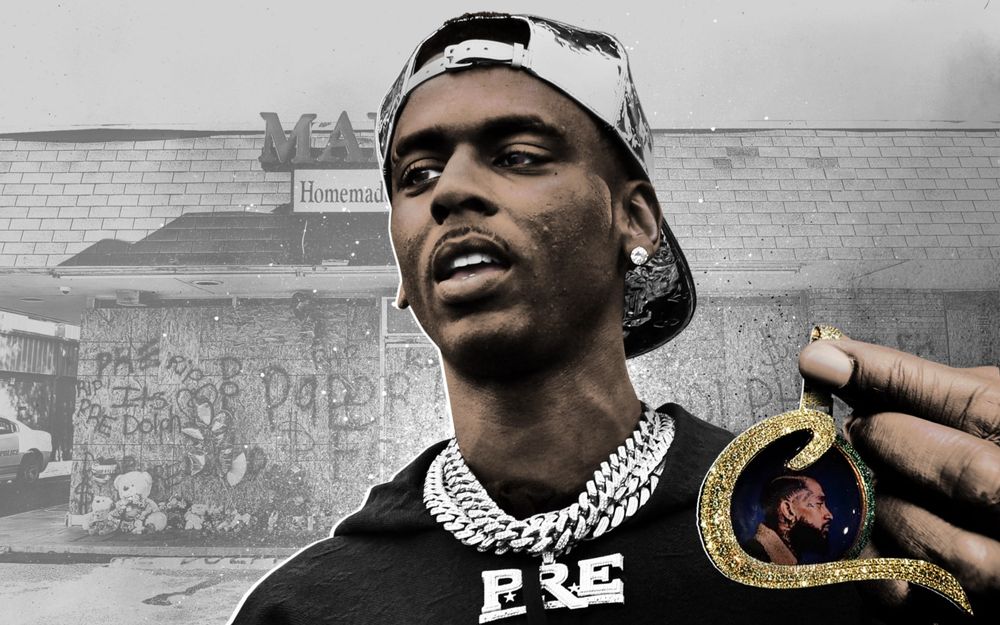

"Happy C-Day, Neighborhood Nip,” said Young Dolph in a clip posted to Instagram in August, on what should’ve been Nipsey Hussle’s 36th birthday. “R.I.P. my boy. Real niggas still miss you down here, bruh.”

Dolph drove the point home by showing off a brand-new custom chain, a sequence of chunky bedazzled links attached to an iconic portrait of the dearly beloved rap mogul, set against a field of deep blue, surrounded by an iced-out Crenshaw C.

Exactly five years prior, Hussle had celebrated his 31st birthday with the release of Slauson Boy 2, the last commercially available mixtape of his career. “Really came up in the field,” Nip proclaims at the top of track 13, on which he’s joined by Dolph and Bino Rideaux. “Get money, get life, or get killed.” The song hits different today, after Dolph lost his life in a brazen daylight shooting, caught in the act of giving back to the people of his city — much the same way Hussle lost his life two-and-a-half years ago. “I ain’t been doin’ nothin’ but count paper,” Dolph rhymes on his verse. “Duckin’ and dodgin’ these haters.”

Adolphus Thornton Jr. was 36 years old, a devoted father to his young son Tre and younger daughter Aria. In May 2020, his children’s mother, entrepreneur Mia Jaye, lost her brother — a devout Christian who ran his own car business — to violent crime. The tragedy inspired her to start a campaign this August called “Black Men Deserve to Grow Old,” highlighting the fact that Black men are 20 times more likely to die of gun violence than White men. Little did she know, three months later her children’s father would become another victim of intraracial violence. Soon after, she shared her pain via IG stories. “God give me strength,” Mia wrote. “Question is: How am I going to tell my babies that daddy is never coming home?”

“When I think about Dolph, I understand him being an ascended master. He tapped into such a level of understanding. He did exactly what he came to do.”

Ermias Asghedom was just 33 when he was taken from this life, leaving behind a young daughter, a younger son, and a loving partner. The parallels between his life and Dolph’s do not stop there. Both were born under the zodiac sign of Leo, in August 1985, just four days apart. Both happened to attend schools named Hamilton High in their respective cities, Los Angeles and Memphis. More than that, they were like-minded individuals who preferred demonstration to conversation.

Hussle and Dolph became self-made millionaires who got it “straight out the mud,” leveraging their musical gifts and hustling ability to create a mighty engine of self-empowerment. Both progressed from illicit transactions to audio entrepreneurship. Both were stubbornly committed to resisting the traps and snares of a predatory music industry and building independent movements that allowed them to employ their friends and family while giving back to the communities that raised them. And now both men will be memorialized with streets named in their honor.

