It was a chilly September night in 1973 at Shea Stadium in Queens, NY when Willie Howard Mays bid farewell to the game in which he devoted so many summers, and to the fans that cheered him on. It was a school night, so my parents allowed my seven-year-old self to stay up late for what was billed as Mays’ retirement ceremony. Unlike many in the stadium that night or tuned into WOR (Channel 9) for the call from Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner, I had no memories of who Mays, The Say Hey Kid, was in his prime. Even that last MVP campaign of 1965, concluded months before I entered the world. Why did this seven-year-old boy need to watch this closing chapter of a 42-year old baseball player, who he knew little about the year before? It had everything to do with the man, the father, whose own view of what was possible in the world for his son, was linked to a generation of Black baseball players who made those dreams possible.

Other than counting money in the dark, Baseball was the best measure of how my dad’s mind worked: intricate, nuanced, attention to small details (like that feathery fluttery thing that his favorite singer Sam Cooke used to do), thoughtful. The woman he loved and was married to for just short of 45 years was pure bombast; Baseball was one of my dad’s reprieves.

I was introduced to the game during the 1971 World Series. My mother, who was raised in Baltimore, and my father “wagered” on the Orioles and the Pittsburgh Pirates, who are still the Blackest baseball team ever. I was hooked watching Steve Blass, Willie Stargell and of course the great Roberto Clemente, who finally had a national audience for his spectacular, but diminishing skills.

I was born and raised in the South Bronx, and we lived a short bus ride from Yankee Stadium. The first games that I attended may have been in the “House that Ruth Built” but I was never gonna be a Yankee fan. My father was of a generation in which the National League and American League were partisan choices, especially after that Designated Hitter rule was implemented in the so-called Junior Circuit. That my father was a teen when Jackie Robinson broke in with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, meant his allegiance to the National League was cemented.

Related: You Should Have Known Josh Gibson Before Major League Baseball Included His Stats

Those were sparse years for the Yankees, and if not for Horace Clark and Roy White, I would have likely never seen the insides of Yankee Stadium; my dad was a National Leaguer and a Race Man. In terms of colors though, my dad’s were Orange and Blue; the Orange borrowed from the New York Giants and the Blue from the Brooklyn Dodgers, the two National League teams which departed New York City for the West Coast after the 1957 season. Needing a National League franchise in New York City, the laughable and lovable Mets were born in 1962. My dad became a Mets fan; I became a Mets fan.

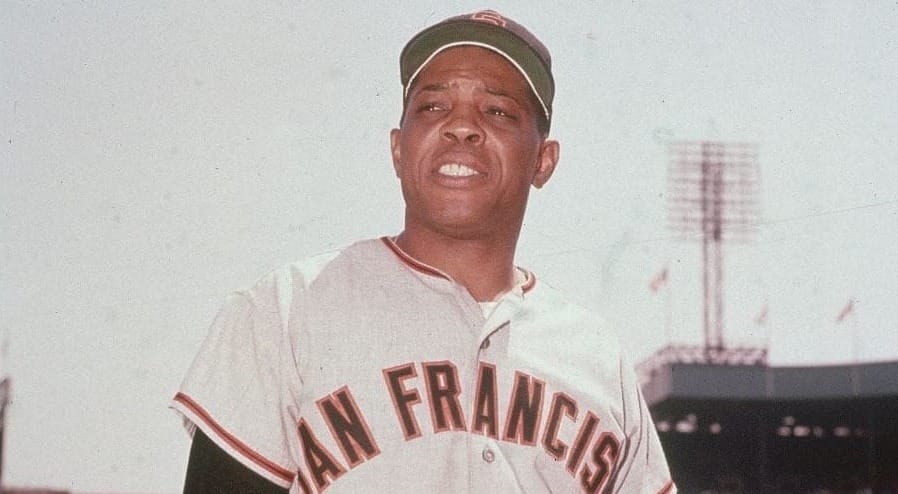

My dad and I had begun our Sunday routine of Met games on TV—a good Sunday if Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman or Jon Matlack were taking the mound—when my father’s own baseball hero, Willie Mays, was traded to the Mets from the San Francisco Giants in May of 1972. The Giants were the franchise that made Mays a national star, first in New York, Harlem really, and then in San Francisco. The Giants moved to San Francisco two years before my father arrived in New York City from Thompson, Georgia, so Mays’ trade to the Mets felt like a homecoming of sorts for my dad. It was as if we were, for the time we watched those games, sharing in a boyhood.

