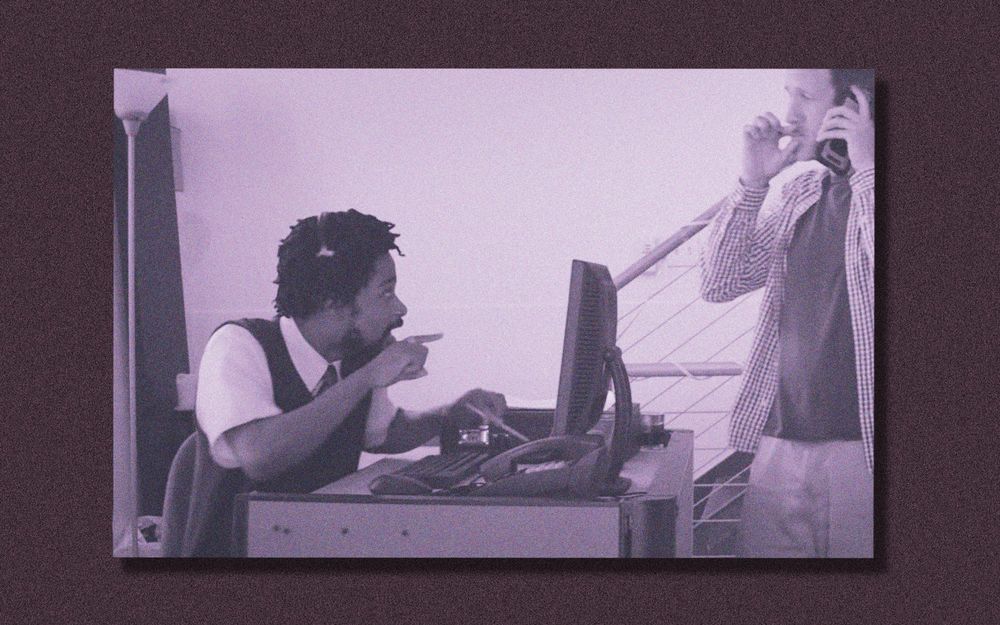

“Sorry to Bother You.” Photo illustration, source: Annapurna Pictures

You never really remember your first time code-switching. It just sort of happens. More like whistling than riding a bike (although, like cycling, once you’ve got it down, you can do it forever). Code-switching is just one of those talents that you subconsciously sharpen until one day, one moment, the opportunity calls for your pitch, diction, and overall energy to take a form of their own, and it just leaps out: your fully formed White voice.

For Black people operating in spheres where Whiteness is the default setting — especially those who deal with paying, borrowing, or procuring money — code-switching is one of the most crucial talents you can possess. (Not to mention dealing with law enforcement, which is its own modus operandi with much higher stakes). It dates back to W.E.B. DuBois’ idea of the double consciousness that’s necessary to survive an oppressive society. And while it’s a relic of problematic respectability politics, smiling and throwing a little extra enunciation into your speech game is one of the few tools at Black folks’ disposal to disarm prejudiced White folks in corporate America.

I started developing my White voice before I even realized it. As a kid, I was always reading, building up my vocab through Black Panther comics or horror fiction like Goosebumps (R.L. Stine, what up!). Back when phone companies would deliver big-ass yellow telephone directories in the mail, I’d even flip through those, perusing neighbors’ addresses and information about local businesses. English classes were a breeze — much to the ire of some of my hating-ass peers — and I’d also taken speech and acting lessons, which furthered my ability to adopt different personas and express myself effectively no matter what room I’m occupying.

When I was old enough to have business of my own to handle, my lingo would convert instinctively, like I’d taken a hit of helium and just finished prepping for the SAT. Half the time, I didn’t even realize I was doing it.

Mom Dukes should’ve known I’d become a code-switching Jedi — because her White voice was immaculate. Every time she’d hop on the phone to discuss billing payments, speak with the teller at the bank, or simply run into one of her White co-workers at the supermarket, her natural dialogue would transform into a cartoonishly pleasant and nonthreatening lilt seasoned with some $10 words plucked straight from T.I.’s thesaurus. It was like flipping a switch for her, and from a young age, I subconsciously picked up on that dichotomy, absorbing it by osmosis. When I was old enough to have business of my own to handle, my lingo would convert instinctively, like I’d taken a hit of helium and just finished prepping for the SAT. Half the time, I didn’t even realize I was doing it.

Back then, I never knew that my country-club-friendly delivery would be the strongest attribute not listed on my LinkedIn profile. Before entering corporate America, I had several client-facing jobs, from selling high-end shoes to a short-lived telemarketing gig (I was like the real-life version of Lakeith Stanfield’s character in Sorry to Bother You, pimping out my White voice for profit and pyramid scheming). A Black man wielding Ginsu-sharp knives has never been less intimidating.

These days, my White voice still helps me move through professional life with tact, managing projects and keeping my team on schedule. Some of my colleagues don’t know how to communicate directly when hiccups arise, and it feels like I have to take extra care to present myself as affably as possible. The shit is annoying — toning down your true, already-amiable self to placate others — but while there’s no clear-cut way to prove it, it’s obvious that it’s helped my career trajectory in a variety of ways, from job interviews to presentations for stakeholders.

Lately, though, I’ve been feeling like it’s time to put a kibosh on my White voice. It’s been a great run, indubitably, but as my career has grown deeper, I’ve felt increasingly conflicted about the professional costume I’ve donned since entry level. Of course, there’s a facade that we all put on at work. But the racism reckoning that’s become one of 2020’s greatest byproducts has found employers finally listening — like, really listening — to their Black and POC employees and putting forth some effort to make workplaces feel inclusive. So why not take them up on that and throw my White voice to the wind in the process?

So, this is it. For at least the remainder of 2020, I’ve decided I’m gonna be my Black-ass self at work. Call it the Shannon Sharpe effect. Or the Don Lemon makeover. That’s not to say that my professionalism goes out the window — I’m still all about producing good work. I’m just saying, these days, I’m not monitoring the bass in my voice when requesting updates on the latest marketing initiative. And $2 words will fare just fine. Let’s just hope my colleagues are ready for all of this real talk.