+

Like Hussle, Dolph understood the hustler’s credo that “hate come with the plate,” as Bay Area mogul E-40 so memorably put it. Dolph knew the risks of spending time in Memphis all too well, but he never considered turning his back on the people of his city and especially his old Castalia Heights stomping grounds.

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, it’s easy to second-guess now. Why was Hussle in the parking lot at Crenshaw and Slauson without security on March 31, 2019? What was Dolph doing back in his hometown where he knew there were people who had issues with him since he dropped his 2016 album King of Memphis? Neither of these kings walked in fear. They had more than enough money to stay far away, but they kept close enough to touch.

Dolph made a choice not to live in a gilded cage, spending as much time as he could in Memphis with his mother and extended family. His aunt Rita had been battling cancer but still helped out with his holiday program, buying Christmas presents for children in the community. Dolph hosted a turkey dinner giveaway at the West Cancer Clinic last month to meet the staff that was caring for his aunt. He moved by himself, drove around freely, popping in and out of local stores. “Dolph was everywhere,” one Memphis resident said during an Instagram Live session following the hometown hero’s death. “We would see him standing in line at the post office.” Like Neighborhood Nip, he felt the love everywhere — even as he understood there was a target on his back.

On the afternoon of November 17, Dolph was driving his camouflage Corvette Stingray. He stopped off at a Marathon gas station just down the road from Makeda’s Homemade Butter Cookies. As he filled his tank, another motorist captured a video of the local celebrity pumping gas and posted it on social media. Before making his way to one of his annual Thanksgiving turkey giveaways, Dolph stopped off at the shop on Airways Boulevard to pick up some chocolate chip cookies, hot and fresh from the oven, just the way he liked them.

While he was inside, a white Mercedes two-door pulled up at the cookie shop. Two young men wearing Covid masks hopped out and dashed across the parking lot, one gripping a semi-automatic pistol, the other an AK-47 draco. Shots rang out and plate glass shattered along with the dreams of a young legend, and his family, and his community.

+

The first time I met Young Dolph, he was hosting a lavish banquet at the Asian fusion restaurant Buddakan in New York City’s Meatpacking District. He sat at the head of a long table, accompanied by his Paper Route Empire partners Jeremel “Daddyo” Moore and Nakia Hicks, as well as his cousin, the rising star Key Glock. The platters of seafood and roasted meat and vegetables kept coming as did the well-wishers, a who’s who of hip-hop media — DJs, writers, editors — gathered for the occasion. Rick Ross stopped by late in the evening to pay his respects; the two bosses stepped to the side to politic in private.

“Man, it’s another legend lost too soon,” Ross said in a video tribute to Dolph, showing off the PRE chain Dolph gave him. “It was priceless when he give it to me, but it’s more valuable than ever.”

I had an extended conversation with Dolph in May 2017, just a few months after his car was ambushed in Charlotte while he was en route to a show. As legend has it, 100 shots were fired at Dolph’s bulletproof vehicle and he lived to tell the tale. (Police reported that several dozen shell casings were found at the scene.) He may have been expecting trouble. Just a few days prior, Dolph had released a video for “Play Wit Yo Bitch,” a vicious diss track aimed at Yo Gotti, another Memphis rap mogul who had tried to sign him. When Dolph declined, as the song says, “you went from my biggest fan to my biggest hater.”

This brush with death apparently left Dolph unfazed, as he soon doubled down on the defiant bars. “How the fuck you miss a whole hundred shots?” he asks on his single “100 Shots,” which went on to be certified gold by the RIAA. The accompanying album, Bulletproof, reached the Top 40 on Billboard’s album chart. If success is the best revenge, Dolph was getting plenty of it.

+

Still, I wasn’t sure what to expect when we sat down for a face-to-face interview at Mass Appeal’s Manhattan office. The man had been through a lot since we’d first met at that dinner, and it was my job to talk about everything. But Dolph couldn’t have been more relaxed, calmly sipping his tea as he fielded my questions.

“For people to deal with they problems in life,” Dolph told me in his deep Memphis drawl, “you just gotta face that shit and really deal with the facts and eat that shit up and go with that shit like with war. If you gon’ run from that shit and hide from that shit and be mad about the situation, it’s gonna be a problem you gon’ always have your whole life.”