At least once a year my father and I made the three-train trek out to Queens (The Third Ave El, the 2 Train and the garishly colored 7 train) to see the Mets. We were in Shea stadium on July 8th of 1973 when Hank Aaron, in his dramatic chase of 714, hit two homers against the Mets, and it was the only time I got to see Mays (or Aaron) play in-person.

Like most baseball fans, my father was drawn to the swing-and-miss strikeout and the big homeruns. Mays hit 660 homeruns, but only 14 of them in his two seasons with the Mets. But for my dad it was the small things: executing a perfect-bunt, the exquisite hit-and-run play, and the pitcher with pinpoint control who could “paint the corners’’ of the strike-zone. My dad was never on-the-nose about those things. The big message was that with effort and even talent, life was a game of nuance and mishaps.

Baseball, like life, is mostly a game of failure. The best batters often fail 70% of the time, making it a game in which failure is a feature and not a bug. For my dad, teaching his son not simply how to play the game, but the strategy behind it, became his way of sharing with me the failure embedded in Black fatherhood, Black manhood, and success itself.

I was a toddler when the Mets won the World Series in 1969, though my dad, regaled the exploits of Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee, two Alabaman born Black men, for years, long after that championship season. But it was the 1973 World Series, which the Mets lost in seven games to the mighty Oakland Athletics (A’s), that captures so much of what my father taught me about life through baseball.

In the tenth inning of game 2, the longest ever in the history of the World Series, clocking in at over four hours, the home plate umpire called the Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson out at home plate. Dad leapt from his chair angrily like he was gonna jump through the screen to argue with the umpire. The call was bad, the catcher missed the tag, and everyone could see it, including Mays, who raced to home plate and engaged the umpire before he dropped to his knees begging the official to reconsider the call.

The Say Hey Kid, a player who inspired generations of American fans with how he roamed centerfield like a field general, and ran the basepaths with controlled abandon, his cap, purposely a size or two too small, flying off his head, was gone. Another player, a lesser one at forty-two years old, in the prone position, petitioning, had shrunk into the young hero’s place. This was certainly not the ballplayer that my father so often celebrated (I never saw that player except in old television footage.). I am sure that it was painful for my father to watch his diminishment in real time, on our first color TV, no less.

My dad, who was only four years younger than Mays, may have felt well past his prime also. Yet while Mays’ prime was one that Black Americans applauded, my dad might have known that there would never be a prime that even his family, and perhaps most importantly, his son, could ever applaud.

Earlier, in that same World Series game, Mays badly misplayed a fly-ball in centerfield, stumbling to the ground, the clearest evidence that his body was beginning to betray him. Indeed, my dad had already metaphorically stumbled more times than I could possibly know, even now, and his own body would betray him several times before his death. Mays was our Centerfielder and he lay face-planted into the grass of Oakland’s Alameda Stadium.

That game was the last game that Mays played in his storied career. I imagine he was exhausted after that game; I was exhausted watching, in what seemed like an endless afternoon at a time when World Series games were still broadcast during the day. I was barely hanging on when Mays hit the “Baltimore chop” in the 12th inning that proved to be the game winner.

Related: Why Jackie Robinson's Impact Still Hits in a League Light on Black Stars

That memory of game 2 has stayed vividly with me for more than 50 years. My dad and I never talked about that last moment of Mays’ on-the-field greatness; it was not our way. And that was the last World Series the Mets appeared in for another 13 years. Mays’ time with the Mets was a blip, like Michael Jordan’s time with the Washington Wizards or Emmitt Smith’s days in an Arizona Cardinals uniform. Yet it’s the Willie Mays that most matters to me, because it is the Mays that made my father most endearing to me.

As the news spread of Mays’ death — Keith Hernandez and Gary Cohen were near tears during the Mets broadcast that I was watching — my first inclination was to call my dad. It is an urging I rarely had during the last years of his life, and certainly not in the 16 years since his death. Hopefully, wherever his spirit resides, my father felt that impulse. Willie Mays, our Center Fielder, had left the field for the very last time and I wanted to thank my father for allowing me to experience with him those last glimpses of Mays’ greatness…and his own.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.Our Center Fielder Has Left the Field for the Last Time: on Willie Mays

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.