We spoke about his early childhood on Chicago’s Southside, and how his grandmother took the boy she called “Man Man” to Memphis at age two when his mom and dad couldn’t care for him. “I had a problem with my parents when I was younger just because I just felt like, ‘Aw shit, they don’t give a fuck about us,’” Dolph admitted to me. But once he saw the impact of drug addiction and alcoholism for himself, he began to better understand the situation. “My mama told me I was a star though,” he added with a smile.

We talked about how he survived by hustling in the streets of Memphis until his homeboys encouraged him to take rap seriously. “If shit make sense to me, I’ma play with that shit,” he said. “And if I give anything my attention, I’ma master that shit.”

Soon enough, he made his first song. Then, his first mixtape, Paper Route Campaign, in 2008. Persistence paid off as he watched his music spread like the measles. “It started from, ‘I’m finna show my boys,’” he recalled. “To, ‘Damn, the hood they love it.’ To, ‘Damn we got the whole city on this shit!’ To, ‘Damn, bruh, we got the whole state! Down there in Mississippi on this shit, down there in Alabama, down there in Carolina!’” It was a feeling he couldn’t explain, especially considering that he’d done it by himself. By 2015, he was making enough money to get arrested for driving around in a new Rolls Royce with no tags, an incident he detailed on his Shittin on the Industry mixtape. That same year, he guested on O.T. Genasis’ double-platinum smash “Cut It.”

When we got to talking about the shooting in Charlotte, Dolph took his time, speaking in a slightly softer voice and choosing his words carefully. “Charlotte really was crazy,” he told me. “To date, that probably was the biggest test of my life.” He was proud of the fact that he’d still made it on the stage that day, performing at four shows during the CIAA basketball tournament weekend. “My fans, they was there,” he said. “They paid they money, know what I’m sayin’? It is what it is. And that’s what I was in the city for.”

I asked Dolph if he was surprised that his vehicle was shot up. “I was surprised but I wasn’t surprised, if that makes sense,” he said. Was he scared? Could he hear and see what was going on? “Shit, it’s shots,” he replied. “You can’t do nothin’ but hear it. And you see it, cause the light, it’s… you know. It is what it is.”

This wasn’t the first time Dolph had been in a dangerous situation. “On my mama,” he told me, “that’s the shit that everybody know about. It’s like three of these same incidents where I be like, ‘Damn I’m ’posed to die now.’ Damn, this shit crazy. That’s God.”

I let that sink in and expressed my genuine concern for his well-being. “I ain’t worried at all,” Dolph stated matter of factly. “Reason number one, I’m good with God. Second, I know what kinda person I am. I know what I’m doin’. I know how I’m movin’. And I’m straight. I’m doin’ too good to be worried about anything. I’ma let the people who’s stressed out and mad and got problems and shit be worried.”

Just hearing him talk this way had me stressed out. “It’s like this, dog: I ain’t trippin’,” Dolph went on. “If I ain’t trippin’, I don’t need nobody else to be trippin’. Know I’m sayin’? Cause I’m laughin’ at that shit. End of the day, I win, they lose. Point-blank period.”

Four months later, Dolph bumped into some people from Memphis in the valet parking area of a Hollywood hotel. They got into an argument, which escalated to the point where Dolph was shot multiple times and rushed to the hospital in critical condition. An arrest was made, but the suspect was released with no charges filed. For his part, Dolph said he “had no clue” who shot him. The following year, Dolph released an EP titled Niggas Get Shot Everyday, proudly displaying his surgical scars on the accompanying artwork, surrounded by a lavish fur coat and excessive amounts of gold and platinum chains.

“I always gamble big, and I always gamble on myself. I’ma gamble big as a motherfucker. Like, I don’t give a damn. Cause I don’t ’posed to be here. How I look at that shit. I don’t ’posed to be here.” —Young Dolph, 2018

In early 2020, Dolph hinted at retirement from the rap game. “Highly considering quitting the music business because I really wanna be with my kids 24/7,” Dolph posted on social media. Like the rest of us, he spent much of the year quarantining, but especially enjoyed spending quality time with both of his children. “I’m in my daughter’s room, I’m in her little castle thing she got,” he told GQ in an interview published last May. “She crawl in, I’m crawling my big ass in that motherfucker. I’m in their world right now.”

According to filmmaker and podcaster Tim Jackson, Dolph made sure his kids would see more than just miniature homes in the future. He’d reportedly owned more than 100 properties in Memphis, and made a yearly tradition of purchasing foreclosed homes for his children’s birthdays.

In March of 2021, as Dolph and his cousin Key Glock — who by that point was a millionaire in his own right — released Dum and Dummer 2, he flirted with the idea of retirement once again, citing other business opportunities in a conversation for DJ Scream’s Big Facts podcast in July. A deluge of outraged DMs and text messages compelled him to reconsider.

“I can’t quit doin’ music,” Dolph explained, touting his Paper Route Empire label as a proof of concept for indie artists who bet on themselves. “It’s like I’m the spokesperson for all of the street niggas and all of the niggas that’s on some independent shit… I can’t let them folks down. It’s like I’m their motivator.”

“I ain’t gonna lie and say I ain’t thought about [signing with a major label], cause I was this close to doin’ that shit,” he continued. “But I always go back to my mentality. It just ain’t just you no more. You done turnt niggas into millionaires. How many niggas can say ‘I done turnt other rappers into millionaires without using a major label’?”

In many ways, Dolph and Nipsey Hussle were running the same Marathon. They were in it to win by all means necessary, and they wanted to see their people in the winner’s circle with them. Still, as I wrote in my book about Nipsey, “the Marathon is not a team sport. You can get support from your crew and train together, but nobody else can run those laps for you. Even in a crowded field, the long-distance runner goes it alone, testing their character and spirit as much as their physical limits, pushing for a personal best, competing against themselves and the clock. Tick-tick-tick.”

Rap is a competitive sport, and there’s no rule that says you have to share your special sauce with others who want to sprint in your sneakers or knock you off the throne. “Niggas wanna keep shit a secret,” Dolph told DJ Scream. “I ain’t never been a secret-ass nigga. Helpin’ niggas get some money or seein’ niggas come up. I just like to see niggas ball.”

Among the Cali artists who paid tribute to Dolph after his death was J Stone, one of Hussle’s closest associates on the All Money In team. “Damn 🙏🏾 R.I.P @youngdolph you was a big inspiration and I can honestly say you fucced wit me,” Stone posted. “Rest well Bruh we made great music together.” Grape Street legend 03 Greedo, who is currently serving a lengthy sentence on drug and weapons charges, paid his respects to Dolph from behind bars. “The last call I got on that plane to turn myself in was from you,” Greedo wrote. “Right after Nip n y’all both gone. It hurts to lose the niggas who helped me make my first million.” Greedo also credited Dolph for teaching him about publishing and keeping his circle of associates as tight as possible.

Hussle could’ve been speaking about Dolph on the Victory Lap cut “Loaded Bases,” when he spoke about his motivation, the testimony of a man of great ambition who’d grown accustomed to risking everything every single day. “See it’s a couple niggas every generation that wasn’t supposed to make it out, but decode the matrix,” Hussle rapped. “And when they get to speak it’s like a coded language. Reminds niggas of they strength and all the stolen greatness.”

“Man, it’s like the only thing we can really leave behind is culture, is music,” Dolph said when I interviewed him for the 2018 documentary Dirt to Diamonds. “And dignity and determination. That’s what we have.” At the time, he had just turned down a $22 million offer from a major label.

“It take money to make money,” Dolph said. “I always gamble big, and I always gamble on myself. I’ma gamble big as a motherfucker. Like, I don’t give a damn. Cause I don’t ’posed to be here. How I look at that shit. I don’t ’posed to be here.”

As the shock of Dolph’s senseless killing begins to sink in, people’s minds have begun turning to the unanswerable question of “Why?” The highly publicized rivalry that divided the Memphis rap scene was ultimately about more than just rap beef. The roots of the conflict went back to the question of maintaining independence and control over one’s intellectual property.

Just as Hussle had resisted offers to sign away his rights and insisted on the autonomy of his family-owned label, All Money In No Money Out, Dolph stood firm behind his Paper Route Empire imprint, rejecting offers to sign with a local label with major backing, even when bruised egos led to brutal diss tracks and threats of violence. Through it all, Dolph and his PRE team still managed to rack up billions of streams, Billboard hits, and RIAA plaques.

“Another strong-minded king gone too soon,” lamented producer Bink! on his social media accounts. “Why is it that all of the artist that show you that being independent is the way GET MURDERED? Things that make you go hmmmm…”

A full-blown artists’ rights movement is now unfolding within the music business, fueled by a wave of new technology that falls under the banner of Web 3.0 and the blockchain. New music NFT platforms like EQ.Exchange are emerging, with the stated goal of empowering artists and the fans who support them to come together and “fuck the middleman” in much the same way that Nipsey Hussle’s groundbreaking Proud 2 Pay campaign first did back in 2013. Just two months ago, Dolph tweeted about exploring NFTs.

“I’ve known Dolph since I was a kid,” Key Glock told me when we spoke in 2018. “I’m his cousin by marriage but that’s really my brother.” He was already rapping before getting down with PRE, recording his own songs since ninth grade. But Dolph and Daddyo helped Glock level up. “Look at me now,” he said with pride. “Self-made.”

+

“Dolph was so proud of Glock,” says PRE’s in-house communications officer Nakia Hicks, who’s going through her own profound mourning process. “He held him so precious.”

On November 23, Key Glock put up his first post following the tragedy, a selection of photos of the two of them over the years. “Damn bro, I’m lost,” Glock wrote in his caption, sharing the overwhelming pain of losing Dolph as well as his father, his aunt, and his grandmother in recent times. “You was Phil Jackson and I was your MJ,” he added, pledging his allegiance with the hashtag #PaperRoute4Life.

Reading his words, I thought about my conversation with Glock three years ago. He was trying to explain why he loved Memphis so much. “The city of Memphis taught me everything I know,” he said, “loyalty, trust, respect, love.” When I asked about the hard times he’d seen in the city, the smile never left his face. “You gon’ go through all the negatives in those stages in Memphis,” he said. “Before you get to your best peak, you gon’ go through hell four, five times. The hardest thing I had to go through being in high school was losing homies back-to-back through gang and gun play. It wasn’t never no car wreck or nothin’. It was always something we was into.”

That’s what makes this loss even harder: the fact that Dolph and Glock were all about getting away from negative bullshit.

“They never said no to anything when it came to giving and taking care of people. That’s all they ever cared about, Daddyo and Dolph — giving and taking care of people.”

As of late November, there have been nearly 300 homicides in Memphis in 2021, indicating a rate set to surpass the figure that made 2020 the city’s deadliest year ever. (The U.S. saw its largest surge of homicides in modern history during 2020, and the horrific trend shows no signs of slowing.) Memphis is an open-carry state dealing with a legacy of generational poverty and racial segregation, issues that are compounded by the stress of a pandemic, economic pressure, and the tensions rippling across America, from George Floyd to Kyle Rittenhouse. In short, the city is a powder keg. Soon after the white Benz used in Dolph’s murder was discovered by police and taken in for forensic investigation, the neighbor suspected of tipping off the cops was murdered.

“You’re not going to stop the violence without addressing poverty,” said Shelby County Commissioner Van Turner during a virtual town hall meeting organized by the NAACP in the wake of Dolph’s murder. “We’re not going to stop the violence without addressing mental health, which is a part of poverty.”

Tameka Greer, founder of the community organization Memphis Artists for Change, stressed the importance of helping incarcerated persons transition back into society after being released. “We got to find those individuals who have been through some things in their personal lives,” said Memphis resident Anthony Sledge. “See, if you’ve never been hungry you can’t tell nobody about being hungry.”

Dolph’s death did not stop the Thanksgiving turkey giveaway, which went on with a vengeance in his honor. A public memorial service is set to take place on Thursday at FedEx Arena in Memphis; the free event reportedly sold out in under two hours. His fans, after all, need a chance to mourn, too.

“Dolph was very different,” says Nakia Hicks. “He was such a good-hearted person. I just wish more people had the chance to know that person.”

Hicks cherishes the memory of moments like the time during the pandemic when Dolph picked up his grandmother in Chicago on a private jet. “He was just so proud that she was in the jet with him,” Hicks remembers. “You have no idea the familial bonds.” But he treated the whole city like family. “For Christmas, we had three stops — two women and children’s centers and one senior center,” she says. “Daddyo and Dolph gave Aunt Rita $50,000 to buy gifts. And I said to Daddyo last week, ‘We’re gonna need more money.’”

“Aw, it’s all good,” Hicks remembers Daddyo replying. “Just let me know.”

“It was always all good when it came to giving to people and caring for people,” she adds. “They never said no to anything when it came to giving and taking care of people. That’s all they ever cared about, Daddyo and Dolph — giving and taking care of people.”

While dealing with the death of another close friend, Hicks read about the concept of the ascended master.

“It’s like when you reach a level of understanding and consciousness,” she explains. “When you tap into a certain level of being, then you can go. It’s rooted in the Buddhist idea of reincarnation. You come to figure out lessons and you keep reincarnating until you figure out the lessons. They say that Bruce Lee was an ascended master. And with Nipsey when he died. He’d come and gotten the information and was able to share the information and was able to exist in the space. And so when I think about Dolph, I understand him being an ascended master. He tapped into such a level of understanding. He did exactly what he came to do.”

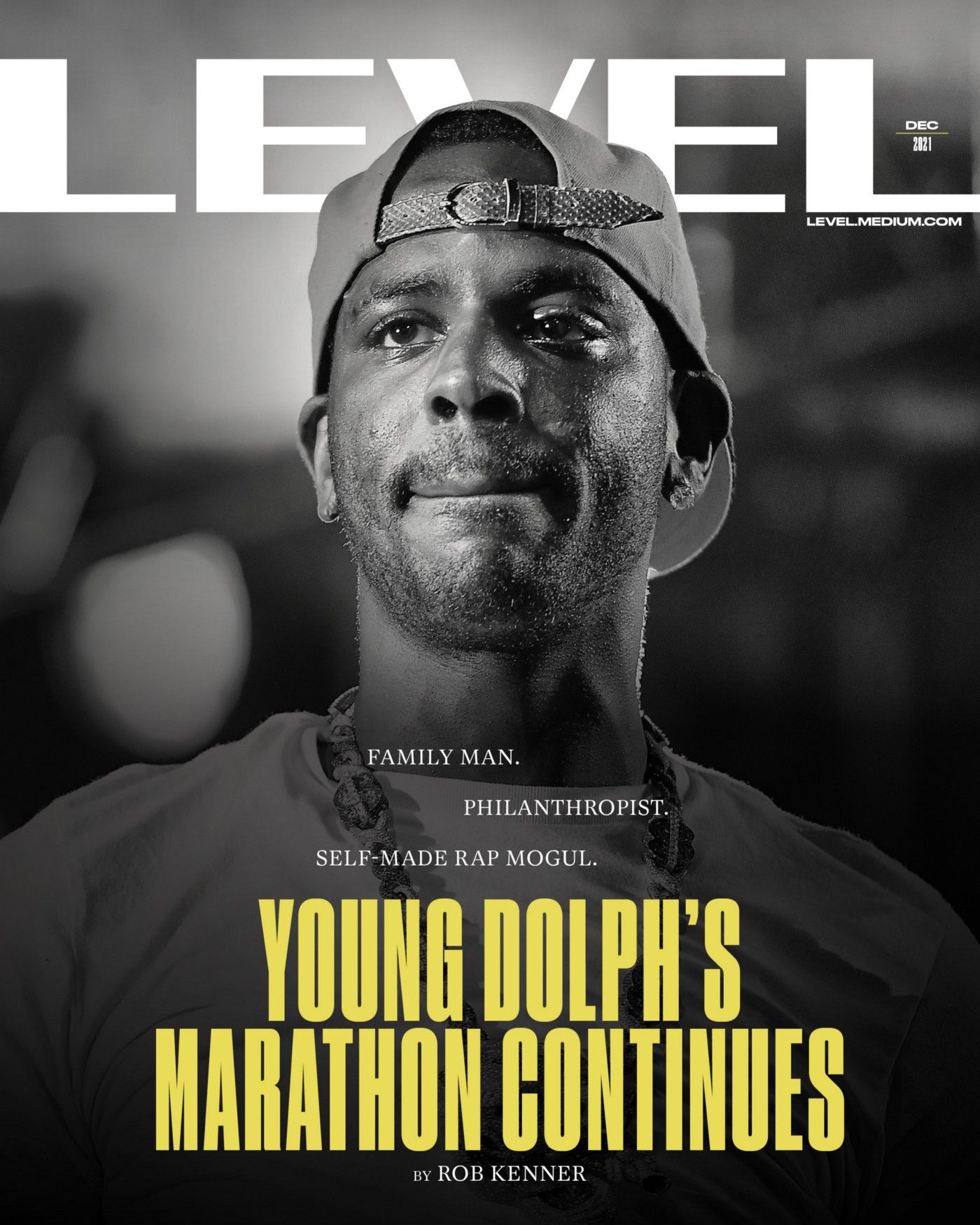

To kill the man is to release the myth. Even in death, Dolph’s name and his Paper Route will carry on, just as Hussle’s Marathon continues. Dolph’s face is already painted in the Memphis airport. And for anyone who was ever offended by the king of Memphis conversation, now there is no need for any of that. Now there is no conversation to be had.

Rob Kenner is the author of The Marathon Don’t Stop: The Life and Times of Nipsey Hussle.